Translate this page into:

Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in iron deficiency anaemia of pregnancy – A pilot study

Reprint requests: Dr Kiran Guleria, Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University College of Medical Sciences & Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi 110 095, India e-mail: kiranguleria@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Despite routine iron supplementation and promotion of diet modification, iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) remains widely prevalent in our antenatal population. Recent studies in pediatric population have highlighted the role of Helicobacter pylori infection in IDA. This study was undertaken to study the effect of eradication therapy in H. pylori infected pregnant women with IDA.

Methods:

Randomized placebo-controlled double blind clinical trial was done on 40 antenatal women between 14-30 wk gestation, with mild to moderate IDA and having H. pylori infection, as detected by stool antigen test. These women were randomly divided into group I (n=20): H. pylori treatment group (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, omeprazole for 2 wk) and group II (n=20): placebo group. Both groups received therapeutic doses of iron and folic acid. Outcome measures were improvement in haematological parameters and serum iron profile after 6 wk of oral iron therapy.

Results:

The prevalence of iron deficiency in pregnant women with mild to moderate anaemia was 39.8 per cent (95% CI 35.7, 44.3); and 62.5 per cent (95% CI 52, 73) of these pregnant women with IDA were infected with H. pylori. After 6 wk of therapeutic oral iron and folic acid supplementation, the rise in haemoglobin, packed cell volume, serum iron and percentage transferrin saturation was significantly (P<0.05) higher in the group given H. pylori eradication therapy as compared to the placebo group.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our results showed a high occurrence of H. pylori infection in pregnant women with IDA. Eradication therapy resulted in significantly better response to oral iron supplementation among H. pylori infected pregnant women with IDA.

Keywords

Eradication therapy

Helicobacter pylori

iron deficiency anaemia

pregnancy

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency in the world and results in impairment of immune, cognitive and reproductive functions, as well as decreased work performance1. Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) affects more than a billion people worldwide and contributes to up to 40 per cent of maternal deaths in the developing countries2–4. In a typical singleton pregnancy, about 600 mg of iron is required, which amounts to 4-6 mg per day of absorbed iron. Since diet alone cannot supply this amount of iron, additional supplementation is needed5. But despite routine supplementation, many women continue to remain anaemic6. Hence there is a need to review the additional factors affecting gastric absorption and utilization of dietary or supplemental iron. Helicobacter pylori, the curved Gram-negative ciliated bacillus, implicated in gastric ulcers and gastric cancer has been shown to be associated with IDA7–10. A recent meta-analysis of 12 case reports and series, 19 observational epidemiologic studies and six interventional trials concluded H. pylori infection to be a major risk factor for iron deficiency or IDA especially in high risk groups. The pooled OR for the development of IDA was found to be 2.8 (CI 1.9, 4.2) and the need for further research into the impact of H. pylori therapy on iron stores was emphasized11. In pregnant women, it has been found to be associated with low initial haemoglobin (Hb), unfavourable change in Hb during the course of pregnancy and a high chance of growth retardation and H. pylori infection in children of these mothers1213. Various mechanisms have been hypothesized for the development of IDA in H. pylori infection; some of which are low gastric pH, low vitamin C levels in stomach, sequestration of serum iron and ferritin by gastric H. pylori114–16. Though interventional studies conducted in paediatric population have shown improvement in IDA with H. pylori eradication, even without iron replacement7–10, there is paucity of such clinical trials in pregnant women. Several investigators have evaluated the safety of individual drugs, including proton pump inhibitors used in the anti H. pylori triple drug therapy in pregnant women and the meta-analysis reports no increased risk for spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery or major congenital birth defects1718.

Thus the present pilot study was planned to examine the impact of eradication therapy on response to therapeutic oral iron folate supplementation in H. pylori infected pregnant women with IDA.

Material & Methods

This randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial was conducted from December 2005 to March 2007 in the Departments of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Pathology and Microbiology of University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee.

