Translate this page into:

Seroprevalence & seroincidence of Orientia tsutsugamushi infection in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: A community-based serosurvey during lean (April-May) & epidemic (October-November) periods for acute encephalitis syndrome

For correspondence: Dr Suchit Kamble, Division of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, ICMR-National AIDS Research Institute, 73, G-Block MIDC Bhosari, Pune 411 026, Maharashtra, India e-mail: skamble@nariindia.org

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

In India, acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) cases are frequently reported from Gorakhpur district in Uttar Pradesh. Scrub typhus is one of the predominant aetiological agents for these cases. In order to delineate the extent of the background of scrub typhus seroprevalence and the associated risk factors at community level, serosurveys during both lean and epidemic periods (phase 1 and phase 2, respectively) of AES outbreaks were conducted in this region.

Methods:

Two community-based serosurveys were conducted during lean (April-May 2016) and epidemic AES (October-November 2016) periods. A total of 1085 and 906 individuals were enrolled during lean and epidemic AES periods, respectively, from different villages reporting recent AES cases. Scrub typhus-seronegative individuals (n=254) during the lean period were tested again during the epidemic period to estimate the incidence of scrub typhus.

Results:

The seroprevalence of Orientia tsutsugamushi during AES epidemic period [immunoglobulin (Ig) IgG: 70.8%, IgM: 4.4%] was high as compared to that of lean AES period (IgG: 50.6%, P<0.001; IgM: 3.4%). The factors independently associated with O. tsutsugamushi positivity during lean AES period were female gender, illiteracy, not wearing footwear, not taking bath after work whereas increasing age, close contact with animals, source of drinking water and open-air defecation emerged as additional risk factors during the epidemic AES season. IgM positivity was significantly higher among febrile individuals compared to those without fever (7.7 vs. 3.5%, P=0.006). The seroincidence for O. tsutsugamushi was 19.7 per cent, and the subclinical infection rate was 54 per cent.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The community-based surveys identified endemicity of O. tsutsugamushi and the associated risk factors in Gorakhpur region. The findings will be helpful for planning appropriate interventional strategies to control scrub typhus.

Keywords

Acute encephalitis syndrome

community-based

Orientia tsutsugamushi

scrub typhus

seroincidence

seroprevalence

serosurvey

Rickettsial diseases are considered under the covert emerging and re-emerging diseases and are being increasingly recognized in the Indian subcontinent1. Among these, scrub typhus, an acute febrile illness caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, is commonly reported among febrile hospitalized patients from different parts of India2345678. Acute meningoencephalitis has been reported as one of the complications with scrub typhus91011. In India, acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) cases are frequently reported from Gorakhpur district in Uttar Pradesh, occurring predominantly during the monsoon season and affecting children1213. Reports from investigations conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India, and studies conducted in this region identified scrub typhus as one of the predominant aetiological agents of AES based on immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody detection or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test in cerebrospinal fluid samples1214. Scrub typhus-related studies conducted in this region have included patients from hospital setting; however, the scenario at community level remains largely unexplored.

The Department of Health Research, the Government of India and ICMR undertook various epidemiological, clinical, entomological and ecological studies to resolve the complexities revolving around scrub typhus in this region. As a part of this investigation and delineate the extent of the background of the seroprevalence of O. tsutsugamushi infection and the associated risk factors, community serosurveys were conducted during both lean and epidemic periods of AES outbreaks. Further, the incidence of O. tsutsugamushi seroconversion from lean to epidemic AES period was also estimated.

Material & Methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the ICMR-National AIDS Research Institute (ICMR-NARI), Pune (NARI EC/2015-24 and NARI EC/2016-15). Written informed consent from all participants and assent for minors was obtained before enrolment in the study.

