Translate this page into:

Validity of Broselow tape for estimating weight of Indian children

Reprint requests: Dr Sandeep B. Bavdekar, Department of Pediatrics, TN Medical College & BYL Nair Charitable Hospital, Dr. AL Nair Road, Mumbai Central, Mumbai 400 008, Maharashtra, India e-mail: sandeep.bavdekar@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The Broselow tape has been validated in both ambulatory and simulated emergency situations in the United States and is believed to reduce complications arising from inaccurate drug dosing and equipment sizing in paediatric population. This study was conducted to determine the relationship between the actual weight and weight determined by Broselow tape in the Indian children and to derive an equation for determination of weight based on height in the Indian children.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India. The participants’ weights were divided into three groups <10 kg, 10-18 kg and >18 kg with a total sample size estimated to be 210 (70 in each group). Using the tape, the measured weight was compared to Broselow-predicted weight and percentage weight was calculated. Accuracy was defined as agreement on Broselow colour-coded zones, as well as agreement within 10 per cent between the measured and Broselow-predicted weights. The resulting data were compared with weights estimated by advanced paediatric life support (APLS) and updated APLS formulae using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results:

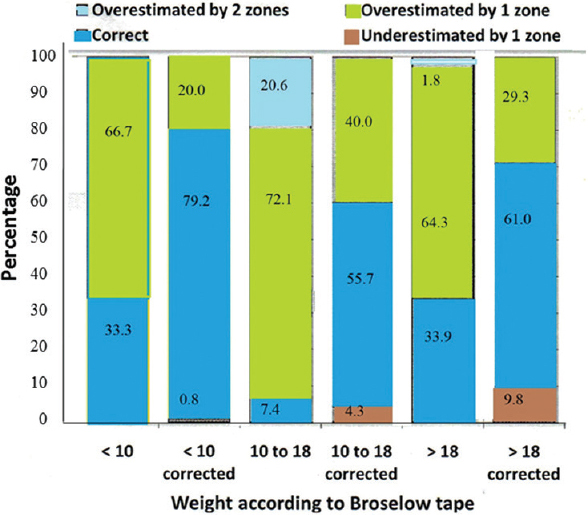

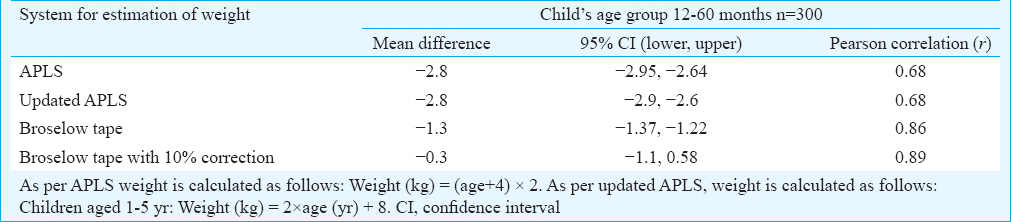

The mean percentage differences were −11.78, −17.09 and −14.27 per cent for <10, 10-18 and >18 kg weight-based groups, respectively. The Broselow colour-coded zone agreement was 33.3 per cent in children weighing <10 kg, but only 7.4 per cent in the 10-18 kg group and 33.9 per cent in the >18 kg group. Agreement within 10 per cent was 53.13 per cent for the <10 kg group, but only 21.08 per cent for the 10-18 kg group and 33.9 per cent for the >18 kg group. Application of 10 per cent weight correction factor improved the percentages to 79.2 per cent for the <10 kg category, to 55.70 per cent for the 10-18 kg group and to 61.0 per cent for the >18 kg group. The correlation coefficient between actual weight and weights estimated by Broselow tape (r=0.89) was higher than that between actual weight and weight estimated by APLS method or updated APLS formulae (r=0.68) in 12-60 months age group as well as in >60 months age group (r=0.76).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Broselow weight overestimated weight by >10 per cent in majority of Indian children. The weight overestimation was greater in children belonging to over 18 and 10-18 kg weight groups. Applying 10 per cent weight correction factor to the Broselow-predicted weight may provide a more accurate estimation of actual weight in children attending public hospital. Weights estimated using Broselow tape correlated better with actual weights than those calculated using APLS and updated APLS formulae.

