Translate this page into:

Association of increased risk of asthma with elevated arginase & interleukin-13 levels in serum & rs2781666 G/T genotype of arginase I

For correspondence: Dr Krovvidi S. R. Sivasai, Department of Biotechnology, Sreenidhi Institute of Science & Technology, Ghatkesar, Hyderabad 501 301, Telangana, India e-mail: ksrsivasai@sreenidhi.edu.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

High expression of arginase gene and its elevated level in serum and bronchial lavage reported in animal models indicated an association with the pathogenesis of asthma. This study was undertaken to assess the serum arginase activity in symptomatic asthma patients and healthy controls and to correlate it with cytokine levels [interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13] and arginase I (ARG1) gene polymorphism.

Methods:

Asthma was confirmed by lung function test according to the GINA guidelines in patients attending Allergy and Pulmonology Clinic, Bhagwan Mahavir Hospital and Research Centre, Hyderabad, India, a tertiary care centre, during 2013-2015. Serum arginase was analyzed using a biochemical assay, total IgE and cytokine levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and genotyping of ARG1 for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs2781666 and rs60389358 using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method.

Results:

There was a significant two-fold elevation in the arginase activity in asthmatics as compared to healthy controls which correlated with disease severity. Non-atopic asthmatics showed elevated activity of arginase compared to atopics, indicating its possible role in intrinsic asthma. Levels of serum IL-13 and IL-4 were significantly high in asthma group which correlated with disease severity that was assessed by spirometry. A positive correlation was observed between arginase activity and IL-13 concentration. Genetic analysis of ARG1 SNPs revealed that rs2781666 G/T genotype, T allele and C-T haplotype (rs60389358 and rs2781666) were associated with susceptibility to asthma.

Interpretation & conclusions:

This study indicated that high arginase activity and IL-13 concentration in the serum and ARG1 rs2781666 G/T genotype might increase the risk of asthma in susceptible population. Further studies need to be done with a large sample to confirm these findings.

Keywords

Atopic

cytokines

genetic polymorphism

haplotype

non-atopic

severity

Studies on animal models and human asthma cases revealed that the enzyme arginase plays an important role in airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR)12345. Arginase probably suppresses the generation of nitric oxide (NO), a bronchodilator by limiting the availability of arginine to NO synthase6. Utilization of arginine by arginase leads to the production of ornithine, putrescine, proline and spermidine, which are involved in collagen synthesis, mucus production, cell proliferation and differentiation16. Low generation of NO and increased arginase metabolites may lead to AHR and bronchoconstriction7.

Kochański et al8 first reported elevated levels of arginase in the sputum of individuals with bronchial asthma; however, its relevance and significance were not established until 2003 when Zimmermann et al1 identified high expression of novel candidate genes arginase I (ARG1), arginase II and cationic amino acid transporter-2 in two different murine models sensitized with two different allergens. Further studies in animal models such as guinea pig and mice using different allergens revealed an increase in the levels of arginase and its association with disease development2345. In the murine model, ARG1 gene expression was upregulated ten folds upon ovalbumin challenge and was downregulated with the treatment of a new drug, R142571, indicating the role of arginase in asthma pathogenesis9. Studies in human asthmatics further established the function of arginase in pathogenesis of asthma based on the high levels of arginase expressing cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid1 and elevated levels of arginase in the sputum8 and serum7. Although different groups correlated high levels of arginase with asthma71011, there are limited reports substantiating the same from India.

Th2 cytokines, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 play a crucial role in the inflammation of airway. Studies on animal models of asthma1 and cell lines12 demonstrated that these cytokines have significant effect on induction of ARG1. Wei et al13 reported the induction of ARG1 by IL-13 and IL-4 mediated through cAMP and JAK/STAT6 pathway in the rat aortic smooth muscle cells. In the murine model for asthma, Yang et al14 demonstrated that IL-13-induced AHR was attenuated by the inhibition of ARG1 activity through interference of RNA. The unique relationship between Th2 cytokines and arginase levels, particularly in airway inflammation, was not fully established in the human system. The current study was designed to address the impact of IL-13 and IL-4 cytokines on arginase levels/activity in the serum.

Various reports on the association of genetic variants with asthma1516 and response to certain anti-asthmatic drugs1718 in different population suggest that polymorphisms in the arginase gene influence the risk to asthma and atopy1516. However, the effect of polymorphism on arginase functional activity was not well established. In the present study, two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (rs2781666 and rs60389358) of ARG1 gene, which are located in the promoter region were assessed for the role in the expression of arginase in symptomatic asthma patients and healthy controls.

