Translate this page into:

Microsatellite instability & survival in patients with stage II/III colorectal carcinoma

Reprint requests: Dr Srdjan Markovic, Dimitrija Tucovica 161, 11000, Belgrade, Serbia e-mail: srdjanmarkovic@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The two key aspects associated with the microsatellite instability (MSI) as genetic phenomenon in colorectal cancer (CRC) are better survival prognosis, and the varying response to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy. This study was undertaken to measure the survival of surgically treated patients with stages II and III CRC based on the MSI status, the postoperative 5-FU treatment as well as clinical and histological data.

Methods:

A total of 125 consecutive patients with stages II and III (American Joint Committee on Cancer, AJCC staging) primary CRCs, were followed prospectively for a median time of 31 months (January 2006 to December 2009). All patients were assessed, operated and clinically followed. Tumour samples were obtained for cytopathological verification and MSI grading.

Results:

Of the 125 patients, 21 (20%) had high MSI (MSI-H), and 101 patients (80%) had MSI-L or MSS (low frequency MSI or stable MSI). Patients with MSS CRC were more likely to have recurrent disease (P=0.03; OR=3.2; CI 95% 1-10.2) compared to those with MSI-H CRC. Multi- and univariate Cox regression analysis failed to show a difference between MSI-H and MSS groups with respect to disease-free, disease-specific and overall survival. However, the disease-free survival was significantly lower in patients with MSI-H CRC treated by adjuvant 5-FU therapy (P=0.03).

Interpretation & conclusions:

MSI-H CRCs had a lower recurrence rate, but the prognosis was worse following adjuvant 5-FU therapy.

Keywords

Chemotherapy

colon cancer

5-fluorouracil

microsatellite instability

prognosis

Colorectal cancer (CRC) shows a significant heterogeneity in prognosis and response to therapy, even within the same pathological stage. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is an established factor in the pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma, affecting the majority of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) cases, and approximately 15 per cent of sporadic CRC1. MSI occurs when the DNA repair system fails to fix replication errors that occur within the repeating microsatellites sequences23. The role of MSI as a prognostic factor in cure and survival is conflicting. A number of studies showed MSI to be a beneficial prognostic factor45678, while other studies showed no relation between the presence of MSI and survival rates910. The CRC prognostic maze gets more complex in patients scheduled for adjuvant 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) therapy, as the success of 5-FU is inversely related to MSI severity1112. Therefore, the mechanism, which leads these tumours to a more favourable prognosis, is unclear.

Despite advances in CRC pathophysiology, staging remains the most reliable predictor of survival and therapeutical management in CRC patients13. Moreover, adjuvant chemotherapy for surgically treated patients with stage II CRC is controversial14. Therefore, in 30-40 per cent of AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer)15 stages II and III patients who eventually relapse, adjuvant 5-FU chemotherapy is recommended. The aim of this study was to measure the survival of surgically treated patients with stages II and III CRC (according to AJCC classification)15 based on the MSI status, the postoperative 5-FU treatment as well as clinical and histological data.

Material & Methods

Tumour tissue samples were obtained from 125 consecutive adult patients with CRC at the Digestive Surgery Clinic, Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade, from January 2006 to December 2009 (mean age 62.5±11 yr, 77 men and 48 women). Patients pretreated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy, those with inflammatory bowel disease, HNPCC (Amsterdam criteria)16 or a known history of familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded from this study. Sixty three patients received adjuvant 5-FU chemotherapy independently of the MSI status. All patients were followed until October 1, 2011, or end of their life. Clinical progress was followed up either by scheduled appointments or telephone interviews with the patients or their families. The primary outcomes in this study were: overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and disease specific survival (DSS). Overall survival was defined as the time from the entry into the study to death. Disease-specific survival was defined as the time from the entry to death due to CRC. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from the entry to the first confirmed relapse (any recurrence) or death due to CRC17. This prospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Center of Serbia, Belgrade, and all patients gave informed consent prior to study participation.

Clinical and pathological analysis: Tissue samples fixed in 10 per cent formalin, were processed, embedded in paraffin blocks and cut at 2-3μm thickness. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as well as periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were used for routine and mucin staining, respectively. In addition, PAS/Alcian blue was used to stain the neutral and acidic mucin. Patients with stages II and III CRC (AJCC classification) were examined, following a histopathological verification by a pathologist who was blinded to the CRC MSI status. Localization (right, left colon and/or rectum), tumour cell type, tumour differentiation, mucin production, lymphocyte infiltration tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were determined in all tumours.

All tumours were adenocarcinomas. TILs were graded as absent (0) or present (1). Tumours were classified as positive TILs if at least five lymphocytes were observed per 10 high-power fields. Mucin content was scored from one to three (score one, two and three for tumour mucin volume 0-33, 33-66 and 66-100%, respectively)18. Tumour differentiation was classified as poor (1), moderate (2) or well (3)19. Serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were assessed preoperatively and quantified using an electrochemiluminescence assay (ECLIA) on Cobas e 411 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's testing protocol. The CEA upper reference interval limits were 5.5 and 3.8 ng/ml for smokers and non-smokers, respectively.