Keywords

Anthropometry/instrumentation

body weight

medication errors/prevention

In contrast to adults, drugs are administered to infants and children on the basis of actual weight or surface area. When children present in a critical state, the caregivers are expected to provide instant care and administer drugs immediately. There is hardly any time to determine weight or height and calculate dosages of emergency drugs. In addition, when children present with shock or respiratory arrest or circulatory collapse, it may be necessary to carry out endotracheal intubation straight away. In such situations, various methods are used to determine the drug dosages and sizes of equipment: ‘guesstimates’ based on the child's apparent size or stature1, predicting it on the basis of length2, foot length3, age4 or a combination of above4. It can also be predicted using age-based formulae such as advanced paediatric life support (APLS) formula or updated APLS formula567. The Indian Academy of Pediatrics supported Paediatric Advanced Life Support Programme recommends that Broselow tape is used in such circumstances8. The Broselow tape recommends dosages of emergency drugs and preferred equipment sizes, on the basis of predicted weight, which, in turn, is estimated on the basis of actual height (height-weight correlation). Although the Broselow tape has been validated in both ambulatory9101112 and simulated emergency situations13 in the United States and is believed to reduce complications arising from inaccurate drug dosing and equipment sizing, but given the prevalence of malnutrition and consequent aberration in growth in Indian children it may overestimate the weight of these children.

Hence, this study was undertaken to determine the accuracy of weight measured by Broselow tape and compare it with the actual weight of Indian children. The findings of Broselow tape were compared with those obtained using APLS and updated APLS formulae.

Material & Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Paediatric Outpatient and Inpatient departments of BYL Nair ChariTable Hospital, a tertiary care public hospital attached to TN Medical College in Mumbai, India, over a period of 18 months from April 2012. The study was initiated after obtaining ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee and children aged 12-144 months were enrolled in the study after obtaining written informed consent from parents. If the prospective research participant was over seven years of age, his/her assent was also obtained before enrolment. Children were excluded from the study if they required immediate or emergency management or weighed over 35 kg or had height exceeding 145 cm.

Demographic data were collected from the parents or guardians. Age was determined based on documentary evidence or on the basis of birth date, birth year or age stated by the care-giver. The weight of children was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic weighing scale (IPA Devices Pvt. Ltd). The Broselow tape® (Armstrong Medical Industries, Lincolnshire, IL, USA) used for the estimation of weight based on the length has colour-coded segments depending on the weight estimated on the basis of length: grey (3-5 kg), pink (6-7 kg), red (8-9 kg), purple (10-11 kg), yellow (12-14 kg), white (15-18 kg), blue (19-22 kg), orange (24-28 kg) and green (30-36 kg). Each colour zone has dosages of emergency and premedication drugs, paralytic and induction agents and defibrillation written for children of corresponding estimated weights. For each child, the tape's colour code system was noted and compared. The data were recorded in a pre-designed proforma. Using the age provided by the caregiver, the child's weight was calculated using the APLS and updated APLS formulae567.

Usage of Broselow tape: To use the Broselow tape effectively, the child was made to lie down. While maintaining the position of the hand on the red portion at the top of the child's head, the free hand was used to run the tape down the length of the child's body until it was even with the child's heels. The tape that is level with the child's heels provided the child's approximate weight (kg) and the colour zone14.

Sample size: The sample size calculations were based on the study conducted by Ramarajan et al15. This study showed a consistent overestimate of the weight by the Broselow tape with a 10 per cent or more overestimation in children with >10 kg with an overall line of regression y=1.076x+0.27. At 5 per cent significance, 80 per cent power and assuming an f2 or effect size measure of 10 per cent, of weights between the two methods, and a single predictor variable, a sample size of 70 was calculated using an online regression calculator16.