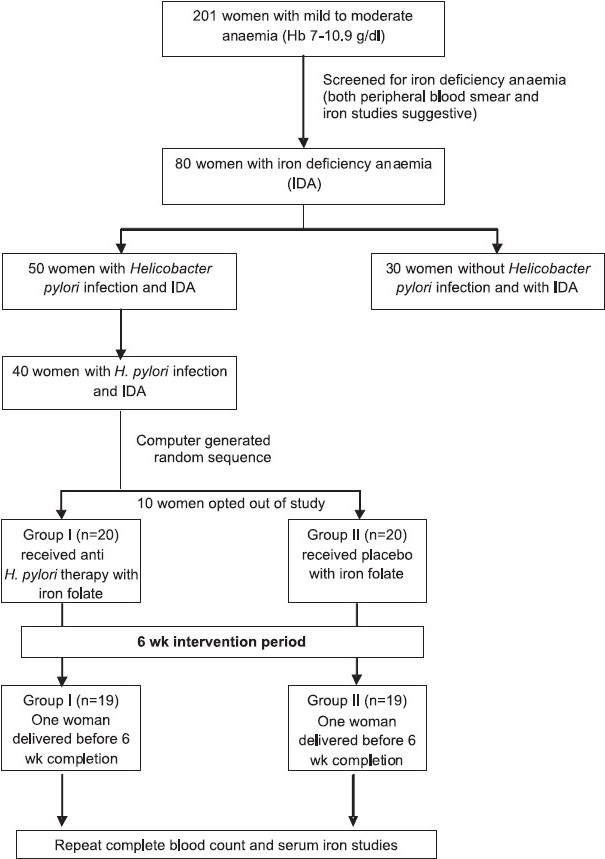

Recruitment of study subjects: Since there was no background data available on the expected prevalence of H. pylori in pregnancy or impact of eradication therapy in pregnant women with IDA, this trial was conducted as a pilot study (Fig.). In order to lend statistical power to study, the aim was to recruit a minimum of 40 H. pylori infected iron deficient anaemic women. The process started with a random screening of pregnant women who had Hb between 7 to 10.9 g per cent as per routine antenatal clinic testing. They further underwent serum iron studies. Those with confirmed IDA were then subjected to stool antigen testing to determine their H. pylori infection status.

- Flow chart showing study design.

Diagnosis of IDA1920: Complete blood count [Hb, packed cell volume (PCV), red blood cell count (RBC), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet count, total leukocyte count (TLC)] was done using T890 Coulter automated blood cell counter (Beckman Coulter Inc, USA). Peripheral blood smear was evaluated after staining the slides with Standard Wright's stain. Reticulocyte count was done using New Methylene blue staining. Tests for iron deficiency [serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), percentage transferrin saturation] were done1920 and serum ferritin determined by ELISA kit (Dia Metra, Italy). The diagnosis of iron deficiency was established when serum iron was <60 μg/dl, serum TIBC was >350 μg/dl and percentage saturation was <16 per cent21.

Diagnosis of H. pylori infection: Women with established iron deficiency anaemia underwent stool antigen testing for H. pylori (premium platinum HpSA kit, Meridian biosciences Inc, USA). This is a rapid enzyme immunoassay, which uses monoclonal anti H. pylori capture antibodies adsorbed to plastic wells of ELISA tray. Diluted stool samples and conjugate (peroxidase conjugated to monoclonal antibodies) were added to wells and incubated. Colour was developed in presence of bound enzyme and was interpreted spectrophotometrically (OD 450 recorded with air at zero, positive and negative cut-offs were as based on the manufacturer's protocol). Women with history of having taken antacids or antibiotics in past one month were excluded as it interferes with test results.

Finally, 40 women between 14 to 30 wk gestation with mild to moderate IDA and H. pylori infection were included in the study. Those with severe anaemia, megaloblastic or normocytic normochromic anaemia and known bleeding diathesis were excluded. All women confirmed their participation by signing a written informed consent form.

A detailed history, and physical and obstetric examination were carried out for all recruited women, who were further randomized for the purpose of treatment into: Group I (n=20): who received H. pylori eradication treatment and therapeutic iron and folic acid supplementation, and Group II (n=20): who received placebo and therapeutic iron folic acid supplementation.

Women were each assigned a sequential serial number and directed to third party for drug dispensing. This third party dispensed anti H. pylori therapy or placebo as per computer generated random number sequence, which was not known to the investigators.