Material & Methods

Symptomatic randomly selected asthma patients (n=150), attending the Allergy and Pulmonology Clinic, Bhagwan Mahavir Hospital and Research Centre, Hyderabad, India, during the period 2013-2015, were enrolled based on the GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) guidelines (www.ginasthma.org) after confirmation by lung function test. Age-matched healthy individuals (n=150) without respiratory complications and family history of asthma and allergy were randomly selected from our laboratory, students and general administrative staff and included them as controls for the study. Patients were randomly selected based on the availability at the clinic. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee. Written and informed consents were obtained from participants to be a part of this observational study. The patients were categorized into groups based on total serum IgE levels and lung function test [forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)]. Total serum IgE levels were used as surrogate marker for atopy; based on this, the patients were subgrouped into atopic asthmatics who have ≥325 IgE IU/ml (n=74) and non-atopic asthmatics who have <325 IgE IU/ml (n=76)19. The patients were subgrouped based on severity using lung function test (spirometry) according to the GINA guidelines. Those having FEV1 ≥80 per cent of predicted with asymptomatic with peak expiratory flow (PEF) <20 per cent were labelled as intermittent (n=54); FEV1 80 per cent, symptomatic, with PEF between 20 and 30 per cent as mild persistent (n=37); FEV1 60-80 per cent as moderate persistent (n=18) and FEV1 <60 per cent as severe persistent (n=41). Detailed demographic data of the patients characteristics are given in Table I. The mean age of the asthma patients was 34±6 yr and for healthy controls was 41±7 yr with a range of 17-60 and 21-57 yr, respectively. Fifty six asthma patients and 68 healthy controls were male and 94 asthma patients and 82 healthy controls were female. Ten millilitres of peripheral venous blood was collected from each participant for obtaining serum and DNA from cells.

Serum arginase assay: Serum arginase assay was performed in 100 patients and 100 controls using QuantiChrom™ Arginase Assay Kit (Bioassay systems, Hayward, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, serum samples were incubated in a substrate (arginine) buffer and manganese solution for two hours at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of urea reagent and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The final product urea (which indicates the activity of arginase) was read at 520 nm in a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, USA). Arginase activity was determined by the formula: optical density (OD) of sample − OD of blank/(OD of standard − OD of water)×10.4 and expressed in units/l. One molar urea solution was used as standard.

Serum cytokine assay: Serum IL-4 and IL-13 levels were assessed in 100 patients and 100 controls by sandwich ELISA using eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA) reagent kit. Briefly, capture antibodies for IL-4 and IL-13, respectively, were immobilized on 96-well flat plates (cat#3590 Corning USA) and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing, a blocking buffer was added and incubated for one hour to avoid non-specific bindings. Standards were serially diluted and 100 μl each of standards and samples were added to the respective wells and incubated at 4°C for two hours. Plates were washed and 100 μl of detection antibody was added to all wells and incubated further for an hour, followed by the addition of avidin tagged to horse radish peroxidase enzyme. Wells were washed before addition of 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate and the colour change was visualized after stopping the reaction with 2 N H2SO4. Change in colour was measured at 450 nm in a Bio-Rad microplate spectrophotometer and the OD was observed to be directly proportional to cytokine concentrations. Using MPM 6.0 (Bio-Rad) software, the final concentrations of cytokines were determined.

Genotyping of arginase I (ARG1) gene by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP): Peripheral blood (2 ml) from 150 participants in each group was collected and the DNA was isolated using a Flexigene DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration (OD at 260 nm) and purity (OD 260/OD 280) were determined using an ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Genotyping was performed using PCR-RFLP method. PCR was used to amplify 233 bp of ARG1 gene encompassing rs2781666 [(G/T) at −864 position] and rs60389358 [(C/T) at −866 position] loci using sequence-specific primers 5’-TCAGGGGCATAGAGGTTGAC-3’ and 5’-TACCATGTGTCCGATGCAGT-3’. The primers were designed using Primer3 software20. The PCR mixture consisted of MgCl2 (1.5 mM), standard concentrations of dNTPs (1 mM) and Taq polymerase (1 U/reaction), specific primers (10 pM) and template DNA (100 ng), and the samples were subjected to 35 cycles. The protocol followed for PCR was pre-denaturation for four minutes at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 45 sec at 94°C, then annealing for 45 sec at 58°C, followed by an extension for 45 sec at 72°C and a final extension at 72°C for seven min after 35 cycles.

The amplified PCR products were subjected to restriction digestion with HpyCH4IV and BsrD1 restriction enzymes for rs2781666 and rs60389358 positions, respectively. The digested products were visualized in three per cent agarose gel under ultraviolet rays by gel documentation system (Bio-Rad XR+, USA). The genotypes were determined based on the restriction enzyme-digested DNA fragments of different sizes. Digestion of ARG1 gene by HpyCH4IV restriction enzymes results in product size of 233 bp for homozygous GG, 116 bp and 117 bp for homozygous TT and 233 bp, 116 bp and 117 bp for heterozygous GT genotype for rs2781666 SNP. Similarly, for rs60389358, SNP digestion with BsrD1 restriction enzyme generated 233 bp for homozygous CC genotype, 120 and 113 bp products for homozygous TT genotype and 233, 120 and 113 bp products for heterozygous CT genotype. The RFLP results were validated in some cases where randomly selected 50 PCR amplicons were outsourced for sequencing (Bioserve Ltd., Hyderabad, India).