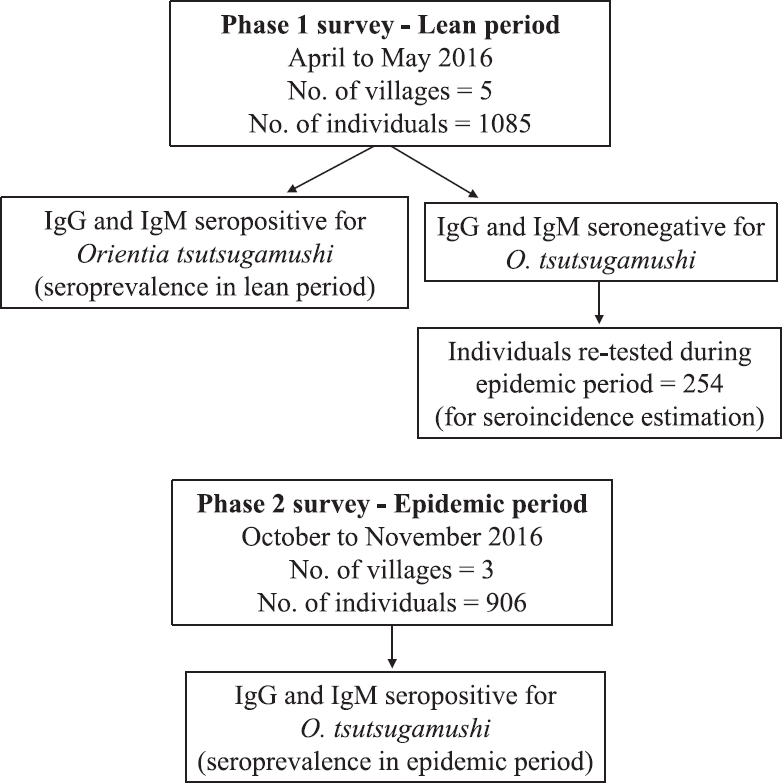

In Gorakhpur district, AES cases start appearing at the beginning of monsoon season from July onwards, reach the peak reporting in August-September and then start declining from October-November15. During the rest of the year, very few cases are reported within the district. Therefore, the period between July and November was considered as the epidemic AES period, whereas rest of the months were considered as lean AES period. For the estimation of O. tsutsugamushi seroprevalence, cross-sectional, community-based serosurveys were conducted, first during the lean period between April and May 2016 (phase 1 survey) and second towards the end of the epidemic period during October-November 2016 (phase 2 survey) to pick up all new infections occurring during the epidemic period. For determination of the incidence of seroconversion, the participants who were seronegative for both IgG and IgM antibodies to O. tsutsugamushi during the phase 1 lean period were retested during the phase 2 AES epidemic period (Figure).

- Flow diagram showing sample collection during phase 1 and phase 2 surveys.

Study area: A block-wise line list of AES cases detected in Gorakhpur district from January to December 2015 was obtained from Gorakhpur unit, National Institute of Virology, Pune, and arranged in descending order. Maximum number AES cases with unknown aetiology were reported in five blocks namely, Chargaon (78), Sadar (47), Pipraich (39), Khorabar (31) and Jungle Couria (29). Hence, villages from these five blocks in Gorakhpur district were considered for O. tsutsugamushi serosurvey which contributed to 50 per cent AES cases with undiagnosed aetiology in this district.

Selection of villages for serosurvey: From each of the selected block, the village or urban ward reporting the recently occurring AES case with an unknown aetiology was selected for phase 1 serosurvey. After confirming the endemicity of scrub typhus in phase 1 serosurvey, the phase 2 serosurvey was done to understand IgM positivity during the epidemic period. During phase 2 survey, the re-entry in the villages from phase 1 was found difficult as there was lack of support from the local administrators and poor response. The recent AES cases were also reported from different villages during the two serosurvey phases, and hence, three other villages were included during the phase 2 survey. Phase 1 survey was conducted in five villages (Belakata, Hamimpur, Kazipur, Rajhi and Vikas Nagar), whereas phase 2 survey was conducted in three different villages (Chilona, Dhabahi and Jungle Dumbri). However, the methodology for selection of participants remained the same across the two phases.

The sample size was calculated based on a previous unpublished report of IgM seroprevalence for scrub typhus in Gorakhpur district as 20 per cent. A sample size of 323 was considered adequate assuming 30 per cent prevalence, 95 per cent confidence level and five per cent absolute precision. We expected gradient of infection as per age, so to capture this, samples from three different age groups namely, 6-15, 16-25 and >25 yr were collected.