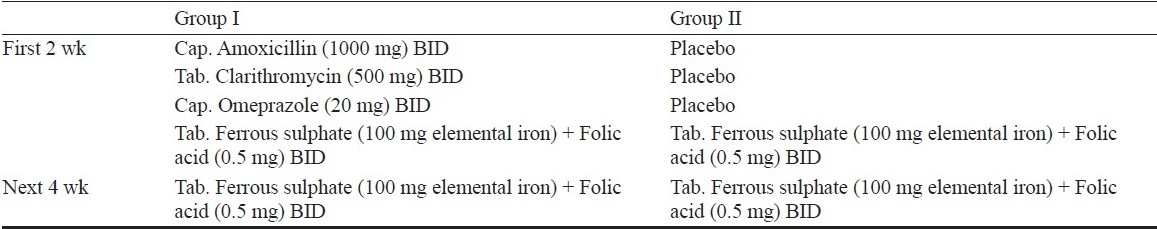

For the purpose of blinding, placebo capsules were prepared using sucrose as filler identical to amoxicillin capsules and omeprazole capsules. Tablet clarithromicin was put into capsules so that corresponding placebos could be made. The drug dosage schedule is shown in Table I.

Each day's drug/placebo was dispensed in identical brown packets, to be taken by women 1 h before meals and separate from oral iron folic acid tablets, as iron absorption may be hampered by omeprazole due to rise in gastric pH. Women were called for follow up after 72 h and then weekly to assess compliance, intolerance, and any side effects. At every visit, patients were enquired about intolerance, GI disturbances and they were all followed up till delivery to collect data regarding abortion, preterm delivery or low birth weight. Routine antenatal care was provided to all women and they continued to receive therapeutic iron and folic acid supplementation even after the study period of 6 wk was over.

The compliance was almost 100 per cent as all study subjects were under close follow up. The outcome measure was to assess the improvement in haematological parameters (complete blood count and serum iron studies) following interventional therapy, in response to iron folate supplementation for 6 wk. In case a woman delivered before 6 wk duration, only haemoglobin could be done. Serum samples collected at the time of serum iron studies were also stored frozen for serum ferritin analysis to be done at a later date. Due to limited number of ferritin kits available, paired (before and after treatment) samples of only 9 subjects were randomly selected for analysis,. Since the samples were identified only with laboratory numbers, investigators were unknown to the identity or study group of the subjects or their iron profiles.

Non parametric tests were used to analyze the data. Pre intervention values of all parameters were compared between group I and group II by Mann Whitney U test. Change (post -pre) was calculated for each parameter and the change was compared between the groups by Mann Whitney U test. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare pre- and post-values of each group separately. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

With an aim to recruit 40 H. pylori positive pregnant women with IDA, 201 antenatal women in second and third trimesters with Hb between 7 and 10.9 g% (as detected in the routine screening done at first hospital visit) were investigated for the type of anaemia. Of these, 80 (39.8%; 95% CI 35.7, 44.3) were confirmed to have iron deficiency anaemia. The remaining 121 subjects did not qualify for recruitment criteria of microcytic hypochromic anaemia on peripheral blood smear or serum iron parameters. They either had dimorphic anaemia on smear or the serum iron values were in normal range. Fifty (62.5%; 95% CI 52, 73) of these 80 women with IDA were infected with H.pylori (as per the stool antigen detection test). Thus the occurrence of H. pylori infection in mild to moderate IDA of pregnancy was 62.5 per cent. Ten of these 50 H. pylori infected women refused to participate in the interventional trial.

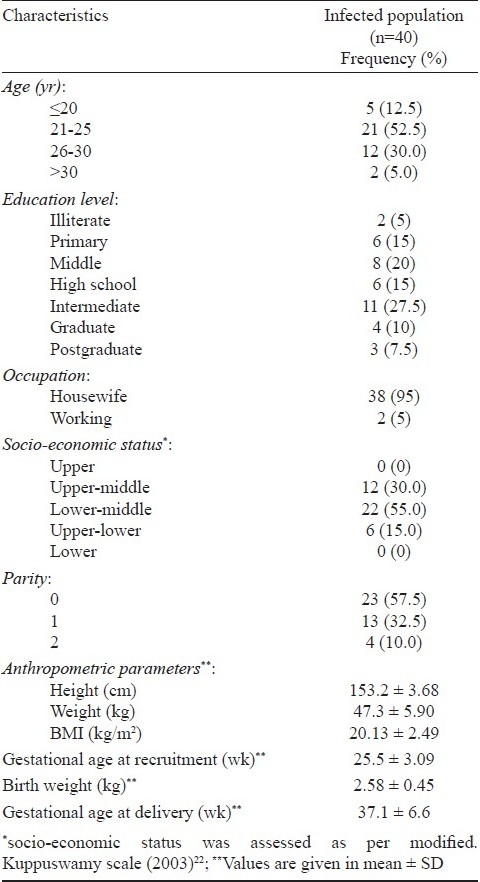

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of H. pylori infected pregnant women with IDA (study participants) are depicted in Table II. These women were predominantly young (less than 25 yr), middle class, primiparas and housewives with average BMI. Dyspepsia was not found to be a consistent feature of H. pylori infection. Due to the process of randomization for allocating a woman to treatment or placebo groups, the two groups are expected to be similar with regard to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics and hence these were studied as single group for these characteristics.

