Translate this page into:

Violence against doctors: A wake-up call

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

‘No physician, however conscientious or careful, can tell what day or hour he may not be the object of some undeserved attack, malicious accusation, black mail or suit for damages….’1

The above paragraph from a reputed Journal from the USA, written 135 years ago should be an eye-opener and also prophetic. Last few years, reports of violence against doctors, sometimes leading to grievous hurt or murder, are making headlines across the world23. Several such incidences have been reported from India also45; however, this menace has not been highlighted adequately. Whether the increase in reporting of violence truly represents a real increase in the prevalence of the condition or just represents increased awareness in the era of electronic mass media and improved telecommunication system needs further assessment.

Violence against doctors or other medical fraternity hardly made any news, or hardly there was discussion about this in India in medical journals about a decade back as they were probably infrequent though such violence in western countries was known67. In the majority of the cases (60-70%), such violence took the form of either verbal abuse or aggressive gesture. Very often, those who abused a medical person were patients themselves who were under the influence of alcohol and drug and were delirious or were in the psychiatry wards8. Increased risk of violence was also recorded when a general physician was on house calls, particularly at night9.

Over the last 40 years in western countries, the nature of such abuse has subtly changed. In most of the European countries and in Canada, the healthcare cost is borne by the government, and often, the first contact of the patient with medical service is with designated general practitioners who take house calls day and night; hence, there is no financial anxiety for medical treatment in these countries7. However, in the USA, although the standard of medical care may be high, yet this comes at a cost mostly through payment to insurance and companies or direct cost out of pocket. It has also been found that a large number of citizens of the USA could not afford to pay for the health insurance and fell out of care net210.

Recently in China one dentist was killed by his patient 20 yr after he treated his patients and the patient was aggrieved11. This indicates many of such violent incidences are not heat of the moment reaction but cold-blooded, calculated violence and murder. Several more acts of violence (called Yi Nao in Chinese) to doctors have been reported from China31213.

In western countries, high-risk areas have been identified as patient's house during house visits (particularly night) and waiting area in the clinic, paediatrics, physiology, emergency, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and major violence makers are patients or their close relatives281415. However, when we look at violence in Asian sub-continent including India, particularly against the doctors, a slightly different picture emerges. More often than not in India, patients by themselves are not violence makers, but their relatives are (Type II). Sometimes unknown apparently sympathetic individuals (Type I and Type IV), political leaders13 (not classified in western violence classification) and political parties take the law in their hand. One of the important dimensions of violence to the doctors in government and corporate hospitals is the feeling of wrong doing by the doctors for financial gain or for avoiding his/her duties. Anxiety, long waiting period before the patient could speak to a doctor and the feeling that doctor is not giving enough attention to his/her patients engender frustration giving rise to violence. Majority of the hospitals in India do not have good grievance addressal system in place. Legal procedure in India also takes inordinately long time.

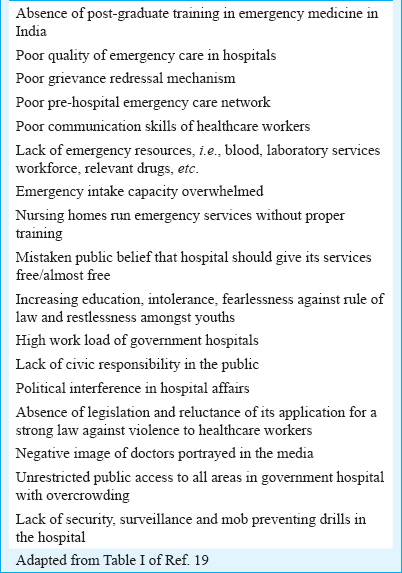

For government hospitals and primary health centres across the country, particularly in West Bengal and Maharashtra, violence by patients’ relatives, local goons, political leaders and even by police has been reported161718. Here, money is not the reason but anxiety, but long waiting period, non-availability of crucial investigations, inordinate delay in referral, unhygienic and extremely crowded condition in the emergency and other wards are some of the reasons given45. Electronic and print media also do not have real understanding of the challenges faced by the doctors. Factors associated with violence against doctors in India have been given below in tabular form19.