Analysis of microsatellite instability: Tissue samples from tumours and control vehicles (normal colorectal mucosa) were immediately frozen at - 80C. Genomic DNA was extracted using standard methods: five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats and pentaplex PCR for evaluating the microsatellite tumour status, as described previously2021. Five mononucleotide markers, BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22 and NR-24, were co-amplified in a single pentaplex PCR mix containing QIAGEN Multiplex PCR Kit, Germany, five fluorescent primer sets in final concentration, 0.25 μmol/l of each primer and 100 ng of DNA, by the previously described conditions2223. The sizes of the PCR products and corresponding fluorescent labelled Gene Scan™ 500LIZ@ Size Standard, USA were analysed in ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) using Gene Mapper Software version 3.7, USA. This allowed simultaneous analysis of normal-sized alleles, with the smaller-sized alleles containing deletions typically seen in tumours with high MSI (MSI-H). tumours were classified as MSI-H if two or more of the five markers showed MSI, and MSI-L (low MSI), if only one marker showed MSI. Microsatellite stable (MSS) tumours were characterized by the absence of MSI in all five markers. MSI positive markers were re-examined twice to confirm the result.

Statistical analysis: Clinical and pathological factors were analysed using chi square test or unpaired Student's t test. Recurrence-free probabilities, cancer-specific and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method17, and the log-rank test was used for the statistical differences. Time of surgery was set as time zero. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the association between MSI status or clinical and pathological characteristics of tumour and any recurrence, locally or distant, as well as the cancer-specific and overall mortality.