Selection of study participants: The recently reported AES case was treated as an index case from each of the selected blocks. Households in all directions of this index case were screened for enrolment until the target sample size in each age group was achieved. In each household, all members were enlisted as per the three age groups mentioned above. From each household, only one member was selected randomly for each age group by Kish table15 to get adequate representation of each group. If the selected member refused or was unavailable on the three visits, the selected participant was omitted from the survey. Screening of households was continued simultaneously in all directions till adequate sample size in each age group was achieved. A structured questionnaire was used to collect information on sociodemographics, environmental determinants, personal hygiene and clinical symptoms along with treatment history. Additional information on contact with bushes, presence of ticks or mites on cattle/pets, defecation practices, etc., was collected from the participants during the phase 2 survey.

Individuals who tested negative for O. tsutsugamushi infection during the phase 1 survey were revisited again during the epidemic period and retested for the determination of incident scrub typhus infection. At least three attempts were made to enroll these seronegative respondents for retesting. A seronegative individual during the lean period who turned positive for scrub typhus (IgM or IgG) during epidemic season was considered as an incident case for seroconversion.

Blood sample collection and processing: Blood sample (4 ml) was collected from each participant and all serum samples were tested at the Central ICMR-NARI Microbiology Laboratory, Pune, for the presence of IgM and IgG antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi using commercial assays Scrub Typhus Detect IgM ELISA System and Scrub Typhus Detect IgG ELISA System (INBIOS International, Inc., USA), respectively. The tests were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For determination of cut-off for IgM ELISA, box-whisker plot was constructed for IgM optical density (OD) values from phase 1 and phase 2 surveys, the outlier OD values were removed and the cut-off of 0.55 for phase 1 and 0.78 for phase 2 survey was derived using mean±3 standard deviation. For IgG, a bimodal distribution of the IgG OD values in both surveys was seen, and hence, the cut-off of 1.5 at intercept of this distribution was considered for IgG ELISA.

Statistical analysis: To determine the risk factors associated with O. tsutsugamushi infection, statistical analysis was done using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. IgG positivity was taken as the dependent variable and sociodemographic, environmental and host factors were included as independent variables. All variables included in the univariable analysis were included further in multivariable regression analysis for explaining an independent association with the dependent variable. Cluster analysis was done to assess the clustering effect of the village. The data were cleaned and tabulated using statistical software IBM SPSS v15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Regression analysis was performed using STATA/IC 10 software [StataCorp. (2007) Stata Statistical Software. Release 10. College Station, StataCorp LP, Texas].

Results

A total of 1991 individuals were enrolled in this community-based survey, including 1085 during the phase 1 and 906 during the phase 2 serosurvey. Of the 1085 individuals surveyed during the lean period, 254 seronegative individuals were tested again during the epidemic period to determine the incidence of scrub typhus infection. Thus, a total of 2245 serum samples from 1991 individuals were tested throughout the study period.

Seroprevalence of O. tsutsugamushi infection and associated risk factors during phase 1 survey: A total of 1085 individuals were surveyed, with almost equal numbers of individuals in each of the three age groups targeted [6-15 yr=344 (32%), 16-25 yr=372 (34.29%) and >25 yr=369 (34%)]. The overall seropositivity against O. tsutsugamushi (IgG and/or IgM antibody) was 51.6 per cent (560/1085).

IgG seropositivity was seen in 50.6 per cent (549/1085) of participants (Table I). An increasing trend with IgG was observed along with the age groups [6-15 yr (36%), 16-25 yr (45%) and >25 yr (69%), P <0.001], and it was maximum in village Hamimpur (68%) followed by Belakata (65%), Kazipur (51%), Rajhi (39%) and Vikas Nagar (34%), (P <0.001). The risk factors associated with IgG seropositivity were female gender, illiteracy, not wearing footwear during outdoor activity and not taking bath after work (Table II).

| Characteristic | Phase 1 serosurvey | Phase 2 serosurvey | Re-tested individuals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | IgG seroprevalence n (%) | IgM seroprevalence n (%) | n (%) | IgG seroprevalence n (%) | IgM seroprevalence n (%) | n (%) | Seroincidence n (%) | |

| Overall | 1085 | 549 (50.6) | 37 (3.4) | 906 | 641 (70.8) | 40 (4.4) | 254 | 50 (19.7) |

| Age group (yr) | ||||||||

| 6-15 | 344 (32) | 125 (36) | 12 (3.5) | 288 (32) | 156 (54) | 12 (4.2) | 92 (36) | 12 (13) |