Statistical analysis: Unpaired t test was applied to compare two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc test Bonferroni multiple comparison was used for comparing more than two groups. Spearman's correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between arginase and cytokines. The genotype analysis was performed using dominant, co-dominant, recessive and over-dominant models by logistic regression corrected by age and sex in SNPstats software (https://www.snpstats.net/start.htm)21. The allelic frequencies were compared by Chi-square test. A 2×2 cross-tabulation method was used to determine odds ratio (OR) with 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) by open Epi software; Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health software (Version 2.2.1, Emory University and Rollins School of Public Health, GA, USA). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test and haplotyping was done using Haploview software22.

Results

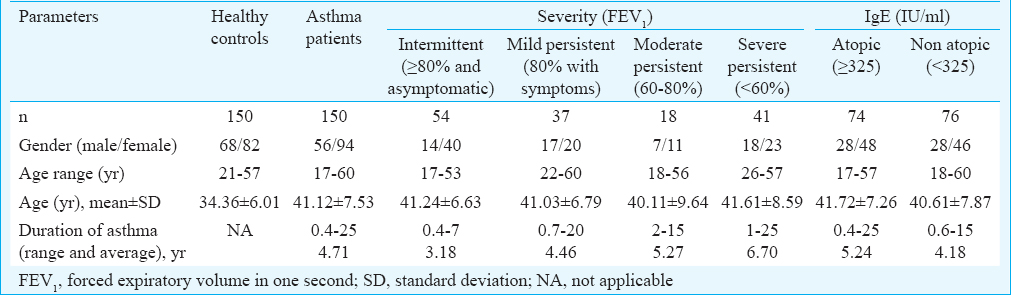

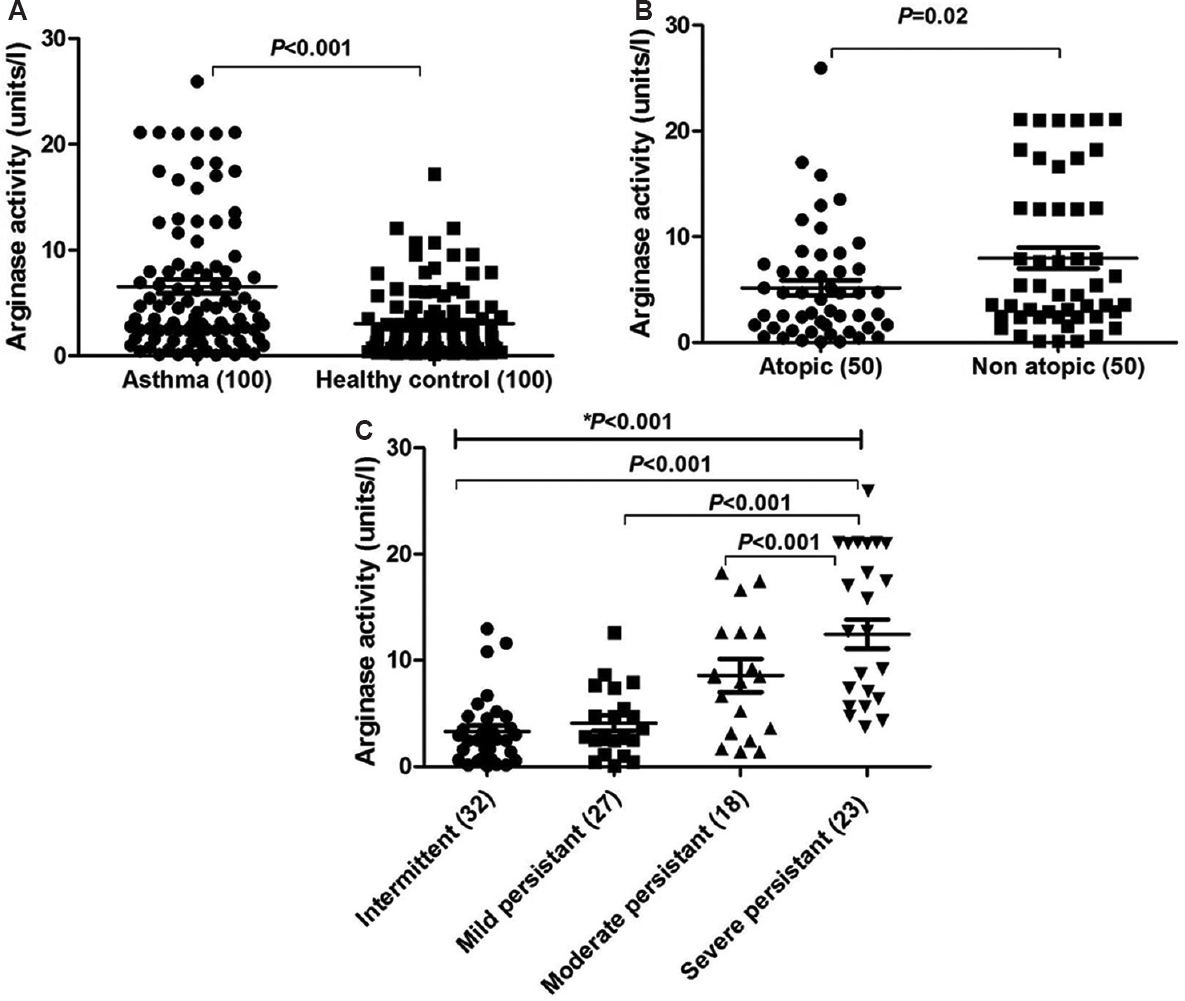

Elevated serum arginase activity correlated with severity of asthma: Arginase activity was found to be significantly (P<0.001) elevated (2-folds) in asthma patients compared to healthy controls with a mean±SE of 6.57±0.63 and 3.04±0.33 units/l, respectively (Fig. 1A). The non-atopic group had significantly (P=0.02) higher arginase activity compared to that of the atopic group (7.97±1.0 vs 5.16±0.73 units/l; Fig. 1B). Analysis between arginase activity and severity of the disease indicated a positive correlation. Arginase activity was compared between stratified groups based on severity which was found to be significant (Fig. 1C). The arginase activity was observed to be 3.34±0.60 units/l in intermittent persistent asthmatics. This was lower but not significantly different from the mild persistent asthmatics (3.70±0.57 units/l) and moderate persistent (8.08±1.36 units/l) groups. However, severe persistent asthma group (13.38±1.56 units/l) significantly varied from intermittent, mild and moderate persistent groups (Fig. 1C).

- Serum arginase activity. (A) Comparison between asthma patients (n=100) vs healthy controls (n=100). (B) Comparison between non-atopic asthmatics (n=50) vs atopic asthma patients (n=50). (C) Comparison between groups based on severity of the disease. Numbers of subjects assessed in each group are shown in parentheses. *One-way ANOVA P value obtained for overall groups.