Statistical analysis: Pearson's correlation was used for determining the association between predicted weights and actual weight and was followed by Bland-Altman plots17 to determine the mean bias and standard deviations (SDs) for the Broselow tape. The percentage difference between the Broselow-predicted weight and the measured weight was calculated as a measure of tape bias [100 × (measured weight - Broselow-predicted weight/measured weight)]. As per the null hypothesis the Broselow-predicted weight was equivalent to the measured weight if the 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) for the mean percentage difference included ±5 per cent. The SD of the percentage difference was also calculated to estimate tape precision.

To maintain consistency with previous literature on the Broselow tape, a Bland-Altman analysis was performed. This method combines bias and precision to determine upper and lower ‘limits of agreement’ by which the two methods differ. Accuracy of the tape was analyzed with respect to colour-coded zone prediction and weight prediction. First, percentage agreement on the same colour-coded zone by the Broselow tape and the measured weight, as well as percentage overestimation by one or two colour-coded zones, was calculated. Second, the number and proportion of times the Broselow-predicted weight was within 10 per cent of the measured weight was also determined15. Finally, a correction factor for the Broselow-predicted weight was derived by serially testing corrections until the accuracy within 10 per cent for each weight group was maximized. The correction factor was then tested by cross-validation against a random half of the sample as well as by linear regression. This correction factor was applied to the original Broselow-predicted weights, and the new corrected accuracies were obtained.

The Pearson's correlation coefficient was determined between the actual weight and the weights estimated using APLS and updated APLS formulae. For each of the above methods (weights estimated using APLS, updated APLS formulae and Broselow tape with or without 10% correction), the mean difference (the mean of differences between the actual weight and estimated weight and 95% CI) was computed using paired sample t test. The analysis was conducted using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

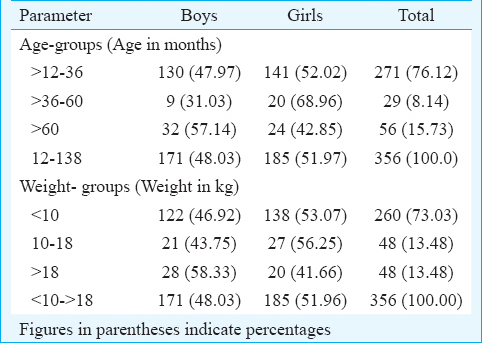

In this study, 356 children (age range: 12-138 month) were enrolled in the three groups (<10, 10-18, >18 kg). Girls accounted for 185 (52%) of the participants (M:F=1:1.08) and the maximum number of children were in the 12-36 months age group (271, 76%). The number of participants enrolled in each of the weight slabs is shown in Table I. During the study period, only 48 children each were enrolled in the weight groups of 10-18 kg and over 18 kg. The post hoc analysis showed that the power of the study was 65 per cent as a result of the actual number of participants enrolled. In the study, 135 (37.9%) participants [including 60 (32.43%) boys and 75 (43.85%) girls] had weight-for-age lower than −2SD.

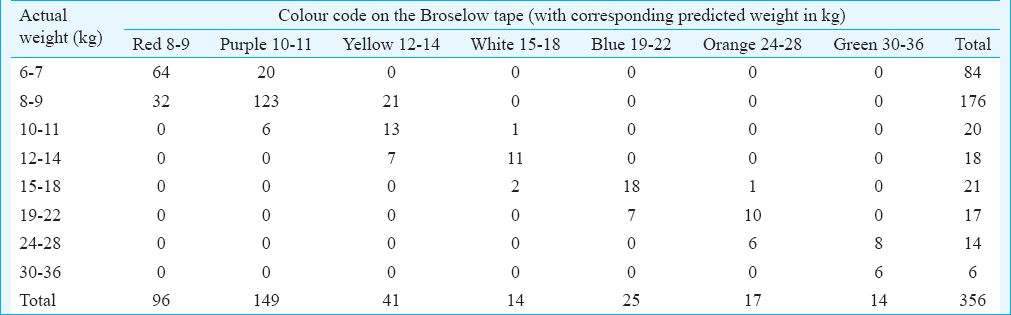

Table II shows the degree to which the actual weight bands matched with the Broselow tape weight bands. For example, weight of each of the 84 children in the weight range of 6-7 kg was overestimated: 64 (76.2%) of them were shown to be in the red (8-9 kg, overestimation by one colour) zone while 20 (23.8%) were shown to be in the purple (10-11 kg, overestimation by two colour) zone. The best convergence for colour zones was attained for 30-36 kg age group with all the six children in that weight group being shown to be in the corresponding green zone. For the 19-22 kg and 24-28 kg weight groups, the convergence was achieved in 7 (41.2%) and 6 (42.9%) children.

