Translate this page into:

Socio-economic correlates of bereavement among women - Examining the differentials on social axes

For correspondence: Dr Sanghmitra S. Acharya, Room No. 225, Centre of Social Medicine & Community Health, School of Social Sciences (SSS-2), Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110 067, India e-mail: sanghmitra.acharya@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Death, disease and disaster can inflict anyone, anywhere and at any time. While occurrence of such an event could be absolved of any selective strike, the outcome reflects otherwise. Historical deprivations experienced by certain populations have caused more bereavement and sorrow to them than those who have experienced lesser or no deprivation. Therefore, the process which shapes the factors to yield such a result is important and needs to be understood for any policy suggestions and programmatic inputs. Loss of pregnancy and newborn inflicts sorrow and bereavement across space, time and social labyrinth. The degree of bereavement is likely to reduce with time, but space and social context govern the response to it. Therefore, factors contributing to the differentials vary in their demographic, social and economic characteristics. The loss of pregnancy and newborn remains inadequately addressed. Family and community play a significant role in coping. While the developed countries have institutional structure to address coping with the loss, the South Asian countries rely heavily on the family and the community for such support. The present review examines these trajectories across social groups.

Keywords

Bereavement

early deaths

healthcare services

perinatal loss

pregnancy loss

social groups' differentials

Introduction

Loss of pregnancy and newborn inflicts sorrow and bereavement to the family and more on women. Family and community play a significant role in coping. Parity of pregnancy loss is important in governing the role of family and community in creating a coping mechanism. The present review endeavours to understand the situation of women who experience loss of child due to pregnancy loss or perinatal and infant death. It attempts to analyze the trends and patterns which evolve due to the social axes on which women are located and to provide an in-depth account of the local setting and contextualize it on infant and child mortality. It uses quantitative and qualitative methods to understand the factors attributing to the differential experiences of women belonging to different social groups in accessing services which prevent loss of foetus and child. How relevant is social background in influencing the bereavement experiences? Do demographic factors such as age and parity interplay with sociocultural factors to accentuate or aggravate bereavement? How does individual, family and community on one hand, and State agencies on the other, evolve the coping mechanism? Is there any State mechanism to address coping with bereavement? Secondary data sources have been analysed to find an answer which include National Family Health Surveys (NFHS-1, 2, 3, 4)1234 and a Multi-State study on social exclusion in multiple spheres undertaken by the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS), New Delhi (unpublished data).

Defining concepts

The concepts used to reflect on bereavement and sorrow include pregnancy loss, neonatal, perinatal and infant death5. A large numbers of children born to women, especially in developing countries, die soon after birth. Many of them live only up to four weeks succumbing to neonatal deaths. Among them, most die during the first week6. These are labelled as early neonatal deaths. Stillbirth is defined as ‘the birth of a baby after 24 wk gestation who did not show any signs of life after delivery’7. In the UK, one in 200 babies are born dead7. India accounted for 22.6 per cent of the global burden of stillbirths in 20158.

A large proportion of infants are alive when labour starts, but they die due to complications arising during birth. The perinatal period commences at 22 completed weeks (154 days) of gestation and ends seven completed days after birth. The neonatal period begins with birth and ends 28 complete days after birth. Neonatal deaths are divided into early neonatal deaths, occurring during 0-6 days of life, and late neonatal deaths, occurring during 7-27 days of life5. The infant deaths are defined as those occurring between 0 and 1 yr of age5. These demographic events lead to bereavement. These are also likely to stigmatize the women and open options of artificial reproductive technology (ART) including surrogacy. Bereavement includes the experience of family members and friends besides the bereaved persons, in its entirety from the pregnancy loss or early death and subsequent adjustments for continuing to live.

Policy environment

Health policies and programmes in almost all developing countries have emphasized on mother and child and acknowledged their needs. Reproductive health services embedded in India's National Family Welfare Programme are deeply rooted in the concern with population growth. In fact, promotion of mother and child health has been the most important objective of the family welfare programme of India and has been evident since the first five-year plan (1951-1956)1. As a part of Basic Needs Programme initiated during the Fifth Five Year Plan (1974-1979)1, maternal and child health and nutrition services were integrated with family planning services as part of this first Population Policy. Since then, the thrust has been to provide at least a minimum level of public health services to pregnant women, lactating mothers and pre-school children. However, the support of bereavement arising out of early deaths does not form a part of any policy including the Health Policy of 201749. There has been a continuous reluctance to recognize the needs of women belonging to vulnerable groups, and the issue has remained marginalized in the policy agenda. Thus, bereavement becomes additionally painful for these women.

