Translate this page into:

Association between intimate partner violence & HIV/AIDS: Exploring the pathways in Indian context

Reprint requests: Dr. Seema Patrikar, Department of Community Medicine, Armed Forces Medical College, Ministry of Defence, Pune 411 040, Maharashtra, India e-mail: seemapatrikar@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Violence against women cutting across diverse socio-economic classes is an under-recognized human rights violation in the world. This analysis was undertaken to examine the prevalence along with predictors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and its association with HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Indian ever-married women.

Methods:

The data obtained from 2005 to 2006 third round of National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3) were used in this study. Analyses were conducted on ever-married women by linking individual women data including violence information and HIV test results.

Results:

The analyses indicated all forms of violence to be prevalent in India. The prevalence of lifetime IPV reported was 35.3 per cent. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression identified younger age of women, higher number of children, low level of education of women as well as her partner, working status of women, higher spousal age, rural residence, alcohol consumption by husband, childhood witness of violence among parents, nuclear household and lower standard of living to be positively associated with the experience of IPV by the women (P<0.05). HIV-positive status of women, as well as women from high HIV prevalent State, were at increased odds of IPV (P<0.05).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Significantly higher reporting of HIV/STIs by women experiencing IPV hints at new pathways that link violence and HIV. Further, our analysis showed a high prevalence of IPV in India.

Keywords

HIV/AIDS

human immunodeficiency virus

predictors

variance inflation factor

violence against women

Violence against women cutting across diverse socio-economic classes is an under-recognized human rights violation in the world1. The data from the worldwide literature suggest that intimate partner violence (IPV) is almost a universal phenomenon existing in all communities2. The prevalence of both physical and sexual violence against women within marriage has been increasingly documented in India, but information regarding its correlates and health consequences are scant. There are a several factors that complicate the issue in India, as in other countries such as lack and denial of access to economic, political and social resources, vulnerability to indigenous oppressive institutions of caste, religion, traditional family structures, non-democratic political structures and dowry system. Studies conducted in India suggest that about 50 per cent of women experienced at least one of the violent behaviours at least once in their married life34. Preventing violence against women is considered as a way to contribute to achieving the millennium development goals (MDGs)5. As noted by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to prevent violence against women, it is crucial to understand the circumstances, and the risk and protective factors that influence its occurrence6.

Violence can have direct consequences for women's health and can increase woman's risk of future ill health. Documented effects include delayed prenatal care, inadequate weight gain, increased smoking and substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), vaginal and cervical infections, kidney infections, miscarriages and abortions7, premature labour, foetal distress and bleeding during pregnancy8. The literature emphasizes the linkages between the experience of IPV and both fatal and nonfatal outcomes for women and their children91011. Increased prevalence of STI/HIV may reflect greater likelihood of STI/HIV exposure in abused women, rendering IPV a risk marker for their male partners’ STI/HIV infection.

This study was, therefore, undertaken to provide a comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of different forms of violence in ever married Indian women and its associated risk factors with emphasis to linkage with HIV. The primary objective was to estimate the prevalence of IPV in terms of physical, sexual and emotional violence in ever married Indian women and to identify various predictors of IPV. The secondary objective was to determine the association between IPV and proportion of HIV/AIDS and self-reported STIs.

Material & Methods

For this study the data obtained from 2005 to 2006 third round of National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3)12, a representative sample of households throughout India, were used. Data on 69,704 ever married women who were interviewed for IPV taking precautions, in keeping with the World Health Organization's ethical and safety recommendations for research on IPV11, were analysed. For these analyses, only ever married women were included since the outcome of interest is lifetime IPV experience. NFHS-3 tested 102,946 men and women for HIV of whom 52,855 were women. Of the total number of women tested for HIV, 57 per cent (n=30,033) were interviewed for IPV module. The two files were then merged.