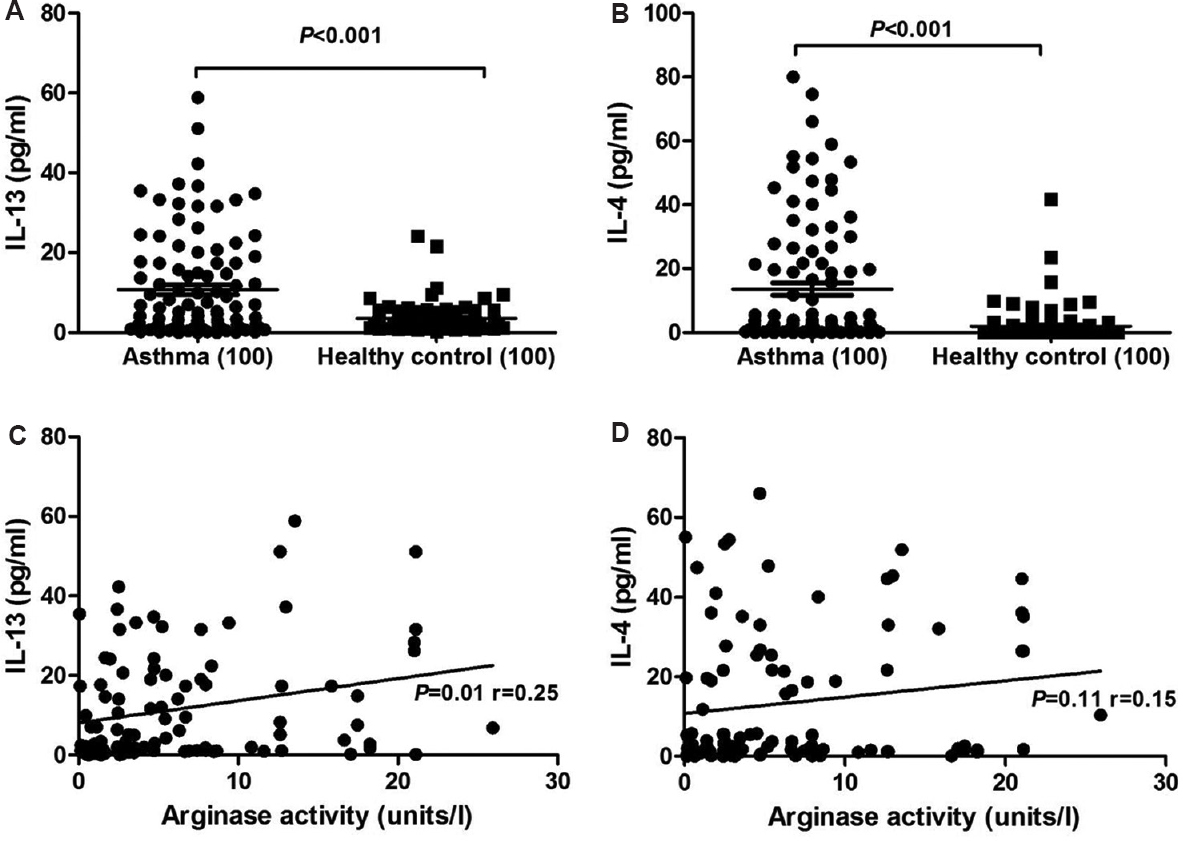

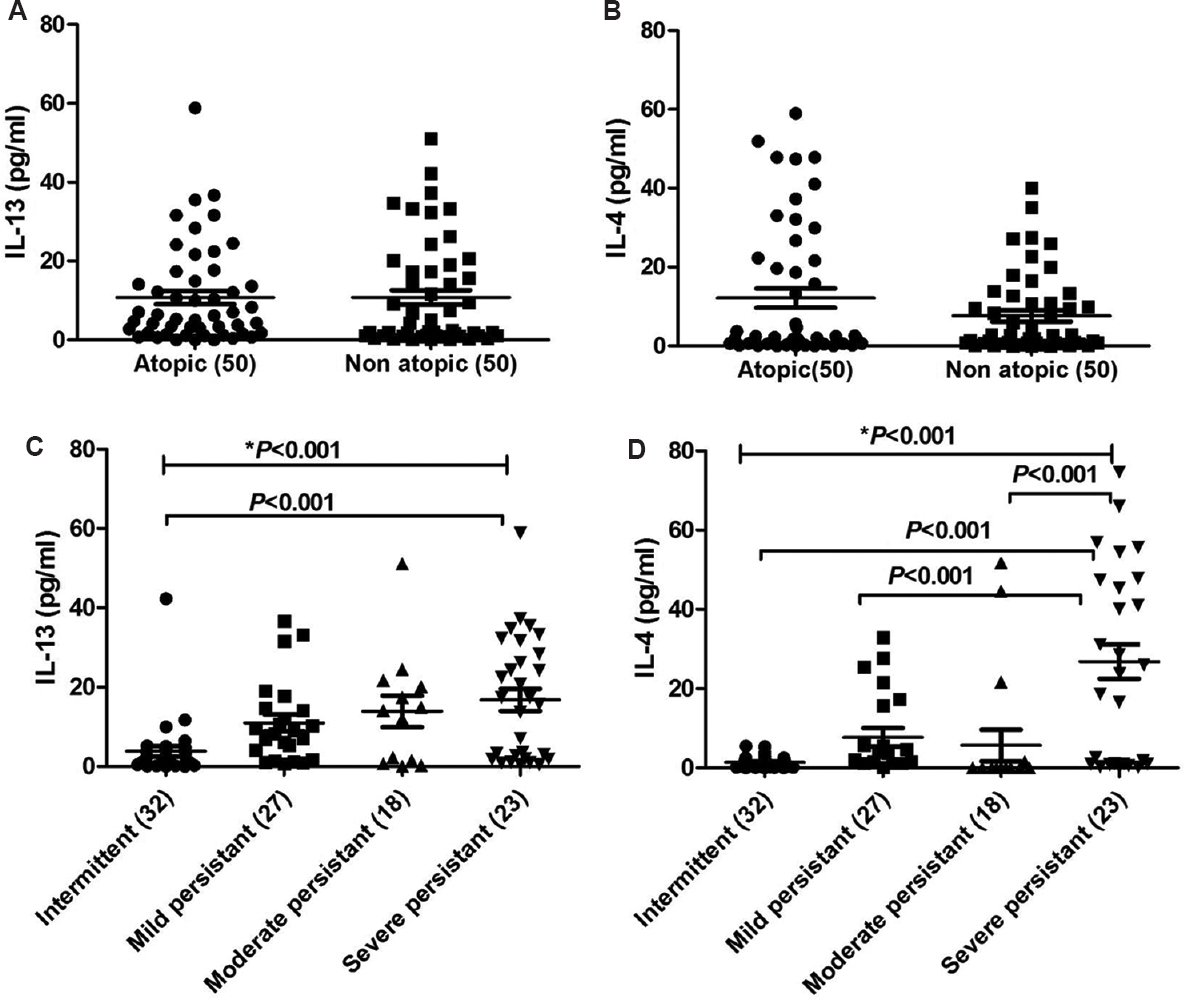

Correlation of arginase activity with elevated serum interleukin-13 (IL-13): Serum cytokine levels of IL-4 and IL-13 were elevated in asthmatics compared to healthy controls with a mean of 13.62±1.92 vs 1.93±0.52 pg/ml for IL-4 and 10.77±1.27 vs 3.54±0.34 pg/ml for IL-13 as shown in Fig. 2A and B, respectively. The differences between the groups were significant (P<0.001)for IL-4 and IL-13 cytokines. Elevated IL-13 levels positively correlated (r=0.25) with elevated arginase activity which was significant (P=0.01) (Fig. 2C); however, similar correlation could not be observed with IL-4 (P=0.11) (Fig. 2D). Analysis among atopic and non-atopic asthmatics revealed no variation in IL-13; however, IL-4 was high in atopic asthmatics when compared to non-atopics even though the difference was not significant with a mean±SE 12.15±2.44 and 7.6±1.41 pg/ml, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). IL-13 and IL-4 levels were increasing with the severity of the disease from intermittent to severe persistent asthma patients (Fig. 3C and D). Even though the IL-13 levels were elevated from intermittent persistent to severe persistent asthmatics, significant variation was observed only between intermittent and severe persistent asthma (3.58±1.35 and 18.75± 3.33 pg/ml; P<0.001) (Fig. 3C). The IL-4 levels