Caste-based social structure has excluded dalits from access to resources, schemes and services10. They have remained backward in education, livelihoods and opportunities to live a life with dignity. This continues to affect their health. The Joseph Bhore Committee Report (1946)9 pointed towards the inequitable access to resources which resulted in health status differentials across social groups. Providing healthcare access to the vulnerable population groups is the responsibility of the State. All the more when the financial burden of curative care is higher among economically vulnerable, most of whom are Dalits10.

To address early deaths, the India Newborn Action Plan (INBAP) was launched in 201411. Six interventions were proposed to reduce the number of stillbirths by a third by 2025 and also maternal and neonatal deaths9. Also a mechanism was proposed to track the stillbirths. The stillbirth has not been considered as a public health issue in India due to lack of its recognition at a policy or community level1213.

In India, productive and reproductive phases of life begins early. The 2011 Census data show that the median age at the time of marriage, although has increased across all social groups and genders, female population continues to be in adolescent ages at the time of marriage3. The median age for men increased to 23.5 yr in the 2011 Census, from 22.6 yr in 2001; as against 19.2 yr and 18.2 yr for women in the respective years3. This exposes them to family building process early in life and for longer duration. This demographic phenomenon influences women of different social groups differently and requires psychosocial approach to understand health inequalities14. While the debate between psychosocial, economic and demographic views have been central in the scientific discussion around health inequalities, a more integrative approach is needed to understand the nuance of social identity-based differentials. The social gradient in poor health is likely to be the result of psychosocial factors in interaction with economic conditions as much as identity-based denial from access to health resources. Therefore, there is a need to advance from the binary of psychosocial and economic factors to an integrated model of the life circumstances, comprising both the psychosocial and material factors.

Conceptual framework

The emphasis on maternal and child health has been to ensure uncomplicated pregnancy and safe delivery. Women from the vulnerable groups are often unable to access the maternal and child health services. Sensitivity towards the vulnerable women, availability of providers and services, will enhance access. Institutions have to consciously work towards creating enabling environment for utilization of maternal and child health services. Enabling environment for vulnerable populations needs to be designed through policies and programmes and infusing sensitivity among the providers and co-users of the resources and services15.