The NFHS-3 volume 113 reports that the baseline characteristics such as age, residential, educational, religious, caste/tribe and wealth index distributions of the subsample of women who completed the IPV module and HIV testing were virtually identical to the entire NFHS-3 sample of eligible women, hence baseline characteristics were not tested. The key dependent variables of interest in this analysis were lifetime experience of various forms of violence. Ever-married women were asked a series of questions on the experience of physical, emotional and sexual violence based on a modified version of the revised Conflict Tactics Scale14. A ‘yes’ response to one or more of items (a) to (g) in the appendix constitutes evidence of physical violence, while a ‘yes’ response to items (h) or (i) constitutes evidence of emotional violence and a ‘yes’ response to items (j) or (l) constitutes evidence of sexual violence. A dichotomous variable IPV was constituted as evidence of IPV if the women experienced either of physical and/or sexual and/or emotional violence.

The various correlates or predictor variables considered were women's characteristics, husband's characteristics, union characteristics and intergenerational effect in terms of violence in childhood. These variables were drawn from literature on women's experience of IPV1516. The presence of HIV and self-reported presence of STIs was also recorded. In the NFHS-3 survey all women who ever had sexual intercourse were asked whether they had sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), genital sore/ulcer and vaginal discharge in the past 12 months. The HIV status of the women in IPV module of NFHS-3 was determined by linking and merging the IPV data with HIV data for each women of NFHS-3.

Statistical analysis: The prevalence of various forms of violence is described with 95 per cent confidence interval (CI), and the associations are expressed in terms of odds ratio (OR). Multivariate analysis using logistic regression was adopted to predict IPV as well as other types of violence. As the prevalence of HIV/AIDS was high in six States namely- Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Manipur, Nagaland, and Tamil Nadu and moderate/low in other States, the regression models were adjusted for the prevalence of the States in predicting IPV. Results are shown in terms of OR with OR of >1 implying risk factor and <1 as protective factor. Four logistic regression models were run with the outcome variable as physical, sexual or emotional violence alone as well as for physical and/or sexual and/or emotional violence. Multicollinearity in the variables predicting violence was detected by tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF). VIFs exceeding four was considered as a sign of multicollinearity requiring correction17. The model was rerun after testing for multicollinearity. All these analyses were carried out using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) at 0.05 level of significance.

Results

The socio-demographic variables are depicted in Table I. Table II gives the experience of violence by ever-married Indian women along with 95 per cent CI. The analysis of ever-married women revealed that 35.3 per cent (24,394) women respondents experienced IPV with 95 per cent CI of 34.80-35.51.

The results of multivariate analysis using logistic regression are given in Table III. The analysis showed four models to predict the dependent outcome variable based on independent predictors. Age at first marriage was removed from the analysis as it indicated strong collinearity with marital duration.

Physical and/or emotional and/or sexual violence: Younger age of women, higher number of children, low level of education of women as well as her partner, working status of women increased the odds of experiencing IPV by women (Table III). In addition, higher spousal age, rural residence, nuclear household and lower standard of living were positively associated with the experience of IPV by the women (P<0.05). Women whose husbands did not consume alcohol did not experience IPV. Women who witnessed their father beat their mother were also at higher risk of experiencing violence. HIV-positive status of women as well as women from high HIV prevalent State are at increased odds of IPV (P<0.05).

Physical violence only: The correlates associated with women experiencing physical violence were similar to IPV except HIV status of women. HIV-positive status of women was not found to be associated with physical violence, however, analysis showed that women from high HIV prevalent State were at increased odds of physical violence (P<0.05).

Emotional violence only: The results were similar to physical violence except that residence and household structure were not associated with women experiencing emotional violence (Table III).

Sexual violence only: All the correlates considered in the analysis were significant in predicting sexual violence except residence, household structure and husband's education level (Table III). HIV-positive status of women, as well as women from high HIV prevalent States, showed strong association with women experiencing sexual violence with increased odds of 1.71 and 2.42, respectively (P<0.05) (Table III).