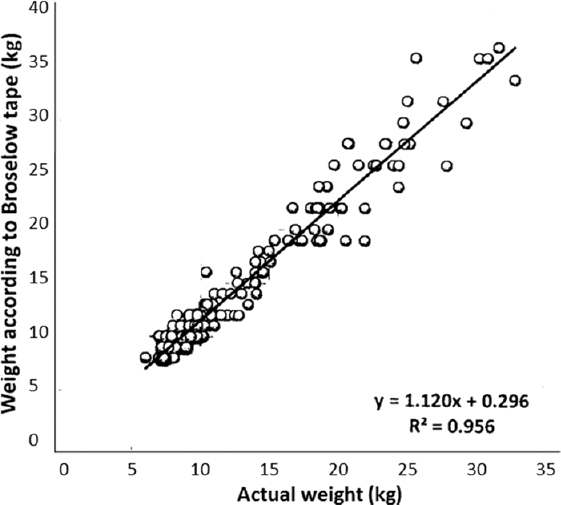

Bias and precision of the Broselow tape in the study population: Fig. 1 illustrates the Broselow-predicted weight for a given measured weight in the study population. There was a positive correlation between the actual weight and the Broselow tape estimated weight (R2=0.956; P<0.05). Fig. 1 also showed that the Broselow tape overestimated the weight. The crowding of data points for actual weights below 15 kg as compared to those above 15 kg indicated that the accuracy of Broselow tape estimated weights decreased with increasing actual weights.

- Correlation between Broselow tape-predicted weight and measured weight.

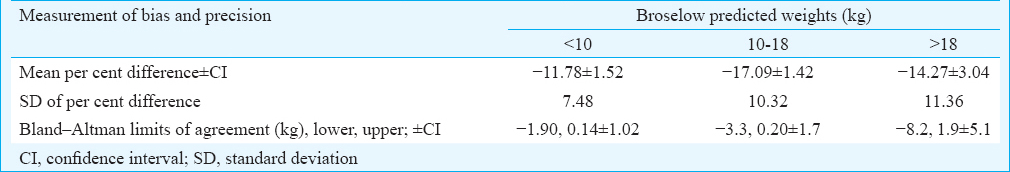

Table III shows the mean percentage difference between the Broselow-predicted weight and the actual weight. The mean percentage difference was significantly greater in the 10-18 kg (−17.09%) and the <10 kg (−11.78%) group (P<0.05).

The frequency of accurate colour-coded zone prediction and weight prediction within 10 per cent by the Broselow tape is shown in Table IV. Broselow tape had an accuracy of 33.3 per cent and 33.9 per cent in predicting the correct colour zone in the Broselow-predicted weight groups of <10 kg and over 18 kg. However, the corresponding accuracy in 10-18 kg group was only 7.35 per cent. After applying a 10 per cent correction factor, this accuracy improved to over 66 per cent in all the three weight groups.

After applying 10 per cent correction factor, the Broselow-predicted weights showed significant increase in the accuracy. The accuracy by colour code increased for all the three groups and reached 71.08 per cent for the <10 kg group. Fig. 2 shows the relationship of colour-code agreement before and after the application of 10 per cent correction. It was noted that in all the groups, the agreement of colour-codes increased after application of the 10 per cent correction, and in the 10-18 kg group, the overestimation by two colour codes vanished after this application. However, this resulted in underestimation of weight by one colour code in all the groups.

- Colour-coded zone agreement after 10 per cent correction.