| 16-25 | 372 (34.29) | 168 (45) | 8 (2.1) | 288 (32) | 214 (74) | 9 (3.1) | 108 (43) | 23 (21) |

| >25 | 369 (34) | 256 (69) | 17 (4.6) | 330 (36) | 271 (82) | 19 (5.8) | 54 (21) | 15 (28) |

| Gender* | ||||||||

| Male | 527 (49) | 212 (40) | 15 (2.8) | 460 (51) | 292 (63) | 15 (3.3) | 141 (56) | 24 (17) |

| Female | 555 (51) | 336 (61) | 22 (4.0) | 446 (49) | 349 (78) | 25 (5.6) | 113 (44) | 26 (23) |

*Information about gender not available for 3 participants

| Characteristic | Number of individuals, n (%) | IgG positive n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (yr) | |||||

| 6-15 | 344 (32) | 127 (37) | 1 | 1 | |

| 16-25 | 372 (34) | 168 (45) | 1.4 (1.04-1.9) | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | 0.231 |

| >25 | 369 (34) | 254 (69) | 3.8 (2.8-5.1) | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) | 0.087 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 527 (49) | 212 (40) | 1 | 1 | |

| Female | 555 (51) | 336 (61) | 2.3 (1.8-2.9) | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | 0.004 |

| Education | |||||

| Literate | 792 (74) | 321 (40) | 1 | 1 | |

| Illiterate | 275 (26) | 221 (80) | 6 (4.3-8.3) | 3.3 (2.2-4.9) | <0.01 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Students | 368 (35) | 131 (36) | 1 | 1 | |

| Homemaker | 215 (20) | 159 (74) | 5.1 (3.5-7.4) | 1.6 (0.9-2.9) | 0.138 |

| Unemployed | 202 (19) | 103 (51) | 1.9 (1.3-2.7) | 1.4 (0.9-2.1) | 0.146 |

| Service/small business, etc. | 155 (15) | 72 (46) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 1.2 (0.7-2.03) | 0.606 |

| Agricultural labourers | 121 (11) | 79 (65) | 3.4 (2.2-5.2) | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) | 0.443 |

| Footwear for outdoor activity | |||||

| Yes | 952 (89) | 455 (48) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 119 (11) | 90 (76) | 3.4 (2.2-5.2) | 1.9 (1.1-3.3) | 0.015 |

| Daily bath with soap | |||||

| Yes | 951 (90) | 464 (49) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 106 (10) | 73 (69) | 2.3 (1.5-3.6) | 1.1 (0.6-0.97) | 0.743 |

| Taking bath after work | |||||

| Yes | 176 (17) | 77 (44) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 863 (83) | 456 (53) | 1.4 (1.04-2) | 1.5 (1.03-2.2) | 0.034 |

| Changing clothes daily | |||||

| Yes | 886 (86) | 438 (49) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 143 (14) | 87 (61) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 0.449 |

| Close contact with animals | |||||

| No | 739 (70) | 358 (48) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 315 (30) | 181 (57) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 0.244 |

| House type | |||||

| Kachcha* | 79 (8.1) | 40 (51) | 1 | - | |

| Pakka* | 284 (29) | 115 (40) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | - | |

| Kachcha-Pakka | 614 (63) | 320 (52) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) | - |

*Pakka house: Houses made with high-quality materials throughout, including the floor, roof and exterior walls; *Kachcha house: Houses made from mud, thatch or other low-quality materials. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio

IgM positivity was observed in 3.4 per cent (37/1085) of participants (Table I). The IgM positivity was not significantly different, across age groups [6-15 yr (3.5%), 16-25 yr (2.1%) and >25 yr (4.6%), P=0.182], gender [males (2.9%), females (4%)] and the villages surveyed [Belakata (4.3%), Hamimpur (2.6%), Kazipur (4.6%), Rajhi (1.3%) and Vikas Nagar (4.3%)]. No association between IgM positivity and any of the risk factors studied was observed (data not shown). A total of 2.7 per cent of individuals had a history of fever of more than five days duration during the survey, but none of them were IgM positive.