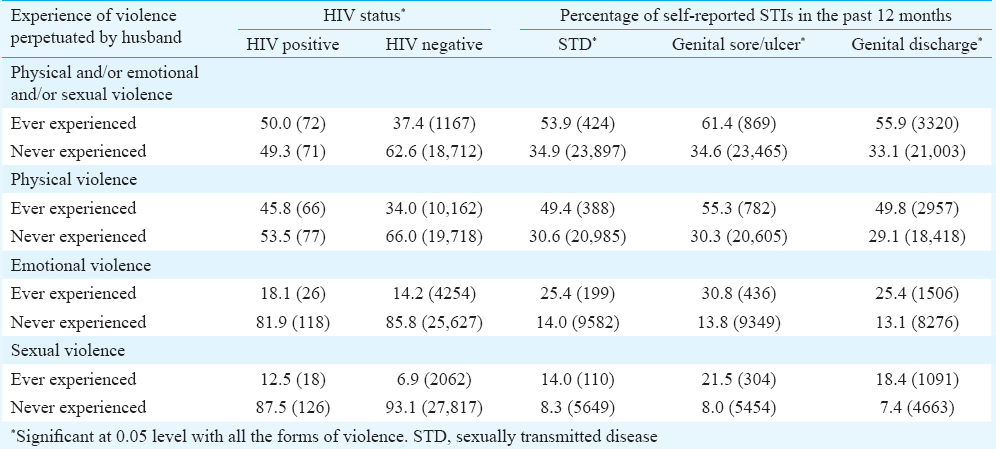

Association of violence with STIs and HIV: Table IV depicts the percentage of women by HIV status and women who reported having STDs, genital sore/ulcer and genital discharge in the 12 months preceding the survey. NFHS-3 indicated that 0.28 per cent of adults age 15-49yr were infected with HIV. The HIV prevalence rate was 0.22 per cent for women (95% CI=0.23-0.33)12. When the association of violence with HIV was studied, it revealed that higher percentage of HIV-positive women reported experiencing violence as compared to women who never experienced violence. Overall, a total of 786 women (1.1%) reported having STD, 1415 (2.0%) reported having genital sore/ulcer and 5941 women (8.5%) reported having genital discharge in the past 12 months. Higher percentage of women experiencing violence reported STIs. The odds of reporting STIs with the exposure of violence were calculated. The OR was significant and equal to 2.20 (95% CI=0.91-2.56) of having STD for women reporting IPV. Similarly, significantly higher proportion of women experiencing IPV reported genital sore/ulcer (OR=3.02, 95% CI=2.71-3.37) and genital discharge (OR=2.55, 95% CI=2.41-2.69).

Discussion

The past two decades have seen an increase in both international attention and programmatic efforts towards developing interventions to prevent and respond to violence against women. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study ranks IPV as 5th in years of life lost as a result of disability for women18. Our analysis showed a high prevalence of violence against women in India (35.3%). Other studies overestimated lifetime prevalence of IPV in the range of 20-50 per cent219. WHO multi-country study1 on IPV in 10 countries estimated physical violence in the range of 13-61 per cent and sexual violence at 6-59 per cent. Our findings corroborated with the studies carried out in both developed and developing countries161920212223.

The findings from our study demonstrated some key predictors associated with IPV, such as younger age of women, higher number of children, low level of education of women as well as her partner, working status of women, alcohol consumption by husband, higher spousal age, rural residence, nuclear household and lower standard of living. Studies conducted worldwide have attempted to explain several of these factors and their interplay with violence against women32425.

IPV and HIV are hypothesized to have critical intersections, and women's vulnerability to HIV may be influenced by violence caused by culturally accepted gender inequalities26. The finding of our study about a significant positive association between HIV status and IPV in married women in general population in India hints towards new pathways that link violence and HIV. It suggests that the pathways do not rely almost exclusively on higher risk behaviours, but IPV in married women may also be an independent risk factor for HIV. Our analysis showed HIV-positive status of women as well as women from high HIV prevalent State to be positively associated with experiencing sexual violence with increased odds. Our study also showed an association between violence and STIs. Dunkle and Decker27 have suggested a possible intersection of IPV with HIV infection. HIV transmission risk is higher in the presence of other STIs and when exposed to sexual secretions and/or blood28. IPV is an important correlate of a wide range of adverse reproductive health outcomes for women, including STIs25. However, much of the evidence pertains to the developed world and draws heavily on data from patients at STI clinics or women in IPV shelters29, leaving largely unanswered the question of whether the positive IPV-STI association is equally applicable to women in the general population of developing countries. Our study analysis provides the association in general population at a national level for India.