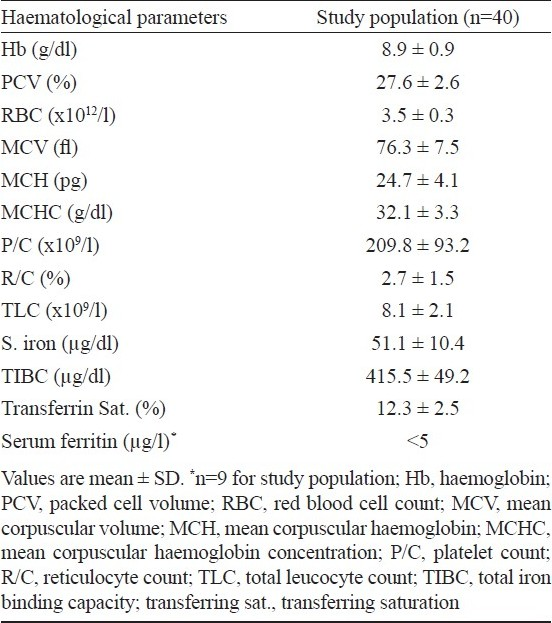

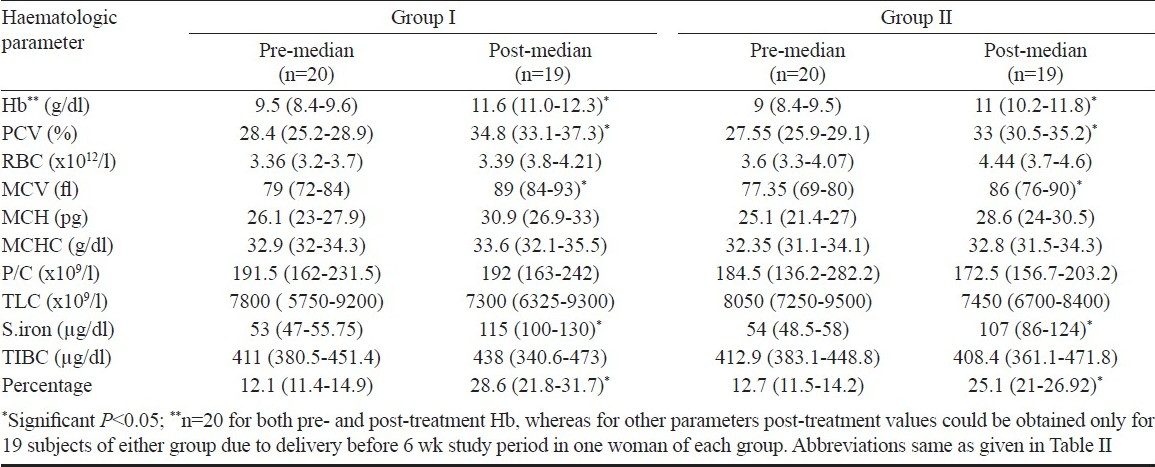

The baseline haematological variables of recruited women are shown in Table III. Serum ferritin could be done only in a subset of women (9 of 40 infected) because of economic constraints. As expected, the mean serum ferritin levels were below normal in all of the recruited subjects.

The study population was further grouped into treatment (H. pylori eradication) and placebo groups and followed up after iron folate supplementation for six weeks. Due to the randomization process, the haematological variables were comparable in the two study groups before intervention. The median values of haematological parameters in the individual groups (treated and placebo groups), before and after intervention are shown in Table IV. There was significant improvement in median Hb, PCV, MCV, serum iron and percentage transferrin saturation over their baseline in both the groups.