Seroprevalence of O. tsutsugamushi infection and associated risk factors during phase 2 survey: A total of 906 participants were enrolled, with almost equal numbers of individuals in each of the three age groups targeted [6-15 yr (288, 32%), 16-25 yr (288, 32%) and >25 yr (330, 36%)]. The overall seropositivity against O. tsutsugamushi (IgG and/or IgM antibody) was 71.5 per cent (648/906). IgG seropositivity was seen in 70.8 (641/906) per cent of participants (Table I). In this phase also, IgG positivity showed an increasing trend with age groups [6-15 yr (54%), 16-25 yr (74%), >25 yr (82%), P <0.001] with significant difference with respect to gender (male 63 vs. female 78%, P<0.001) and the three villages surveyed (65-75%, P=0.02). The risk factors associated with IgG seropositivity were female gender, increasing age, illiteracy, close contact with animals, source of drinking water and open-air defecation (Table III).

| Characteristic | Number of individuals, n (%) | IgG positive n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 460 (51) | 292 (63) | 1 | 1 | |

| Female | 446 (49) | 349 (78) | 2 (1.5-2.7) | 1.6 (1-2.4) | 0.017 |

| Age (yr) | |||||

| 6-15 | 288 (32) | 156 (54) | 1 | 1 | |

| 16-25 | 288 (32) | 214 (74) | 2.4 (1.7-3.4) | 2.5 (1.6-3.9) | 0.001 |

| >25 | 330 (36) | 271 (82) | 3.8 (2.6-5.5) | 2.5 (1.3-5) | 0.005 |

| Education | |||||

| Literate | 655 (72) | 423 (64) | 1 | 1 | |

| Illiterate | 251 (28) | 218 (86) | 3.6 (2.4-5.4) | 1.9 (1.1-3.3) | 0.013 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Student | 421 (46) | 256 (60) | 1 | 1 | |

| Unemployed | 61 (6.7) | 41 (67) | 1.3 (0.7-2.3) | 0.6 (0.3-1.2) | 0.174 |

| Homemaker | 228 (25) | 204 (89) | 5.4 (3.4-8.7) | 1.4 (0.6-3.2) | 0.321 |

| Agricultural labourers | 61 (6.7) | 46 (75) | 1.9 (1-3.6) | 0.8 (0.3-1.7) | 0.609 |

| Others | 135 (15) | 94 (69) | 1.4 (0.9-2.2) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | 0.319 |

| Footwear for outdoor activity | |||||

| Yes | 816 (90) | 573 (70) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 90 (10) | 68 (75) | 1.3 (0.9-2.1) | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) | 0.442 |

| Close contact with animals | |||||

| No | 421 (46) | 273 (64) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 485 (54) | 368 (75) | 1.7 (1.2-2.2) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 0.004 |

| Source of drinking water | |||||

| Hand pump | 755 (83) | 550 (72) | 1 | 1 | |

| Tap | 151 (17) | 91 (60) | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 0.5 (0.3-0.8) | 0.003 |

| Cattle shed nearby | |||||

| No | 231 (26) | 145 (62) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 675 (74) | 496 (73) | 1.6 (1.1-.2.2) | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) | 0.336 |

| Toilet practices | |||||

| Use of toilet | 245 (27) | 153 (62) | 1 | 1 | |

| Open-air defecation | 661 (73) | 488 (73) | 1.6 (1.2-2.3) | 1.6 (1.1-2.3) | 0.004 |

| Contact with bushes | |||||

| No | 109 (12) | 566 (71) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 797 (88) | 75 (68) | 0.9 (0.5-1.3) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) | 0.723 |

| Type of house | |||||

| Kachcha | 206 (23) | 148 (71) | 1 | 1 | |

| Pakka/Kachcha-Pakka | 700 (77) | 493 (70) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 1 (0.7-1.6) | 0.811 |

| Daily taking bath with soap | |||||

| Yes | 844 (93) | 593 (70) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 62 (6.8) | 48 (77) | 1.4 (0.7-2.6) | 1.2 (0.5-2.8) | 0.608 |

| Changing clothes daily | |||||

| Yes | 816 (90) | 571 (69) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 90 (10) | 70 (77) | 1.5 (0.8-2.5) | 1.3 (0.7-2.5) | 0.451 |

| Head/body louse infestation | |||||

| Yes | 124 (14) | 83 (66) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 782 (86) | 558 (71) | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) | 1.2 (0.7-2) | 0.367 |