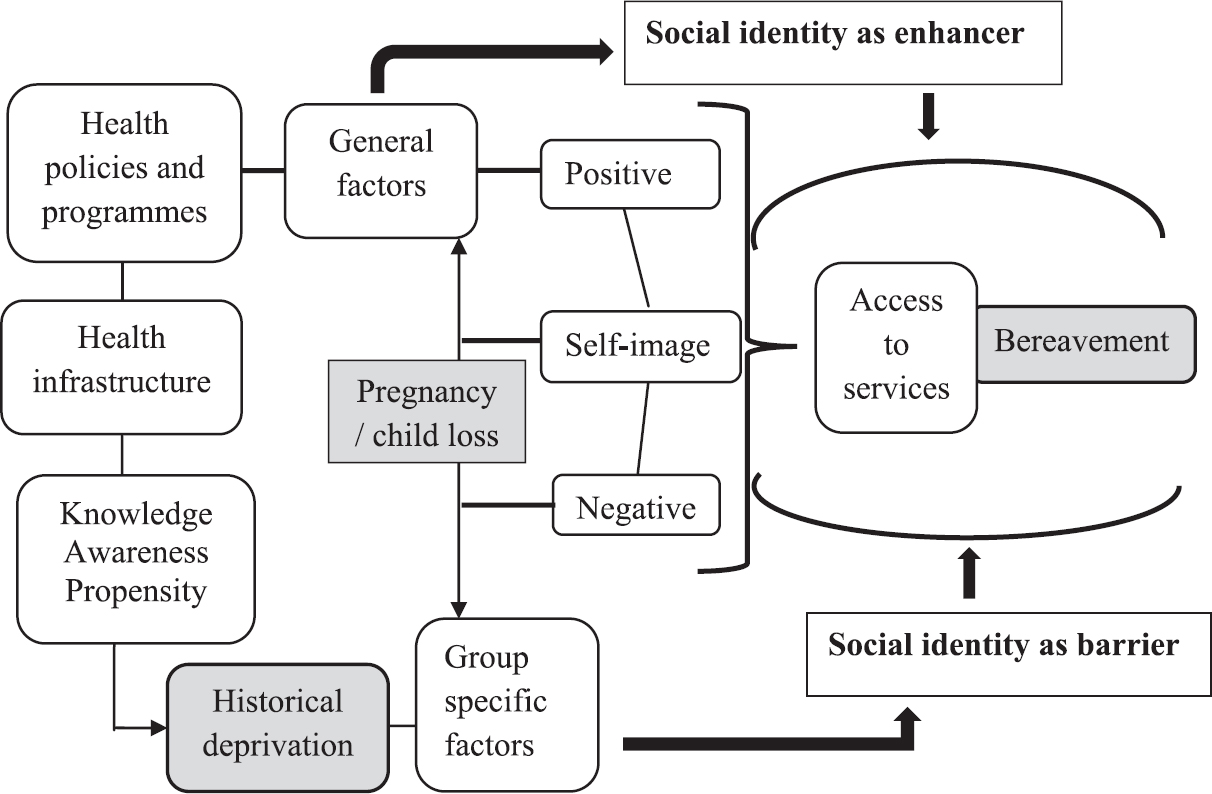

Inequalities in child health vary across socio-economic groups in terms of health outcomes, access to health services and utilization of health services. Disparities exist in utilization of services as much as the differential pace of economic and social development and distribution of the benefits of development along with the inadequacy of the public healthcare systems to deliver equitable health services16. Thus, the argument that addressing economic disparities will eventually take care of social inequalities needs to be revisited. There is an inherent discord in this framework. Gender and economic factors are amply illustrated and argued. Caste-based determinants and consequences of deprivation and denial are not adequately illustrated in the context of maternal and child health and well-being. Caste-based predictors have mostly been seen from the lens of socio-economic indicators. Emphasis has been on income disparities while social identities have remained marginalized. Access, availability and perception of self lead to utilization of services. Access translates into utilization through the web of adequate resources, conducive policy regime and providers’ sensitivity to social heterogeneity as a factor of differential access; and perception of self16. Access is the function of awareness, information, knowledge and encouraging setting to use them and proclivity to overcome inhibitions and impediments for interacting with providers and institutions. Lack of appropriate opportunities and mechanisms to access opportunities for education and income-generating activities result in poor living conditions including housing, health, nutrition, lifestyle and social environment. Availability of resources is dependent on the procurement chain. Policy environment, market and marketing, media and advertisement, motivation and buying capacity of the users collectively impact the demand-supply cycle of resources and thus their availability. How an individual creates self-image has elements of the image created (of the individual) by the others. Thus, created positive images enhance confidence and check inhibitions. Thus, utilization of resources and services is determined by three factors - access, availability and perception of self16 (Figure).

The bereavement caused by early deaths such as neonatal deaths and stillbirths are embedded in poor maternal and child health and inadequate care during pregnancy, child birth and post-pregnancy, as much as it is in the differential access to services. Management of complications during pregnancy and delivery; hygiene during delivery and the first critical hours after birth and newborn care require appropriate skilled management. Access to these services is differently manifested across social groups. Recurrent early deaths and foetal loss often lead to stigmatizing of women and open the choice of surrogacy and other form of assisted reproductive technology.

Concern for early deaths

Pregnancies and childbearing are affected by gender sensitivity. Status of women, their nutritional status and age at the time of conception are crucial elements. Frequent, too early and too late pregnancies; poor cord care; discarding colostrum and feeding other food are some sociocultural factors which influence early deaths3. Neonatal deaths are caused mostly when the babies are severely malformed, born prematurely and suffer from obstetric complications before or during birth17. They have difficulty adapting to extrauterine life, and harmful practices after birth often contribute to infections. All this is closely related to the impoverished status of the mother.

Low birth weight also contributes to neonatal deaths. Nearly 15 per cent of the newborn infants weigh <2500 g globally. While in the developed countries, only 6 per cent weigh <2500 g; in some parts of the world, this proportion is more than 30 per cent17. Weight at birth, complications at birth and neonatal health are an outcome of maternal health and nutrition at conception and during pregnancy. If infections such as malaria and syphilis are contracted during pregnancy, then adverse pregnancy outcomes like mortality are observed18. The stillbirths are not only a demographic event but a socioemotional incidence causing bereavement for the mother and the family. Therefore, they deserve to be noticed and attended by the society and the healthcare system particularly in developing countries1920.

The perinatal mortality is a strong indicator of the health status of pregnant women, mothers and newborns. Perinatal mortality reflects on maternal health and nutrition and the quality of obstetric and paediatric care available21. Perinatal mortality levels are used by the policymakers to recognize the problems, track the trends and disparities, which can be used for assessing changes in large public health environment. Social and cultural factors influence parity and the outcome of a birth. However, as societal norms change with development and technological advancement, hope of ‘good life’ and ‘medical care’ reduces parity and replaces home deliveries. However, access to the ‘good medical care’ is more often than not, restricted to some as evident in the differential health outcomes across social groups1822. Advancement in reproductive health, quality of obstetric and neonatal facilities and upward economic gradient can yield reduction in neonatal deaths and stillbirths23.