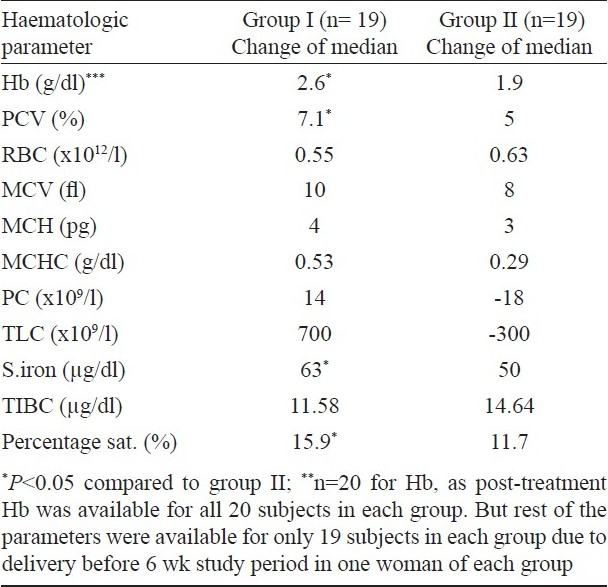

The change in median haematological parameters was compared between treated (group I, n=19) and placebo (group II, n=19) groups (Table V). Two women (one each from placebo and drug group) delivered premature and only post-treatment haemoglobin levels could be evaluated in them (n=20 for Hb). The change in median Hb (P<0.05) and PCV (P<0.05) was significantly higher in the treated group (group I) as compared to placebo group (group II). There was no significant difference in the change of median of other parametres. The change of median serum iron and percentage transferrin saturation in the women who received eradication therapy (group I) was significantly better (P<0.05). Both groups showed significant rise in mean serum ferritin levels after six weeks of iron folate supplementation; treated group (11.6 ± 7.7 μg/l) showing a marginally better response than placebo group (11.2 ± 6.6 μg/l).

The mean birth weight of neonates in the two groups was comparable and none of the babies had any congenital malformation. No significant adverse effect of the H. pylori eradication regimen was noted in pregnant women.

At the time of data analysis, when the random sequence was disclosed, the women in the placebo group were contacted and prescribed the H. pylori eradication therapy.

Discussion

As per the hospital registration record, 33118 women attended the antenatal clinic of our hospital during the study period. A policy of routine Hb screening at the first visit was adopted in the hospital, according to which 57.05 per cent had mild to moderate anaemia (Hb 7 to 10.9 g %) and 1.26 per cent had severe anaemia (Hb <7 g %). Pure iron deficiency in mild to moderate anaemic women was found to be 39.8 per cent. In the present study, 62.5 per cent of these subjects had infection with H. pylori, indicating a high prevalence in our pregnant population with IDA. However, prevalence of H. pylori infection in European pregnant population was found much less and ranged between 18-23 per cent only132324. Although Lancier et al23 have suggested that pregnancy may by itself increase the susceptibility to H. pylori infection due to changes in the humoral and cell mediated immunity24, the high occurrence found in the present study may reflect a high H. pylori infection background prevalence in general population in our country. Valiyaveetil et al25 in their study of H. pylori infection in adults with IDA in south India also found a high prevalence (61.5%). This high prevalence can be explained by differences in genetic and socio-economic factors, the spread of infection being specially facilitated by overcrowding, poor sanitation and living conditions, which are more prevalent in developing countries like ours2627.

We used the stool antigen test which is an FDA approved simple diagnostic test with sensitivity and specificity of 94.3 and 91.8 per cent respectively28, whereas other diagnostic modalities for H. pylori are of limited use in pregnancy due to their invasive nature (biopsy-urease test), use of radioactive nucleotide (urea breath test) or inability to differentiate recent and remote infection (serology).

Young age of recruited subjects is a pointer towards early acquisition of infection in our population. Also, infection was present in women from all socio-economic strata and educational profile, which contrasted with the data obtained from the developed countries, where researchers found a high prevalence in low economic strata13. Dyspepsia was not found to be a consistent feature of infection. Many earlier studies have refuted the association of H. pylori infection and dyspepsia2930.

Weyermann et al13 found the H. pylori infected women to be having lower Hb at the beginning of pregnancy and an unfavourable change in Hb during the course of pregnancy. Farag et al31 also reported higher odds of H. pylori infection in women with severe anaemia, but only among those who were consuming diets with low heme iron. The relatively high (near normal) percentage saturation and serum iron levels in the recruited subjects may be an indirect marker of a short term insult to the erythropoesis due to H. pylori infection, which acts as a limiting factor in the iron utilization for erythropoesis. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the H. pylori induced IDA, including the effect of H. pylori induced gastritis on gastric acid secretion and hence intragastric pH, decrease in the gastric ascorbic acid levels, sequestration of iron from lactoferrin by special receptors on the bacillus11416. It has also been suggested that these sequestering proteins are preferentially expressed in iron deficient states, thus predisposing to IDA in nutritionally vulnerable states like children and pregnant women7–1016.