IgM positivity was observed among 4.4 per cent (40/906) of participants (Table I). IgM positivity was significantly low among males as compared to females (3.3 vs. 5.6%, P=0.025), varied from 3.1 to 5.8 per cent across different age groups [6-15 yr (4.2%), 16-25 yr (3.1%) and >25 yr (5.8%)] and was comparable across the three villages surveyed [Chilona (4.3%), Dhabahi (3.5%) and Jungle Dumbri (5.4%)]. History of fever (current or in the last three months) was the only factor which showed association with IgM positivity in epidemic period [Adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=2.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.04, 4.26), P=0.037]. A total of 22 per cent of individuals had a history of fever of more than five days duration. IgM positivity among individual fever cases was significantly greater as compared to those without fever (7.7 vs. 3.5%, P=0.006). The overall O. tsutsugamushi seropositivity against IgG (P<0.01) and IgM was high during the AES epidemic period as compared with that of lean AES period (Table I).

Taking into account clustering at village level, cluster analyses were done for phase 1 and phase 2 surveys. In phase 1 multivariable analysis, the change in statistical significance due to robust standard errors (SE) was observed in the variable, taking bath after work [AOR=1.5, 95% CI (0.9, 2.6)]. In phase 2 multivariable analysis, robust SEs changed the statistical significance of the variable occupation [homemaker: AOR=1.5, 95% CI (1.2, 1.9); others: AOR=0.72, 95% CI (0.65, 0.79)].

Seroincidence of O. tsutsugamushi infection from lean to epidemic period: A total of 532 respondents were negative for both IgG and IgM antibodies during the phase 1 survey (lean period). It was possible to follow 254 (49%) individuals during AES epidemic period (phase 2 survey). The most common reasons for not being able to follow the remaining individuals were migration to other place either because of marriage or returning to the place of employment (52.3%) and misconception about giving blood sample (24%). There was no significant difference with respect to age, gender and literacy in individuals who were followed during the AES epidemic as compared to those who did not respond.

Of the 254 seronegative individuals, seroconversion during the AES epidemic period was observed in 50 (19.7%) individuals. Seroconversion rates showed a rising trend increasing with age [6-15 yr (13%), 16-25 yr (21%) and >25 yr (28%)]. The seroconversion rate was 17 per cent in males and 23 per cent in females. Illiteracy emerged as the only independent risk factor for seroconversion [AOR=13.1, 95% CI (2.2, 76.2), P=0.004] (Table IV).

| Characteristic | Number of individuals, n (%) | Incident cases, n (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 141 (56) | 24 (17) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 113 (44) | 26 (23) | 1.45 (0.8-2.7) | 0.234 | 1.36 (0.59-3.11) | 0.465 |

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| 6-15 | 92 (36) | 12 (13) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 15-25 | 108 (43) | 23 (21) | 1.8 (0.8-3.9) | 0.129 | 1.64 (0.66-4.07) | 0.289 |

| >25 | 54 (21) | 15 (28) | 2.6 (1.1-6.0) | 0.030 | 1.39 (0.33-5.84) | 0.653 |

| Education | ||||||

| Literate | 241 (95) | 40 (17) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Illiterate | 13 (5) | 10 (77) | 16.8 (4.4-63.6) | <0.01 | 13.1 (2.2-76.2) | 0.004 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Student | 165 (65) | 26 (16) | 1 | |||

| Homemaker | 29 (11) | 11 (38) | 3.3 (1.4-7.7) | 0.007 | 0.82 (0.16-1.3) | 0.818 |

| Agricultural labourer | 11 (4) | 3 (27) | 2.0 (0.5-8.1) | 0.327 | 1.12 (0.18-7.1) | 0.901 |

| Other | 49 (19) | 10 (20) | 1.4 (0.6-3.1) | 0.446 | 1.3 (0.44-4.1) | 0.605 |

| Close contact with animals | ||||||

| No | 171 (67) | 30 (18) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 83 (33) | 20 (24) | 1.5 (0.8-2.8) | 0.220 | 0.97 (0.36-2.5) | 0.943 |

| Source of drinking water | ||||||

| Hand pump | 155 (61) | 36 (23) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tap | 99 (39) | 14 (14) | 0.54 (0.3-1.07) | 0.078 | 0.65 (025-1.7) | 0.369 |

| Cattle shed nearby | ||||||

| No | 137 (54) | 23 (17) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 117 (46) | 27 (23) | 1.49 (0.8-2.7) | 0.211 | 1.07 (0.33-3.5) | 0.912 |