Now, what can be done to reduce the violence against doctors? If we look at the classification of patient violence2, in our country, most of the time, the violence refers to verbal abuse, vandalism and physical threat; most of the other forms of violence are yet to come to our society. However, the most important difference in violence as is seen in western countries is how quickly the verbal abuse becomes physical assault and vandalism and how rare it is that other patients and their relatives or third party make no efforts to stop it20. In this context, the observation by Mishra21 of the general deterioration of the morality ethics of intellectual class in India and rise of pseudo intellectuals as well as his suggestion that the violence could also be viewed with the prism class war22 need careful study. Several prescriptions for preventing violence to doctors have been provided in the literature starting from changing the curriculum of study, developing more communication skills, understanding by taking note of patients who could be violent, being cautious at violent venues, getting ready to run from the scene if situation demands, educating patients and their relatives, improving healthcare, etc8141923242526272829. While some of these prescriptions are implementable, some are obviously not.

What a doctor can or should do to avoid violence?

A doctor should understand some of those patient-related characteristics which may be associated with violence. While most of the items are associated with background psychological disturbance or substance abuse in the patient in the western examples of violence8, it does not have much implication in the current scenario of violence against doctors that has engulfed this country4519232425262728.

Heightened anxiety about the disease as well as finance needed for the disease seem to be an important component of initiation of violence and the doctor should train himself/herself for anxiety alleviation techniques. Studies have shown seniority of the doctor matters, i.e. a senior doctor faces less violence than junior doctors25232425, whether this is related to less exposure of senior doctors to explosive situation or his/her better handling the situation, his/her political influence or getting respect from patient's relatives because of his/her long years of experience has not been looked into.

Bereavement, young patient under serious condition, only earning member in the family and only child with serious disease evolve emotional outburst which may quickly end in violence. Doctor should have better training to tackle these situations. Long waiting hours and doctor's behaviour towards patients and relatives are important contributors to aggression279 and need to be addressed by the doctor as much as possible2619.

Doctors probably should try to optimize and reduce long waiting periods for the patients in the waiting rooms and try to improve patient contact as much as possible. Use of digital technology, mobile phones, may be useful to achieve this end. For example, it has repeatedly been seen that long queues in the hospital, lack of communication from the doctors and opaque billing systems are important predictors of violence in India. Both digital and mobile technology can substantially help in this area3031.

What the hospital should do?

Hospitals can do much to reduce the violence. In government hospitals, this can be done as a part of general reform for the hospital services in the form of: (i) Improvement of services in a global fashion; (ii) employment of adequate number of doctors and other steps to ease the rush of patients and long waiting hours; (iii) use of computer and internet technology; (iv) hospital security should be strengthened and it needs to be properly interlocked with nearby police station; (v) no arms/ammunition by patient or their relatives should be allowed inside the hospital; (vi) there should be transparency on rates of different investigations, rents and other expenses in the hospital; and (vii) there should be a proper complaint redressal system in the hospital.

What the patient family and society at large should do to prevent the violence?

There is immense responsibility of patients, their relatives and society at large to prevent this violence. Disputes between patients and hospitals or doctors are not to be sorted through violence, but in a civilized society, there are avenues of dispute redressal which should be used.

Modern medicine is neither cheap nor 100 per cent effective in curing the disease in all cases. There should not be under-expectation on the outcome of the treatment in a serious case. Some patients will make it, some patients will not. This should be clearly understood.

There should be an understanding that vandalism and violence in a hospital or clinic is a criminal offense and any civilized society should have low tolerance for such heinous acts. Hardly social leaders are seen to condemn such violence today, and surprisingly sometimes they try to justify the situation.

Responsibility of the media

It is the responsibility of both print and electronic media not to sensationalize the news. Medicine is not a black and white subject and so also its management. Diagnosis of a patient is essentially hypothetico-deductive process, and with new evidence through investigations and knowledge, the diagnosis of some of the cases continues to be refined. However, whatever the diagnosis be, the management of patient generally includes such uncertainties into account and treatment continues.