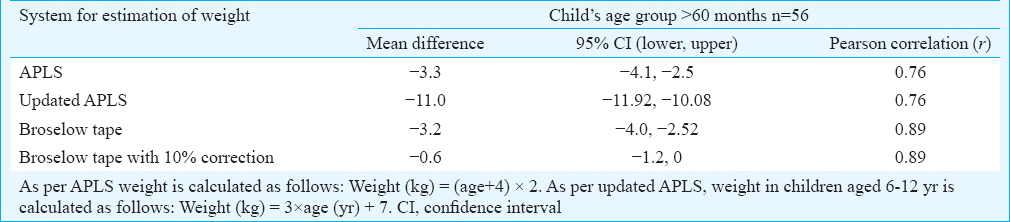

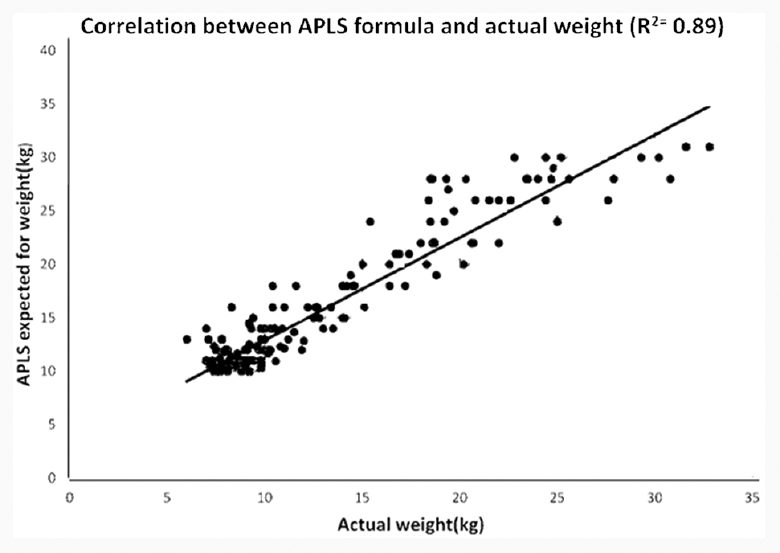

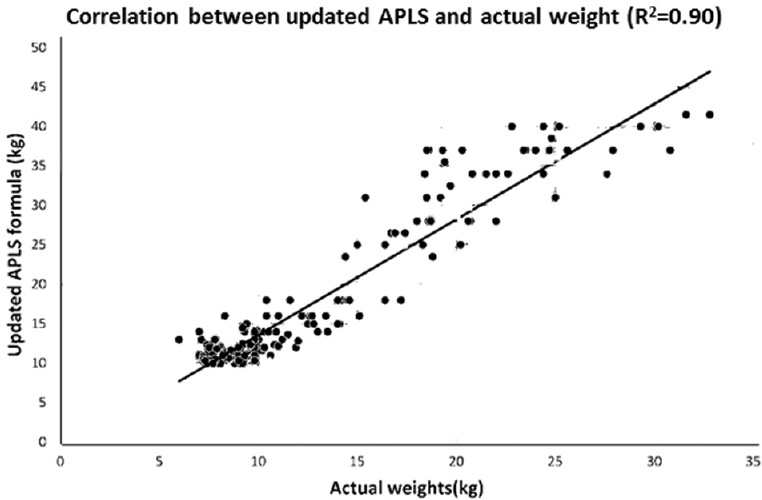

There was a positive correlation between Broselow and APLS method (r=0.68-0.89) with Broselow weight estimation having a strong correlation with the estimated weights (Table V). The mean difference in 12-60 months age group was −0.3 for Broselow weight estimation after 10 per cent correction as compared to −2.8 for APLS and updated APLS formulae. Similarly, in >60 months age group, the mean difference varied for Broselow tape - estimated weights with 10 per cent correction was −0.6. The corresponding Figures for APLS and updated APLS formulae were −3.3 and −11.0 (Table VI). The correlations between APLS and actual weight and that between advanced APLS and actual weight are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. These results showed that Broselow tape estimation with 10 per cent correction estimated weights were closer to the actual weight than those calculated with APLS formulae.