| Toilet practices | ||||||

| Use of toilet | 183 (72) | 28 (15) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Open air defecation | 71 (28) | 22 (31) | 2.48 (1.3-4.7) | 0.006 | 2.13 (0.78-5.9) | 0.142 |

| Contact with bushes | ||||||

| No | 122 (48) | 21 (17) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 132 (52) | 29 (22) | 1.35 (0.7-2.5) | 0.342 | 0.68 (0.22-2.1) | 0.495 |

| Type of house | ||||||

| Pakka | 141 (56) | 22 (16) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Kachcha/Kachcha-Pakka | 113 (44) | 28 (25) | 1.7 (0.9-3.3) | 0.070 | 1.16 (0.41-3.3) | 0.780 |

| Footwear for outdoor activity | ||||||

| Yes | 247 (97) | 47 (19) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 7 (3) | 3 (43) | 3.2 (0.7-14.7) | 0.137 | 2.05 (0.17-25.2) | 0.576 |

| Daily taking bath with soap | ||||||

| Yes | 234 (92) | 42 (18) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 20 (8) | 8 (40) | 3.05 (1.2-7.9) | 0.022 | 3.3 (0.63-17.2) | 0.158 |

| Changing clothes daily | ||||||

| Yes | 230 (91) | 44 (19) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 24 (9) | 6 (25) | 1.41 (0.5-3.7) | 0.493 | 0.22 (0.03-1.6) | 0.133 |

| Head/body louse infestation | ||||||

| No | 210 (83) | 40 (19) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 44 (17) | 10 (23) | 1.25 (0.6-2.7) | 0.577 | 1.06 (0.39-2.9) | 0.905 |

Among the 50 seroconverters for O. tsutsugamushi, 23 (46%) were symptomatic. Fever was the most common symptom (38%), followed by headache (14%) and increased irritability (4%), whereas rash, vomiting and diarrhoea were seen in two per cent individuals. A total of 27 (54%) seroconverters were asymptomatic and were considered as subclinical infections.

Discussion

In this study, a widespread seroprevalence of IgG antibodies to O. tsutsugamushi was observed among individuals screened from different villages in the Gorakhpur district. This indicated past exposure to O. tsutsugamushi and confirmed the endemicity of scrub typhus infection in this region. Significantly higher IgM and IgG seropositivity was observed during the peak AES period. Further, it was observed that IgM positivity was significantly higher in fever cases. Fever was also significantly high among seroconverted incident cases. Around one-fifth (19.7%) of the participants seroconverted during the AES epidemic period. Among the incident cases, more than half (54%) were asymptomatic, which indicated that scrub typhus infection was predominantly subclinical in this area.

It was noted that females had significantly higher antibody prevalence during both the surveys. This was probably due to the higher levels of exposure while handling grass and weed piles in the house, performing agricultural tasks and exposure to household rodents and shrews. Illiteracy was a risk factor identified for scrub typhus infection in this area16. The increased O. tsutsugamushi IgG seropositivity observed with age can be attributed to repeated and longer duration of exposure, a finding in concordance with various studies from India and from other parts as well6171819.

It was observed that O. tsutsugamushi seropositivity was associated with factors related to poor personal hygiene namely, not taking bath after work and not wearing footwear during outdoor activity. It has been reported that thorough scrubbing and washing of the body after mite exposure as well as use of protective footwear may decrease the risk of mite bites20.

Close contact with peridomestic animals was one of the significant risk factors observed in our study. Most participants in the survey reported of having close contact with animals in the form of bathing, feeding, milking and playing as they were residing in a rural area. These animals were infested with mites and acted as a transport host. In addition, rodents gets attracted to the food kept for these domestic animals, which, in turn, become host for the mites62122. Practice of open-air defecation is identified as an important predictor of both seroprevalent and seroincident O. tsutsugamushi infections during peak period23. People go out in fields, bushes, forests, river banks, or other open spaces for defecation and are exposed to vector bites.

The epidemic period of AES in Gorakhpur is during monsoons, which parallels to increase in O. tsutsugamushi prevalence, suggestive of meteorological conditions as a precipitating factor. Studies have related meteorological factors, especially rainy season, during which the behaviour of Trombiculidae is altered and relatively small numbers of chigger attachments are needed to infect potential hosts for scrub typhus24252627. Studies from north-east Himalayan region and Darjeeling district in India have revealed similar associations2829.