were observed to be 1.45±0.25 in intermittent persistent asthmatics. The levels were lower than but not significant from mild persistent (8.12±2.17 pg/ml) and moderate persistent asthmatics (9.23±5.09 pg/ml). Significantly (P<0.001) elevated levels of IL-4 were observed in severe persistent group (30.33±5.01 pg/ml) when compared to intermittent persistent (1.45±0.25 pg/ml), mild persistent (8.12±2.17 pg/ml) and moderate persistent (9.23±5.09 pg/ml) asthmatics (Fig. 3D).

- Levels of interleukin (IL)-13 and IL-4 cytokines in serum. (A) IL-13 levels in patients vs controls, (B) IL-4 levels in patients vs controls, (C) correlation analysis between IL-13 and serum arginase levels, (D) correlation analysis between IL-4 and serum arginase. P values and correlation coefficient (r) are depicted.

- Levels of interleukin (IL)-13 and IL-4 in serum of patients. (A) Comparison of IL-13 levels between atopic vs non-atopic asthma patients, (B) comparison of IL-4 levels between atopic vs non-atopic asthma patients, (C) comparison of IL-13 levels between groups based on severity of the disease, (D) comparison of IL-13 levels between groups based on severity of the disease. Numbers of subjects assessed in each group are shown in parentheses. *One-way ANOVA P value obtained for overall groups.

Distribution of arginase I (ARG1) genotypes, alleles and haplotypes among asthmatics and control groups