While the evidence is not conclusive, research suggests that violence limits women's ability to negotiate condom use3031. Violence or fear of violence has also been implicated as a barrier to disclosure of HIV status among those women who do seek testing. For many women worldwide, the threat of violence exacerbates their risk of contracting HIV. Studies show the increasing links between violence against women and HIV and demonstrate that HIV-infected women are more likely to have experienced violence and those women who experience violence are at higher risk for HIV3233. A systematic review and meta-analysis on association between IPV and HIV pooled results of 28 studies indicated that physical IPV [pooled relative risk (RR) (95% CI): 1.22 (1.01, 1.46)] and any type of IPV [pooled RR (95% CI): 1.28 (1.00, 1.64)] were significantly associated with HIV infection among women34. Our findings support arguments that partner violence increases women's risk of HIV and STIs.

Limitations of the current study included the inability to establish a temporal relationship based on the cross-sectional nature of the data. There could be recall and information bias as STIs were self-reported and retrospective. Because of the sensitivities attached with violence, it was possible that women underreported their experience owing to social desirability bias. To conclude, our data analysis indicated all forms of violence against women to be prevalent in India. This study also showed a significant association between HIV/STIs and IPV contributing considerably to women's vulnerability to HIV and STIs.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) for supplying the data of NFHS-3 survey.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- WHO multi-country study on women's health and IPV against women: Summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

- IPV in India: A summary report of a multi-site household survey. Washington, DC: International Council for Research on Women; 2000.

- IPV and women's health in India: Evidence from Health Survey. Germany: University Library of Munich; 2008.

- Violence against women, vulnerabilities and disempowerment: Multiple and interrelated impacts on achieving the Millennium Development Goals in South Africa. Agenda. 2012;26:20-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate partner violence. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/

- Determinants of child and forced marriage in Morocco: Stakeholder perspectives on health, policies and human rights. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Partner violence as a risk factor for mental health among women from communities in the Philippines, Egypt, Chile, and India. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2004;11:125-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- IPV and its mental health correlates in Indian women. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:62-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on IPV against women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2007.

- National Family Health Survey 2005-2006 (NFHS-3) India Reports. Available from: http://hetv.org/india/nfhs

- Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- In India Poverty and lack of education are associated with men's physical and sexual abuse of their wives. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2000;26:44-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- INCLEN. Domestic violence in India 3: A summary report of a multi-site household survey. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women and the Center for Development and Population Activities; 2000.

- A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41:673-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlates of intimate partner physical violence among young reproductive age women in Mysore, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2014;26:169-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for domestic physical violence: National cross-sectional household surveys in eight southern African countries. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:11.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998-1999. Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2000.

- State accountability for wife-beating: The Indian challenge. Lancet. 1997;349(Suppl 1):sI10-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wife-beating in rural South India: A qualitative and econometric analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1169-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- IPV and women's health in India: Evidence from Health Survey. Germany: University Library of Munich; 2008.

- Profiling domestic violence – A multi-country study. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro; 2004.

- 2004. World Health Organization. Violence against women and HIV/AIDS: Critical intersections-intimate partner violence and HIV/AIDS. Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/pht/InfoBulletinIntimatePartnerViolenceFinal.pdf

- Gender-based violence and HIV: reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):20-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Religious affiliation, denominational homogamy, and IPV among US couples. J Sci Study Relig. 2002;41:139-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- When HIV-prevention messages and gender norms clash: The impact of domestic violence on women's HIV risk in slums of Chennai, India. AIDS Behav. 2003;7:263-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: Findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:125-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. 2004 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: 4th global report. Available from: http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2004/GAR2004_en.pdf

- World Health Organization. Gender dimensions of HIV status disclosure to sexual partners: Rates, barriers and outcomes: A review paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

- Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18845.

- [Google Scholar]