Responsibility of the government and political parties

In India, the cause of violence against doctors is multi-layered. Spending around 1 per cent of the GDP by the government in a population which increased five times since independence is not enough. Modern medicine is progressing by leaps and bounds, but most of the medical colleges and hospitals in the country could not keep place with the progress (Table). The government needs to put the effort to see how the overcrowding in the hospitals can be prevented. No nation can build hospitals for 1300 million patients, but it is possible to build hospital for 1300 million citizens who are largely healthy. To keep 1300 million people healthy in a country like India is a humongous task. Nutrition, immunization, health education, pollution control, personal hygiene, access to clean water, unadulterated milk, unadulterated food, facilities for exercise, playground, etc. are the basic requirements. The government should concentrate its activities on preventive medicine. The government should punish unlawful behaviour of anybody who harms the doctor and vandalizes the hospital.

Conclusion

Although violence against doctors and other health workers is not uncommon, the incidence in India seems to be increasing. Many remedies have been advised to tackle this situation, some of those are discussed here. As there are certain responsibilities of doctors and other healthcare workers, similarly, responsibilities also have to be borne by patients and their relatives, political parties, hospital authorities, law maintaining machinery, media and government to see that health care improves and violence against doctors is strongly dealt with. There is a need for a detailed longitudinal study across the country to understand the prevalence, nature and regional differences in violence perpetrated against doctors in this country. An ongoing study by Indian Medical Association (IMA) reports that 75 per cent of doctors in India have faced violence at some point of time in their life, and most of the time, it is verbal abuse. Emergency and ICU are the most violent venues and visiting hours is the most violent time31. There is no reason to wait now to stop this violence against doctors and take preventive measures.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuing violence against medical personnel in China: A flagrant violation of Chinese law. Biosci Trends. 2016;10:240-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Violence against doctors in the Indian subcontinent: A rising bane. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:749-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Workplace violence against resident doctors in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi. Natl Med J India. 2016;29:344-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: A cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:263-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Violence in general practice: A survey of general practitioners’ views. BMJ. 1991;302:329-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Repealing the ACA without a replacement – The risks to American health care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:297-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- News Report: Retired Dentist Dies after Being Stabbed by Ex-Patient. 2016. South China Post. Available from: https://www.scmp.com › News › China

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the safety measures by doctors on after-hours house call services. Australas Med J. 2015;8:239-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Over 75% of Doctors Have Faced Violence at Work, Study Finds – Times. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Over-75-of-doctors-have-faced-violence-at-work-study-finds/articleshow/47143806.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Cop ‘Beats Up’ Doctor at Sassoon Hospital. Pune. Available from: https://www.indianexpress.com/article/cities/pune/cop-beats-up-doctor-at-sassoon-hospital/

- [Google Scholar]

- Jr. Doctors Take to Streets to Protest RG Kar Attack after Patient's Death. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/jr-doctors-take-to-streets-to-protest-rg-kar-attack-after-patients-death/articleshow/57819134.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Mob Assaults Doctor, Smears him with Human Excreta Kolkata News. Available from: https://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/mob-assaults-doctor-smears-him-with-human-excreta/articleshow/60294926.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- The 2017 academic college of emergency experts and academy of family physicians of India position statement on preventing violence against health-care workers and vandalization of health-care facilities in India. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2017;7:79-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- It doesn’t “come with the job”: Violence against doctors at work must stop. BMJ. 2015;350:h2780.

- [Google Scholar]

- Our intellectuals have failed us – System of a down. Indian Heart J. 2017;69:133-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of workplace violence experienced by doctors and associated risk factors in a tertiary care hospital of South Delhi, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:LC06-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Violence against doctors on the increase in India. Natl Med J India. 2015;28:214-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidents of violence against doctors in India: Can these be prevented? Natl Med J India. 2017;30:97-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is changing curriculum sufficient to curb violence against doctors? Indian Heart J. 2016;68:231-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microblogging violent attacks on medical staff in China: A case study of the Longmen county people's hospital incident. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:363.

- [Google Scholar]