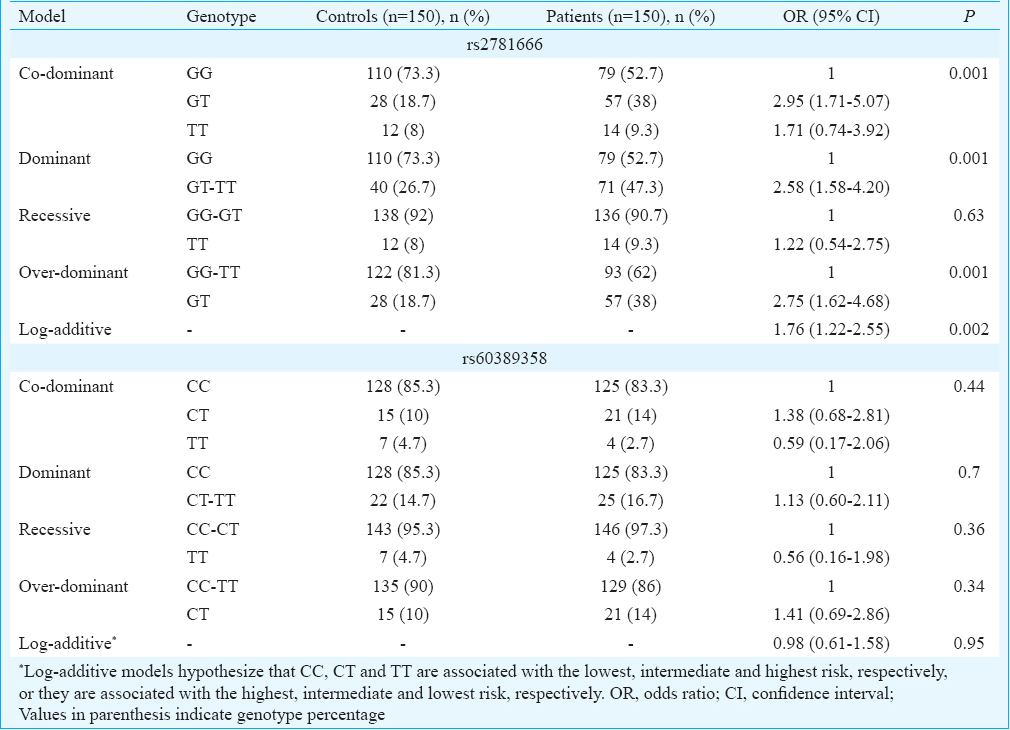

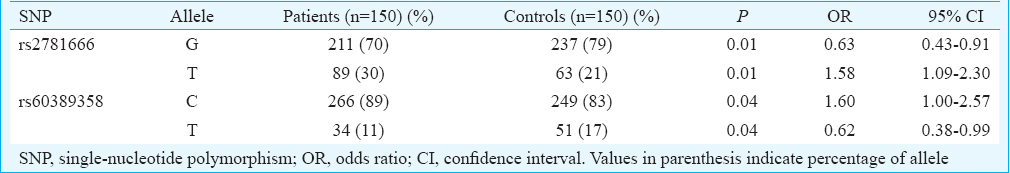

rs2781666: The over-dominant, dominant and co-dominant models of rs2781666 (G/T at −864 position) gene polymorphism were found to be significantly associated with asthma (Table IIA). The over-dominant model indicated a higher frequency of GG-TT genotypes in healthy controls with an OR of 2.75 (CI 1.62-4.68, P=0.001), indicating negative association with asthma by conferring the resistance. An association was observed with GT and TT genotypes with OR of 2.58, suggesting that higher risk in dominant model (CI 1.58-4.20, P=0.001) for asthmatics indicates the susceptibility to the disease. The frequency of GT genotypes was significant in asthma with OR of 2.95 (CI 1.71-5.07, P=0.001) indicating association with disease and of TT genotype with OR of 1.71 (CI 0.74-3.92, P=0.001) in co-dominant model. Allelic associations study indicated high frequency of G allele in healthy controls (P=0.01) compared to T allele in asthmatics (P=0.01) (Table IIB).

rs60389358: ARG1 genotype frequency distribution of SNP rs60389358 was not significant between asthma group and healthy controls in any of the models analyzed (Table IIA). However, significant allele association was observed where C allele was associated with asthmatics (P=0.04) compared to healthy controls in whom T allele was predominant (P=0.04) (Table IIB).

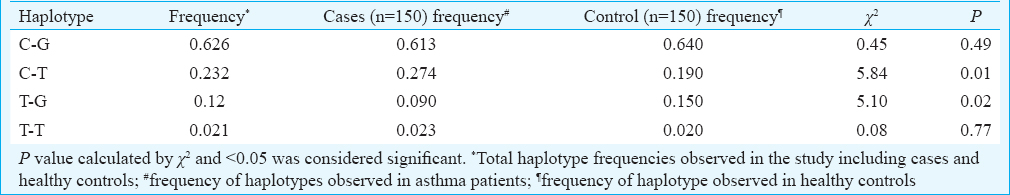

Haplotypes: Haplotype analysis indicated that C-T haplotype (rs60389358 and rs2781666) frequency was significantly higher in asthmatics (P=0.01) compared to healthy controls (Table III). In contrast, T-G (rs60389358 and rs2781666) haplotype frequency was high in healthy controls (P=0.02), indicating its negative association with asthma (Table III).

Linkage disequilibrium analysis between two ARG1 SNPs did not reveal any association (data not shown). Association between elevated arginase activity and SNPs (rs2781666 and rs60389358) was not observed (data not shown).

Discussion