- Scatter graph showing correlation between Advanced Paediatric Life Support (APLS) and actual weight.

- Scatter graph showing correlation between updated Advanced Paediatric Life Support (APLS) and actual weight.

Discussion

This study showed that the weight predicted by the Broselow tape correlated well with the measured or actual weight. When judged on the basis of colour code accuracy, it matched only in 33.3, 7.4 and 33.9 per cent in <10, 10-18 and >18 kg weight groups, respectively. However, after 10 per cent correction was applied, the colour code agreement increased to at least 66 per cent of observations in all the weight groups.

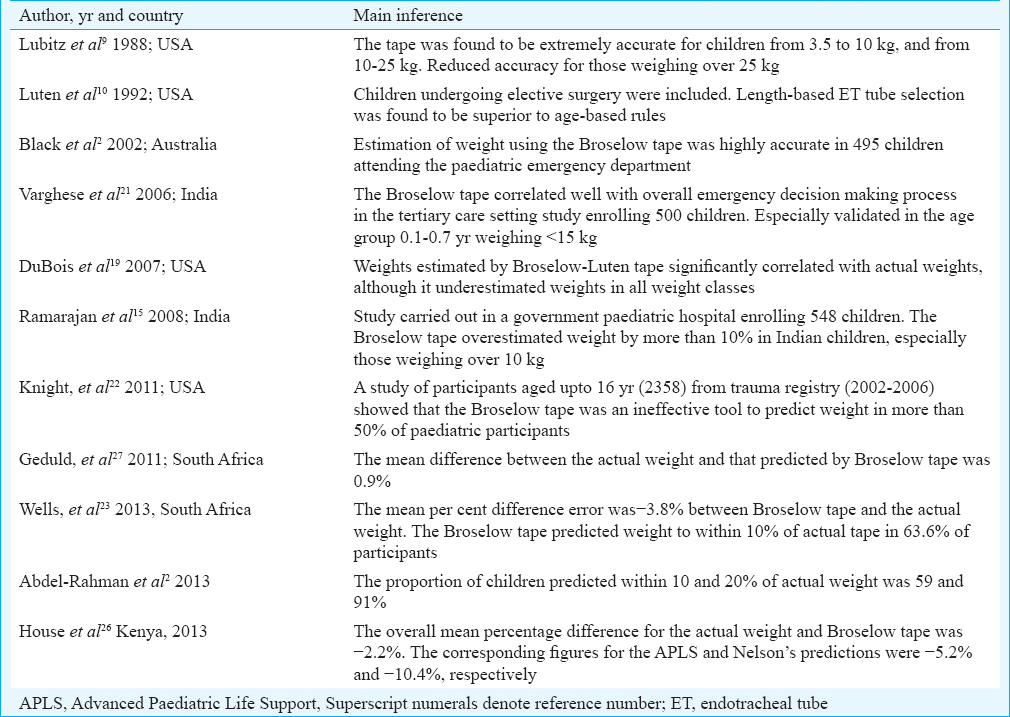

The Broselow tape was initially validated in the United States101819 and researchers in various countries2101518192021222324252627 have attempted to check if it is appropriate for their populations (Table VII). It seems appropriate that different populations check for the appropriateness of using the tape in their communities and at multiple intervals as nutritional status of children in their communities changes28.

An Indian study15 has concluded that the Broselow tape is not accurate in predicting weights in Indian children and that the accuracy of the tape improved to over 63 per cent after the application of a correction factor. Although our study had similar results, the accuracy determined in our study was lower. This marginal difference could be due to different population characteristics. Studies from Kenya26 and South African population2327 showed that Broselow tape-estimated weights were only marginally different from actual weights. This indicated that children in the present study had greater deviations from the Western standards, as compared to the Kenyan and South African populations enrolled in those studies232627. As proposed by House et al26, this could be attributed to greater frequency of childhood malnutrition in general and of severe malnutrition, in particular, in the Indian population.

Based on the findings of this study, it appears that use of Broselow tape without any modifications to Indian children would lead to administration of excessive doses. If the tape is to be used, modifications such as application of a correction factor or development of an indigenous tape based on local data would be helpful.