There is meagre literature pertaining to the kinetics of scrub typhus infection. The study from India showed a gradual decline in IgM antibody after infection and that it remained above the diagnostic threshold for about one year after infection. The IgG antibody levels peaked 10 months post-infection and remained above the cut-off level for more than three years post-infection. Studies have also reported peak IgG titres 2-3 wk after the onset of infection, indicating genetic/immunological variation between human populations or strain differences in different endemic regions303132.

Our study had certain strengths. It represented a large community serosurvey involving both adult and paediatric population. The seroincidence of O. tsutsugamushi infection was reported and incident cases were predominantly subclinical in nature. There is a need to investigate the reasons for the development of serious or fatal AES among a few cases of scrub typhus while most were mild or asymptomatic. However, there were limitations also. First, there was some potential for recall bias due to which data for all risk factor parameters could not be captured in all individuals. Seroincidence was worked out on the basis of the available 50 per cent of the population only. During the phase 2 survey, we were not able to achieve the required sample size.

In conclusion, our study showed that O. tsutsugamushi infection was endemic in this area. The infection was common in all age groups and associated with lower socio-economic status and poor personal hygiene. Its prevalence increased during AES epidemic period. O. tsutsugamushi infection should be considered one of the causes for fever morbidity in this area and treated accordingly to prevent the development of AES syndrome.

Financial support & sponsorship: This study was financially supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- DHR - ICMR Guidelines for Diagnosis & Management of Rickettsial Diseases in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:417-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus: Prevalence and diagnostic issues in rural Southern India. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1395-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus: An unrecognized threat in South India - Clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Trop Doct. 2010;40:129-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serological evidence of rickettsial infections in Delhi. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:538-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of scrub typhus at a tertiary care hospital in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:68-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus leading to acute encephalitis syndrome, Assam, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:148-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus and spotted fever among hospitalised children in South India: Clinical profile and serological epidemiology. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34:293-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute encephalitis syndrome following scrub typhus infection. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:453-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus meningoencephalitis, a diagnostic challenge for clinicians: A hospital based study from North-East India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6:488-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- First case of scrub typhus with meningoencephalitis from Kerala: An emerging infectious threat. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:141-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute encephalitis syndrome in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India - Role of scrub typhus. J Infect. 2016;73:623-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- AES: Clinical presentation and dilemmas in critical care management Gorakhpur scenario. J Commun Dis. 2014;46:50-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute encephalitis syndrome in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, 2016. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:1101-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Respondent Selection Methods in Household Surveys (October 25, 2013) Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies, Forthcoming. Available from: https://ssrncom/abstract=2392928

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of antibodies to rickettsiae in the human population of Suburban Bangkok. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:149-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibody prevalence and factors associated with exposure to Orientia tsutsugamushi in different aboriginal subgroups in West Malaysia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Climate variability, animal reservoir and transmission of scrub typhus in Southern China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005447.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors for scrub typhus in South India. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:576-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus in Japan: Epidemiology and clinical features of cases reported in 1998. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:162-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zoonotic infections in military scout and tracker dogs in Vietnam. Infect Immun. 1972;5:745-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ecological considerations in scrub typhus 1. Emerging concepts. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;39:209-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for acquiring scrub typhus among children in Deoria and Gorakhpur districts, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:2364-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meteorological factors and risk of scrub typhus in Guangzhou, Southern China, 2006-2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus incidence modeling with meteorological factors in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:7254-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- 1995. Tsutsugamushi disease: an overview. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press; Available from: http://trovenlagovau/work/15051803selectedversion=NBD12592635

- Scrub typhus in Darjeeling, India: Opportunities for simple, practical prevention measures. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1153-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of scrub typhus in the North East Himalayan region-Sikkim: An emerging threat. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:72-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of IgM and IgG antibodies after scrub typhus infection and the clinical implications. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;71:53-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A serosurvey of Orientia tsutsugamushi from patients with scrub typhus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:447-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics and magnitude of antibody responses against the conserved 47-kilodalton antigen and the variable 56-kilodalton antigen in scrub typhus patients. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1021-7.

- [Google Scholar]