Extensive studies on different experimental animal models for pathogenesis of asthma suggested that high arginase activity could be one of the reasons for AHR. Our observations on increase in arginase activity in asthma were similar to those in Oakland and Japanese population711. Increased arginase activity observed in non-atopics in the present study indicated a possible role in intrinsic asthma. The severity of the disease could be attributed to high serum arginase activity. This may perhaps lead to increased collagen, mucus production and peroxynitrite concentration resulting in constriction of the airways in asthma6. A study by Lara et al23 demonstrated that increased serum arginase activity and arginine bioavailability correlated strongly to lung function test (pulmonary function tests) in severe asthma group.

Inflammatory role of Th2 cytokines in AHR is well established. We observed elevated levels of IL-4 which was similar to the reports of others2425; in addition, a correlation was observed between elevated levels of IL-4 and severity of asthma. IL-13 levels were enhanced in our group of patients which was identical to the study by Deo et al24 from Mumbai. In contrast, IL-13 levels were reported lower in asthmatics compared to healthy individuals from Mysore by Davoodi et al26. It has been suggested that IL-4 and IL-13 inflammatory cytokines play a pivotal role in the induction of arginase via cAMP and JAK/STAT6 pathway in asthma11213. In vitro rat fibroblast when supplemented with IL-13 and IL-4 showed upregulated arginase activity which was inhibited by glucocorticoids27. In our study, a positive correlation between elevated serum IL-13 levels but not IL-4 with arginase activity was observed in asthma patients. Yang et al14 demonstrated in mice that IL-13-induced AHR was attenuated by inhibition of ARG1 activity and it alone may be sufficient to induce arginase in STAT6-dependent manner. As we observed positive correlation of the arginase activity with levels of IL-13, we hypothesize that this may lead to hyperresponsiveness in asthma in our patients.

With increase in serum arginase levels of asthmatics, further analysis of genetic variation in the promoter region of arginase gene (ARG1) assessed showed a significant association of ARG1 polymorphism at rs2781666 (G/T) position with susceptibility of asthma. Our results suggest that at rs2781666 homozygous GG genotype and allele G may offer protection and heterozygous GT genotype and T allele may confer susceptibility to asthma.