Maternal, perinatal and neonatal survival requires appropriate technologies to address critical medical problems. It also requires a programme that attends to the healthcare needs of the woman and her baby throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. This mandate needs to be executed at the primary care level for all pregnant women and at higher levels of secondary and tertiary care for women and babies with complications without any form of discrimination. This will address the needs of nearly half of the world's women who still give birth at home2425 in the absence of any skilled care provider26. There are also structural deficiencies in providing safe childbirth and newborn care. The absence of healthcare providers, outdated knowledge and inadequate skills, lack of essential medicines, supplies and equipment, overcrowding and inadequate hygiene are to name a few27.

Social groups and early mortality differentials

Understanding the differentials across social groups depends largely on reliable data on relevant indicators. Perinatal and neonatal mortality data can be obtained from vital registration, sample registration or community level microstudies. Reliable vital registration is available for only about one-third of the world's population28. At least 85 per cent reporting of both completeness and coverage of mortality is considered as reliable by the WHO. The United Nations, however, requires 90 per cent or more completeness of adult and infant mortality for considering the data reliable27. Surveys are the main source of data for developing countries. The NFHS data suggest that like most other indicators of social and economic well-being, neonatal and infant mortality is more among the scheduled caste (SC) as compared to the high caste (HC) denoted as ‘Others’ administratively, despite having improved over the time since NFHS-1 was conducted during 1992-93 to NFHS-4 during 2015-16 (Table I). While there is a consistent improvement in early deaths from 1992 to 2016, the gap between the SC and HC continues to persist.

| Social groups | Neonatal mortality rates (per 1000 livebirths) | Infant mortality rate (per 1000 livebirths) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFHS-1 | NFHS-2 | NFHS-3 | NFHS-4 | NFHS-1 | NFHS-2 | NFHS-3 | NFHS-4 | |

| SC | 63.1 | 53.2 | 46.3 | 33.0 | 107.6 | 83.0 | 66.4 | 45.2 |

| ST | 54.6 | 53.3 | 39.9 | 31.3 | 90.5 | 82.2 | 62.1 | 44.4 |

| OBC | ‑ | 50.8 | 38.3 | 30.5 | ‑ | 76.0 | 56.6 | 42.1 |

| Others | 50.6 | 40.7 | 34.5 | 30.4 | 82.2 | 61.8 | 48.9 | 40.9 |

| Total | 52.7 | 47.7 | 39.0 | 29.5 | 86.3 | 73.0 | 57.0 | 40.7 |

Why the continued disparity? Illustrations from live data

If the disparities continue despite the continuous efforts of the State, it is imperative to examine the alternatives. How are the efforts translated into programmatic initiatives comprising services and resources which can be accessed by the vulnerable populations like the SC? Participation of people (policymakers, providers, etc.) involved in the process of translation is extremely important. Whether participation of such people is perceived as routine work and therefore, should be done mechanically without any sensitivity towards the population for whom it is meant; or participation to ensure with utmost sincerity that the programmatic initiatives reach the people for whom they are meant. Differential access results in varying bereavement. In case of neonatal and infant deaths, information dissemination may be done by the grassroots level workers mechanically devoid of any concern for the people. This would entail no efforts for dissemination of the information and counselling. Service may be provided to fulfil the ‘target’ more than to enhance health. In another situation, there can be adequate and timely dissemination followed by provisioning to the people who need and should be provided. This differential in rendering of services results in the experience of bereavement and sorrow which, therefore, differs from one social group to the other. Cooley's theory of 'self’ works towards creating specific 'self-image’18. A mother from HC has an image of assertion, smaller family size and therefore, the value attached to each newborn and the infant is different than that of a mother from the SC who is constantly stereotyped with large family size, high mortality among newborns and infants and consequent high fertility and lesser ‘luxury’ of mourning the loss in case it occurs.

Differential treatment by the health service providers and co-users

The differential treatment is often observed when no, less or wrong information is provided; discriminatory treatment at the place of delivery of care; involuntary inclusion or exclusion from some schemes; discriminatory treatment during emergency and not entering the house of the care user during the home visits and behaviour and attitude of the provider towards the care service users. It may also be observed in the inequality in care provisioning at the healthcare centre by the providers - doctor and the supporting staff and at home during the visit by the health workers such as accredited social health activist (ASHA), auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) and anganwadi worker (AWW)29. Differential treatment by service providers can also be experienced during diagnosis, dispensing of the medicine, laboratory tests, while waiting in the health centre for consultation and while paying the user fees30. The co-users of the services can use the services out of their turn. Their behaviour and attitude can be derogatory towards some, dominating and suppressing them. They may overlook the rules to use the services when it is actually due to the people from the discriminated groups31.