Several researchers have examined the effect of H. pylori eradication on IDA in children and nonpregnant adults, showing improvement of refractory iron deficiency anaemia even without iron replacement8–1025. But there are insufficient data on similar beneficial effect of anti-H. pylori therapy in pregnancy. In the present study conducted in pregnant women with IDA, the response to oral iron folic acid supplementation was significantly better after H. pylori eradication therapy. Infected treated group showed significantly better change in median Hb and PCV levels than the placebo group. A significantly greater improvement was seen in serum iron profile after eradication therapy. Serum ferritin also showed a better improvement in the eradication group.

The small number of study subjects was a limitation of the present study. Also, serum ferritin could not be done for all study subjects due to financial constraints. Further, longer follow up even after cessation of iron therapy will truly reflect the efficacy of eradication therapy in IDA of pregnancy.

In conclusion, high prevalence of H. pylori infection was seen in pregnant women suffering from iron deficiency anaemia. The infection can be eradicated safely with triple drug therapy that significantly enhances the response to oral iron folic acid supplementation in pregnant women suffering from IDA. Further studies on a large number of women with a longer follow up of at least 12 to 24 months are recommended.

Authors thank the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, for partly funding the study.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests.

References

- Iron deficiency and Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:127-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences. Nutrition and prevalence of anaemia. National Family Health Survey-II (NFHS-II) 2002:247-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. In: The prevalence of anaemia in women: a tabulation of the available information (2nd ed). Geneva: WHO; 1992.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hematological disorders. In: Cunningham FG, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap L, Bloom SL, Wesntron KD, eds. Williams obstetrics (22nd ed). New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. p. :1143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the use of iron supplements to prevent and treat iron deficiency anaemia. Washington DC: INACG ILSI Press; UNICEF, WHO; 1998. p. :1-39.

- ICMR Task Force study. In: Evaluation of the national nutritional anaemia prophylaxis programme. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1989.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter pylori-associated iron deficiency anaemia in adolescent female athletes. J Pediatr. 2001;139:100-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Refractory iron deficiency anaemia due to silent Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:177-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there a relationship between childhood Helicobacter pylori infection and iron deficiency anaemia? J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:166-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of long-standing iron-deficiency anaemia in adults after eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Intern Med. 2002;41:491-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter pylori infection and iron stores: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2008;13:323-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Children of Helicobacter pylori-infected dyspeptic mothers are predisposed to H.pylori acquisition with subsequent iron deficiency and growth retardation. Helicobacter. 2005;10:249-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in iron deficiency during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:548-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactoferrin sequestration and its contribution to iron deficiency anaemia in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:980-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron deficiency anaemia and Helicobacter pylori infection: a review of the evidence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:453-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concomitant alterations in intragastric pH and ascorbic acid concentration in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis and associated iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2003;52:496-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- The safety of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1541-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drugs in pregnancy and lactation (7th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2005.

- Recommendations for measurement of serum iron in human blood. Br J Haematol. 1978;38:291-4. [No authors listed]

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum unsaturated iron binding capacity. Tech Bull Regist Med Technol. 1958;28:121-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Means Jr. Anaemias during pregnancy and the postpartum period. In: Greer JP, Foerster, Rodgers GM, eds. Wintrobe's clinical hematology (12th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale - a revision. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:273-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased susceptibility to Helicobacter pylori infection in pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1999;7:195-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in asymptomatic pregnant women in France. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:736-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy on outcome of iron- deficiency anaemia: a randomized, controlled study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:155-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Position paper on Helicobacter pylori in India.Indian Society of Gastroenterology. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1997;16(Suppl 1):S29-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reservoirs and routes of transmission of Helicobacter pylori in India. Indian J Gasteroenterol. 1997;16(Suppl 1):S9-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accurate diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori Stool tests. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:917-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dyspeptic complaints after 20 weeks of gestation are not related to Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:CR 445-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:845-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with severe anaemia of pregnancy on Pemba Island, Zanzibar. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:541-8.

- [Google Scholar]