Although we did not observe any significant ARG1 genotype association of rs60389358 SNP with asthma, the alleles were associated where C allele towards susceptibility and T in protection from asthma. Duan et al18 studied arginase haplotypes using four different SNPs of arginase, of which rs60389358 SNP was found to be associated with altered bronchodilator response. Our haplotype analysis revealed that C-T haplotype (rs60389358 and rs2781666) might be susceptible to asthma whereas haplotype T-G (rs60389358 and rs2781666) might offer resistance to asthma. No correlation was observed between genotypes of rs2781666 and rs60389358 and elevated levels of arginase in the serum of asthma patients. The sample size was small between genotypes which might not be sufficient to correlate with arginase activity in the present study.

The incidence of asthma globally increased at faster rate and anticipated to reach 443 million by 202528. Asthma prevalence is soaring up in developing countries like India with huge economical burden29. Since asthma is a complex condition with the involvement of multiple mechanisms, there is a need for new therapeutic interventions. Animal models of asthma demonstrated that arginase is a key player in pathogenesis and its inhibition may lead to the reduction of AHR2101430. There are a few studies that showed the association of arginase with asthma in humans711.

Our findings demonstrated that elevated serum arginase activity and IL-13 levels and ARG1 rs2781666 G/T genotype might increase the risk of asthma. Therefore, the present study strengthens the argument that inhibition of arginase or IL-13 (which may have an indirect effect on arginase production) may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of asthma. A weak positive association was observed between IL-13 and arginase in a small portion of asthma patients; it could be due to low sample size which was a limitation of the study. Further, functional studies on the susceptible genotype/haplotype in ARG1 gene might provide an insight into the role and use of ARG1 gene as a genetic biomarker for asthma. It is well established that high IgE levels lead to manifestation of atopic asthma31. In this study that non-atopics did not have high IgE levels but had high arginase activity which correlated well with high IL-13 levels. The observations indicate the role of arginase in non-atopic asthma. Further studies are required on IL-13 receptor and its role on arginase induction to confirm this hypothesis.

Acknowledgment:

Authors thank the administration and management of Sreenidhi Institute of Science and Technology, Hyderabad, India for constant support and encouragement.

Financial support & sponsorship: Authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, for Senior Research Fellowship award (File no. 68/2/2013/ALL-BMS) to the first author (SD) which helped to carry out this work. This work was supported under R&D activity funds from Technical Education Quality Improvement Programme (TEQIP-II), World Bank Project (2012-2016).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Dissection of experimental asthma with DNA microarray analysis identifies arginase in asthma pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1863-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased arginase activity underlies allergen-induced deficiency of cNOS-derived nitric oxide and airway hyperresponsiveness. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:391-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased arginase activity contributes to airway remodelling in chronic allergic asthma. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:318-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arginase activity differs with allergen in the effector phase of ovalbumin- versus trimellitic anhydride-induced asthma. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:420-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transiently, paralleled upregulation of arginase and nitric oxide synthase and the effect of both enzymes on the pathology of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1419-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arginase: Marker, effector, or candidate gene for asthma? J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1815-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decreased arginine bioavailability and increased serum arginase activity in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:148-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gene expression profile of ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation in a murine model of asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:106-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Functionally important role for arginase 1 in the airway hyperresponsiveness of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L911-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- High serum arginase I levels in asthma: Its correlation with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J Asthma. 2011;48:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Th1/Th2-regulated expression of arginase isoforms in murine macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:3771-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- IL-4 and IL-13 upregulate arginase I expression by cAMP and JAK/STAT6 pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C248-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of arginase I activity by RNA interference attenuates IL-13-induced airways hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2006;177:5595-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic polymorphisms in arginase I and II and childhood asthma and atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:119-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Roles of arginase variants, atopy, and ozone in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:596-602. 602.e1-8

- [Google Scholar]

- ARG1 is a novel bronchodilator response gene: Screening and replication in four asthma cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:688-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulatory haplotypes in ARG1 are associated with altered bronchodilator response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:449-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Profile of pollen allergies in patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis and Urticaria in Hyderabad. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:221-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- SNPStats: A web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1928-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations of the arginine metabolome in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:673-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role played by Th2 type cytokines in IgE mediated allergy and asthma. Lung India. 2010;27:66-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased interleukin-4 and decreased interferon-γ levels in serum of children with asthma. Cytokine. 2011;55:335-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum levels of interleukin-13 and interferon-gamma from adult patients with asthma in Mysore. Cytokine. 2012;60:431-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glucocorticoid inhibition of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) induced up-regulation of arginase in rat airway fibroblasts. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;368:546-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Global Asthma Report 2018. 2018. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network; Available from: http://globalasthmareport.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Bronchial asthma - Issues for the developing world. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:380-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arginase inhibition protects against allergen-induced airway obstruction, hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:565-73.

- [Google Scholar]