Emotional problems caused due to perinatal loss affect overcoming the loss and adjusting during bereavement period. There is denial and feeling of being shattered expressed by the bereaved parents especially the mothers32. Experience of perinatal loss makes the parents feel sad and low, and in need of support. Therefore, perinatal loss needs to be acknowledged as an inimitable loss to parents, especially mothers, and others need to be sympathetic and thoughtful and provide emotional support to them32. Response to the grief experienced due to losing a baby by miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death is fairly similar33. If antenatal diagnosis suggests risk of physical or mental abnormalities in the foetus, the mother has the option of termination of pregnancy34. In such cases, parents tend to experience bereavement associated with their decision35. Experience of bereavement is aggravated after termination and causes post-miscarriage distress.

Recurrent loss and bereavement

Loss of pregnancy also entails bereavement due to stigma associated with childlessness which often drives towards new medical technologies collectively called as ART such as in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for instance36. Fertility preservation is yet another method37. About 40 to 80 per cent women cancer patients and about 30-70 per cent of men cancer patients may become sterile after treatment for cancer,38 and therefore, fertility preservation often becomes an option for them to ensure family building. Experience of sorrow is more among women. Sorrow and grief gradually diminish with passage of time since the occurrence of loss, good spousal intercommunication, social support and a subsequent pregnancy.

Surrogacy has been a practice to address childlessness; and also, therefore, related to bereavement. Surrogacy in India39 was legalized in 2002. However, the practice and conduct of surrogacy are in need of a regulatory mechanisms40. Most of the women who chose to be surrogate mothers in India come from humble background. By accepting to be a surrogate mother, when not philanthropic, they earn, on an average, a sum which exceeds the annual household income manifolds41. Surrogacy is affected by a number of factors such as cost of infertility, facilities for travel across countries and importantly, the socio-economic conditions of the families of the women who choose to be surrogate mothers. The decision to be a surrogate mother often relies on the intrafamily communication as it requires staying away from family during the period of gestation. The rights of the surrogate mother are dependent on the terms and conditions of the commissioning health facility or provider. Power differentials between them and the health facility functionaries or provider and poorly framed legal safeguards make the surrogate mother vulnerable42. The risk of multiple pregnancy and foetal reduction is common to ensure higher success rate. Women are often given little information regarding the risks involved43. The choice of the number of embryos to transfer and the mode of delivery is made neither by the surrogate nor the commissioning parents. In the fast-growing market of commercial surrogacy and opacity in clinical ethics, need for devising of regulative law for reproductive ethics to ensure that the interests of surrogate mothers are safeguarded is an important concern4142.

Bereavement care

A mother experiences physical and emotional postnatal reactions after the loss of the baby through markers such as vaginal bleeding, lactation, stitches or caesarean scar. Appropriate relief and postnatal care becomes imperative for the bereaved mothers. While western countries have fairly adequate medical support system, in India, the support is likely to come from the family. In many cases, particularly in South Asia, a death child in often not talked about. In census count and surveys also, unless probed, information about deceased infant and children is not divulged2728.

In most developed countries, parents whose baby has died are encouraged to keep photos, toys and clothes of the baby for memory. In some countries, such as Scotland, most of the maternity hospitals have provision for capturing the photographs through digital cameras44. While such pictures are considered good for memory making, they are also likely to prolong bereavement. Therefore, personalized care and support at each stage following the loss of the baby is important. In case of multiple births, the loss of one or more than one can be more difficult to overcome. Furthermore, sorrow for the lost one(s) is likely to be visible alongside the concern for the vulnerable survivor(s)45. It can be a peculiar stress as a living child's developmental stages may consistently remind of what could have been the situation if the loss has not occurred.

Like the regular antenatal and postnatal care, in case of pregnancy and perinatal loss, the health workers should provide the mothers with appropriate care and support to the affected parents to cope with perinatal loss. Parents may be encouraged to share their grief and reflect on their perception on perinatal loss to enable relevant interventions by the heath workers46. Providing psychosocial support is important because psychological reactions invariably accompany a pregnancy loss4748. Therefore, there is a need for greater awareness and sensitivity among healthcare providers, counsellors, nursing staff and medical social workers about the psychological impact of loss. Healthcare providers need to spend extra time with the affected couples to understand their feelings and find out solutions for their grief outside the biomedical framework. They are required to be empathic, sensitive and supportive of couples faced with this type of loss4748.