The findings of this study are applicable to children attending public hospitals in India. However, this can be confirmed by undertaking similar studies in other public hospitals in India with a similar patient profile. The data may not be applicable to children belonging to higher socio-economic groups, and those attending private healthcare facilities, as they have been shown to have growth patterns similar to those of children from the West2930. Lack of reliable age data of participants forced us to undertake analysis based on weight groups rather than age groups.

While comparing the estimation of Broselow as against the APLS formulae, the Broselow tape estimations were met with better accuracy as against the APLS formulae. Our study results are similar to those reported by Varghese et al21. However, Graves et al5 demonstrated that APLS formula was the most accurate method for age-based weight estimation in infants and found that in children over one year of age, the Best Guess formulae should be used. While Luscombe et al6 demonstrated that a single weight estimation (weight=3×age+7) was better at estimating weights, Ali et al7 opined that the APLS formula should be continued to be used as method of weight estimation.

Based on the study findings, it can be recommended that the Broselow tape cannot be used without modifications in Indian children attending public hospitals. As the application of 10 per cent correction factor to the Broselow-estimated weight increases the accuracy of the tape to over 60 per cent, this can be made use of in appropriate settings after these findings are validated in prospective studies.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Improving length-based weight estimates by adding a body habitus (obesity) icon. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:810-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the Mercy TAPE: Performance against the standard for pediatric weight estimation. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:332-9.e6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of weight of Indian children aged upto two years based on foot-length: Implications for emergency areas. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:125-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Can age-based estimates of weight be safely used when resuscitating children? Emerg Med J. 2009;26:43-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of actual to estimated weights in Australian children attending a tertiary children's'hospital, using the original and updated APLS, Luscombe and Owens, Best Guess formulae and the Broselow tape. Resuscitation. 2014;85:392-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Weight estimation in paediatrics: A comparison of the APLS formula and the formula 'Weight=3(age)+7' Emerg Med J. 2011;28:590-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is the APLS formula used to calculate weight-for-age applicable to a Trinidadian population? BMC Emerg Med. 2012;12:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric Advanced Life Support Group of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics. PALS guidelines 2000. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:872-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A rapid method for estimating weight and resuscitation drug dosages from length in the pediatric age group. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:576-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Length-based endotracheal tube and emergency equipment in pediatrics. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:900-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric endotracheal tube selection: A comparison of age-based and height-based criteria. AANA J. 1998;66:299-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of an intervention standardization system on pediatric dosing and equipment size determination: A crossover trial involving simulated resuscitation events. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:229-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Medical Services for Children Study packet for the correct use of the Broselow™pediatric emergency tape. Available from http://www.ncdhhs.gov/dhsr/EMS/pdf/kids/DEPS_Broselow_Study.pdf

- Internationalizing the Broselow tape: How reliable is weight estimation in Indian children. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:431-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Calculator Version 3.0 beta. Available from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc3/calc.aspx?id=1

- Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:135-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Broselow tape measurements versus physician estimations of pediatric weights. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:482-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of weight estimation methods for children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:227-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are methods used to estimate weight in children accurate? Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002;14:160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do the length-based (Broselow) Tape, APLS, Argall and Nelson's formulae accurately estimate weight of Indian children? Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:889-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is the Broselow tape a reliable indicator for use in all pediatric trauma patients?A look at a rural trauma center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:479-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The PAWPER tape: A new concept tape-based device that increases the accuracy of weight estimation in children through the inclusion of a modifier based on body habitus. Resuscitation. 2013;84:227-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new age-based formula for estimating weight of Korean children. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1129-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of three paediatric weight estimation methods in Singapore. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:E311-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the weight of children in Kenya: Do the Broselow tape and age-based formulas measure up? Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of weight estimation by age and length based methods in the Western Cape, South Africa population. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:856-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crosssectional growth curves for height, weight and body mass index for affluent Indian children 2007. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:477-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth performance of affluent Indian children is similar to that in developed countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:189-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS): Rationale, planning, and implementation. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(Suppl 1):S3-84.

- [Google Scholar]