Consequences of loss and coping strategies

Miscarriage and perinatal loss are known to cause psychosocial distress. It is well recognized that one-fifth of the pregnancies result in miscarriage leading to depression and anxiety323334. Nearly half of the women experiencing loss due to miscarriage suffer from psychological morbidity in subsequent months after loss374546. A substantial proportion of women who suffer the loss of a child develop a psychological disorder. Most studies have concentrated on loss and very little has been studied about the experience of miscarriage4748.

Emerging evidence suggest that loss due to miscarriage is associated with psychological consequences. Psychological morbidity due to miscarriage needs to be addressed as postpartum depression, both medically and para-medically. It is evident that women who experienced loss due to miscarriage desired psychological intervention46. More studies in this area are needed to corroborate the results yielded till now.

Care for the mother and newborn

Available and accessible care for the mother and the newborn are very important factors which influence pregnancy loss and early deaths. Given the differentials in the socio-economic status and access to care, health outcomes vary across social groups. In a multi-state study (unpublished data) to examine issues of social exclusion in multiple spheres, disparity in healthcare given to the newborn was evident. It varied across social groups. A broad disaggregation as SCs and HCs of the study population was used for the analysis.

A large proportion of perinatal and neonatal deaths can be averted if appropriate and adequate care, both medical and health, can be made available for access2628. More than 49 per cent newborn among SC need to be given medical care as compared to 43 per cent among HC(unpublished data). Thus, there is a likelihood that due to poor economic conditions leading to poor health, need to attend to the new mothers from the SC was higher than those from the HC. While not much difference is evident in the care given before discharge, after discharge, there is a reversal of share of medical care in favour of the HC 95 per cent as against 93 per cent for SC(unpublished data). Although postnatal care is important for both the social groups, HC received better service delivery than that of their SC counterparts(unpublished data). Similar differential was visible for immunization also (unpublished data). Being a universal programme, all children should receive the benefit equally. However, the evident differential point towards factors such as providers’ sensitivity to reach out to the underserved is important. A shift in favour of the HC is likely to originate due to the stereotypes based on social identity. The decrease in the share of the children immunized as the age advances is also reflective of the general disadvantage experienced by both SC as well as HC. However, the shares consistently remaining lesser for the SC than HC suggest specific disadvantage to this group in accessing immunization services (unpublished data). Fewer children among SC as compared to HC have been immunized for all the vaccines and oral intakes - BCG, DPT, Polio, MMR, measles and vitamin A. Immunization services provided across social group reveals that there is a variation between SC and HC (unpublished data).

Among the service providers, ANM is responsible for immunization and dissemination of information about immunization. Most of the BCG is being provided by ANM. The gap, however, between SC and HC was 10 per cent points. The doctors in the public and private health facilities; nurses; paramedical staff like ANM, pharmacist, lady health worker and the primary level workers such as anganwadi worker (AWW) and ASHA - all of them have provided the immunization services to a comparatively larger proportion of HC as compared to SC except for ANM who have provided these services to 10 per cent more SC (82.71%) than HC (72.71%) (unpublished data). A plausible explanation could be that they targeted to complete vis-à -vis children from specific social groups; SC children were less accessed for this compared to HC, and the latter might have access to other sources than the ANM. Many a times, the services cannot be used as well as provided because of various reasons ranging from cost, customs and time to fear of vaccination. Noteworthy is the fact that the most reasons affect both the groups with almost similar intensity. Despite that, the gap was evident in favour of the HC.

An enquiry was made in same villages of western India. This reflected that services were provided but apathetically to 37 per cent SC as against 29 per cent HC. Furthermore, more than one-fourth of the former had to wait before any service was provided to them as compared to about 22 per cent HC. Thus, it was found that more number of SC respondents were either served apathetically or served after long waiting than that of their HC counterparts. More than 19 per cent HC respondents felt dissatisfied due to the absence of the service provider and only 13 per cent SC respondents have stated it as the main reason for dissatisfaction. It was noted that 9.68 per cent HC respondents stated that the service was available but not provided while only 6.21 per cent SC respondents gave this cause(unpublished data).

Some of these issues have been corroborated by the large-scale data such as the NFHS. The financial hindrance affected access of more than 20 per cent among the SC and about 13 per cent among the HC. When the provider was not available, about 27 per cent SC were affected in terms of getting the services, while this share was about eight per cent among the HC. Similarly, distance obstructed 24 per cent SC and about 18 per cent of HC in accessing the services (Table II). It was of concern to note that these problems were affecting more women in 2015-2016 as compared to 2005-2006.

| Social groups | Getting money for treatment | Distance to health facility | No provider available | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 2015-2016 | 2005-2006 | 2015-2016 | 2005-2006 | 2015-2016 | |

| SC | 20.4 | 30.1 | 27.3 | 32.5 | 23.9 | 46.3 |

| ST | 31.2 | 35.1 | 44 | 42 | 35.2 | 54.9 |

| OBC | 16.4 | 23.7 | 26 | 29.4 | 23.2 | 43.9 |

| Others | 12.9 | 20.8 | 8.5 | 24.2 | 18.2 | 42 |

| Don’t know | ‑ | 34.7 | ‑ | 38.5 | ‑ | 45.8 |

| Total | ‑ | 25.4 | ‑ | 29.9 | ‑ | 44.9 |

ST, scheduled tribe; SC, scheduled caste; OBC, other backward caste

Source: Ref. 3

On the basis of the empirical evidences, availability of care was dependent on the presence of health personnel and the supply of medicines and equipment for diagnostic tests etc. Distance and infrastructure are also important. These, however, are the factors which affect all. There are specific factors which are embedded in the prejudices and stereotypes associated with the understanding of caste. A typology of issues and the processes evolving differential bereavement have been proposed in Table III.

| Factors | Causes | Solutions | Bereavement |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||

| Availability of care | Absenteeism of personnel; inadequate/irregular drug supply | Accountability of personnel, adequate and regular supply | Hopelessness |

| Distance | Inappropriate panning | Provision of means and modes of transportation | Helplessness |

| Infrastructure | Delay in supplies; inadequate personnel; instruments, space and structures | Routine supply chain; filling of vacancies; supply of state of art equipment; provide space/building | Plausible hope |

| Caste specific | |||

| Considered unclean, less informed/less educated; deserve low-quality services, need not be given | Poor or no sensitivity; biases; prejudices; poor socio-economic status leading to stereotyped image | Sensitization of the providers; other activities for livelihood, support for activities currently engaged in (especially the ‘dying customary vocations’ such as weaving) | Helpless and dejection |

| Restricted use of services due to holding the camps in the dominant caste areas | Power relations between dominant and nondominant castes are favourable to the former influencing the service provision; dominant caste is endowed with resources and the infrastructure to provide the services | Support, facilitate and encourage the providers for locating the services in nondominant group locality | Plausible hope |

| Despite claims of being sensitive, there are evidences of discrimination being practiced | Historically instituted biases and prejudices influence the understanding of ‘sensitivity’ | Historical biases and prejudices need to be tackled through a robust mechanism; leadership; re-interpreting power relationships; questioning current hierarchy and inculcating assertion and preparedness for consequences of assertion | Sensitive questioning |

Summing up

Perinatal loss due to miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth and neonatal death is an experience of grief for couples and their family members. Perinatal loss causes grief which affects everyone associated with the loss. Acceptance and response to such loss reflect evident gender differences. The studies related to expression of grief following pregnancy loss was reviewed to understand the factors affecting experience of grief. It was found that most studies were done in developed countries. A large percentage of women experienced grief at loss of foetus, infant and young children. Very often, they felt guilty and depressed. Women with no living children were more predisposed to severe grief reaction.

Barriers to access to healthcare services were apparent in refusal to observe certain norms considered compulsory in providing care but were often infringed while providing care to the care seekers from vulnerable communities. The health camps for immunization, especially when located in places inaccessible to dalits; and when information was disseminated with prejudice, led to differentials access. The gap in access between SC and HC women was the outcome of prejudices which excluded SC women partially or completed from access to maternal and child health services. Therefore, sensitivity of the service providers and their concerns for the vulnerable populations was relevant in ensuring utilization of services. The policy, organizational structures and the service providers should be sensitive to the concerns of the vulnerable populations. If a provider does not inform about a certain scheme launched for the vulnerable groups, barriers such as inhibitions aggravate their inability to utilize the scheme. On the contrary, a sensitive provider is likely to inform about the schemes and programmes without any discrimination, creating the enabling environment for accessing the schemes and programmes for utilization and accruing benefits and overcoming the inhibitions. This sensitivity is likely to arise out of the providers’ alignment with biases and stereotypes related to the vulnerable populations. Therefore, mapping of diverse populations in understanding their experience of loss, coping mechanism and interventions following a loss is imperative.

Financial support & sponsorship:

None.

Conflicts of Interest:

None.

References

- International Institute for Population Sciences. In: National Family Health Survey (MCH and Family Planning), 1992-93: India. Bombay: IIPS and ORC Macro; 1995.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. In: National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2, 1998-99: India. Mumbai: IIPS and ORC Macro. Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) In: National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. Mumbai, India: IIPS and Macro International; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) In: National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16, India. Mumbai: IIPS & ICF (formerly Macro International); 2017.

- [Google Scholar]

- Support around Death. Pregnancy Loss, stillbirth and neonatal death. Available from: http://www.sad.scot.nhs.uk/ bereavement/ pregnancy-loss-stillbirth-and-neonatal-death/

- United Nations Children's Fund. In: Every Child Alive: The urgent need to end newborn deaths. New York: UNICEF; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e98-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Health Portal. Bhore Committee, 1946. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/bhore-committee-1946_pg

- Oppression and denial: Dalit discrimination in the 1990s. Econ Polit Wkly. 2002;37:572-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Child Health Division. In: India Newborn Action Plan. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- 3.2 million stillbirths: Epidemiology and overview of the evidence review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist J, Marmot M, eds. Social inequalities in health. New evidence and policy implications. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. :272.

- Universal health care: Pathways from access to utilization among vulnerable populations. Indian J Public Health. 2013;57:242-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conceptualizing social discrimination in access to health services towards measurement- illustrating evidences from Villages in Western India. Indian Emerg J. 2011;6:14-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund, World Health Organization. In: Low birth weight: Country, regional and global estimates. New York: UNICEF; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. In: Optimal feeding of low-birthweight infants: Technical review/Karen Edmond, Rajiv Bahl. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reproductive pattern, perinatal mortality, and sex preference in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: Community based, cross sectional study. BMJ. 1997;314:1521-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Birth counts: Statistics of pregnancy and childbirth. Vol 1. London: HMSO; 2000.

- World Health Organization. Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme. In: Perinatal mortality: A listing of available information, (WHO/FRH/MSM/96.7). Geneva: WHO; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health status and access to health care services - Disparities among social groups in India. Working Paper Series. Vol 1. New Delhi: Indian Institute of Dalit Studies; 2006.

- The decline in child mortality: A reappraisal. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1175-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi-country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why women choose to give birth at home: A situational analysis from urban slums of Delhi. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004401.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2005. Skilled attendant at birth - 2005 global estimates. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/ globalmonitoring/skilled_attendant.html

- Million Death Study Collaborators. Maternal mortality in India: Causes and healthcare service use based on a nationally representative survey. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83331.

- [Google Scholar]

- Department of Evidence, Information and Research and Maternal Child Epidemiology Estimation. In: MCEE-WHO methods and data sources for child causes of death 2000- 2016. Global Health Estimates Technical Paper WHO/HMM/ IER/GHE/2018.1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Health Mission. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Available from: https://rch. nhm.gov.in/RCH/

- Caste and patterns of discrimination in rural public health care services. In: Blocked by caste- economic discrimination and social exclusion in modern India. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. :208-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Access to maternal and child health care: Understanding discrimination in selected slums in Delhi. In: Acharya SS, Sen S, Punia M, Reddy S, eds. Marginalization in globalizaing Delhi: Issues of Land, Livelihoods and health. New Delhi. India: Springer; 2017. p. :327-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- The experiences of mothers who lost a baby during pregnancy. Health SA Gesondheid. 2007;12:3-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Miscarriage as a traumatic event: A review of the literature and new implications for intervention. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:235-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility Preservation in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1994-2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, correlates and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in the pregnancy after stillbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:556-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social, ethical, medical & legal aspects of surrogacy: An Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140(Suppl 1):S13-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women in poverty turning to surrogacy. Borgen Magazine. Available from: http://www.borgenmagazine.com/womenpoverty- turning-surrogacy/

- [Google Scholar]

- Clipping the stork's wings: Commercial surrogacy regulation and its impact on fertility tourism. Indiana Int Comp Law Rev. 2016;26:336-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- From intercountry adoption to global surrogacy: A human rights history and new fertility frontiers. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2017.

- Transnational commercial surrogacy in India: Gifts for global sisters? Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:618-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of previous perinatal loss on subsequent pregnancy and parenting. J Perinat Educ. 2002;11:33-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myles textbook for midwives 2003

- Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:229-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Grief intensity, psychological well-being, and the intimate partner relationship in the subsequent pregnancy after a perinatal loss. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44:42-50.

- [Google Scholar]