Results

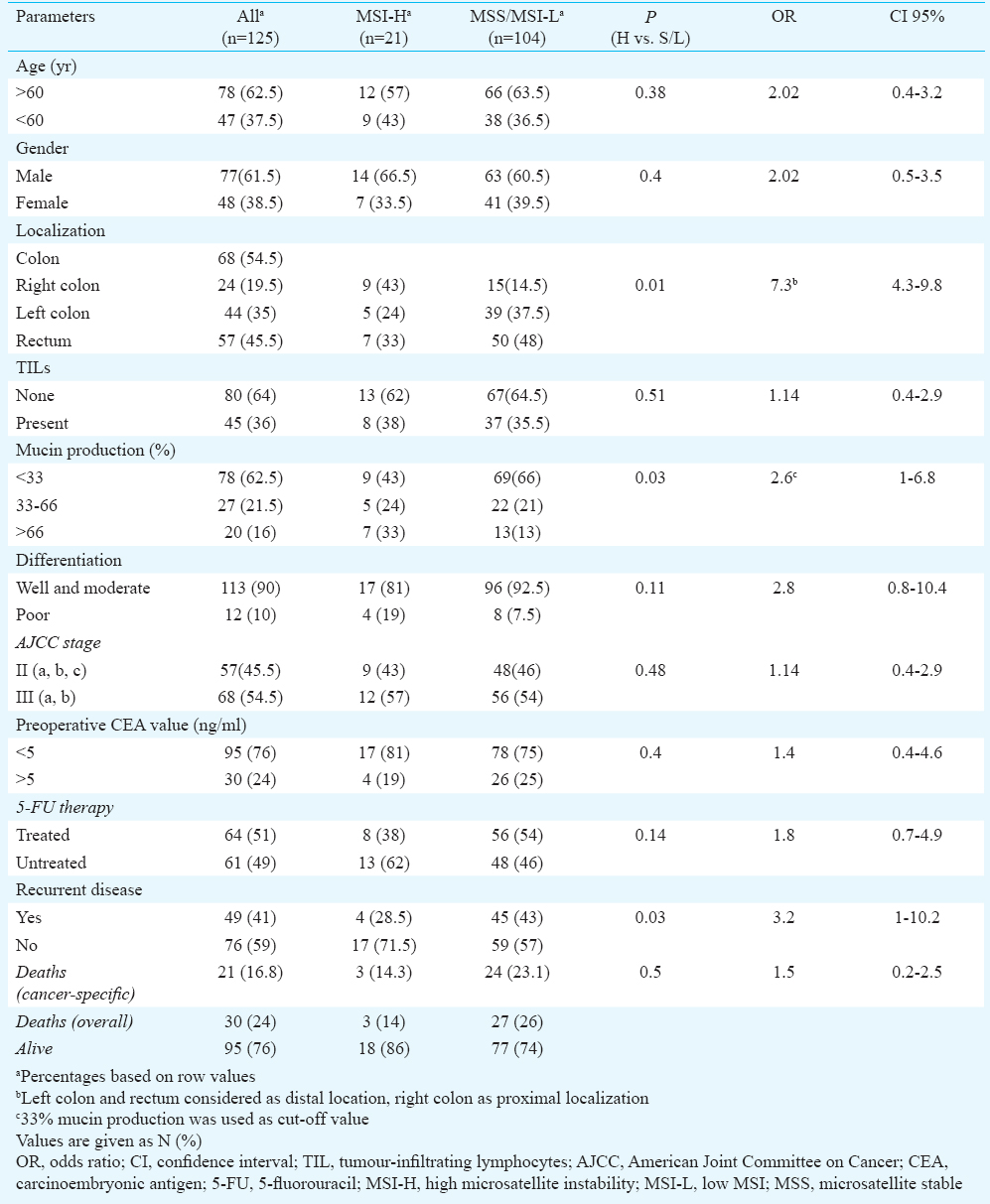

Patient demographics, clinical and pathological profiles stratified by MSI status are presented in Table I. In relation to the MSI status, tumours were classified in two groups: MSS/MSI-L and MSI-H group. The median (range) follow up period after surgery was 31 (1 - 66) months. The mean ages of patients in MSS/MSI-L and MSI-H groups were 63±11.2 and 62±9.3 yr, respectively. Older patients had a lower OS (hazard ratio, HR, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, CI; P=0.017), but DSS was similar to younger patients. The majority of patients in MSI-H group were males (73.5%), but there was no significant relationship between MSI status and gender. Male patients had lower OS (HR, 2.31; 95% CI; P=0.044).

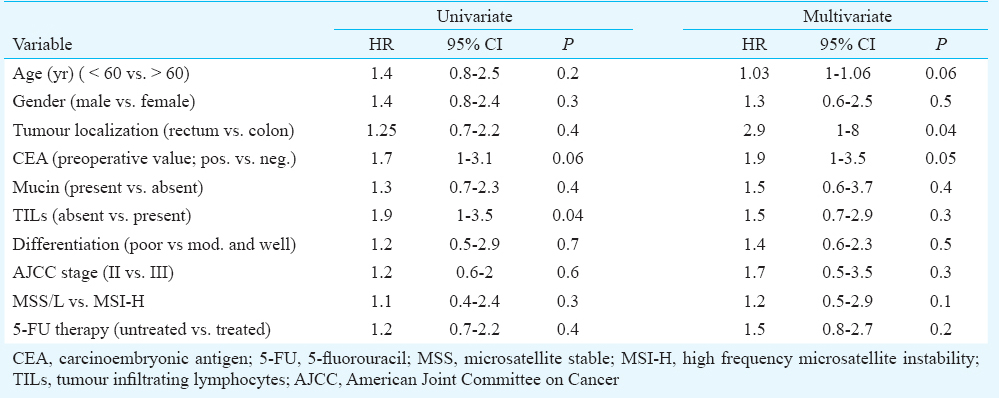

Gender and age were not independent factors for cancer-specific survival and disease recurrence (Tables II and III). Twenty four lesions were located in the proximal, right colon (19.5%). The prevalence of proximal lesions in the MSI-H group (43%) was higher than in the MSS/MSI-L group (14.5%, P=0.01; Table I). TILs were associated with disease recurrence as well as preoperative CEA value (P<0.05), and tumour localization were found to be independent factors for disease recurrence, when multivariate Cox regression analysis was used (Table II).

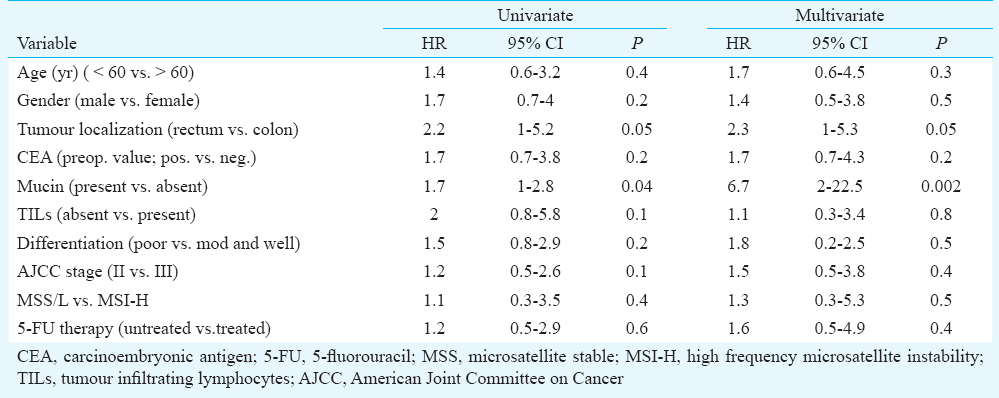

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the prognostic factors revealed that rectal cancers and presence of mucin in tumour tissue were significantly associated with worse DSS (Table III). No other significant associations between other examined clinicopathological factors (gender, age, tumour differentiation, TILs, AJCC stages, preoperative CEA value) and DSS were observed (Table III).

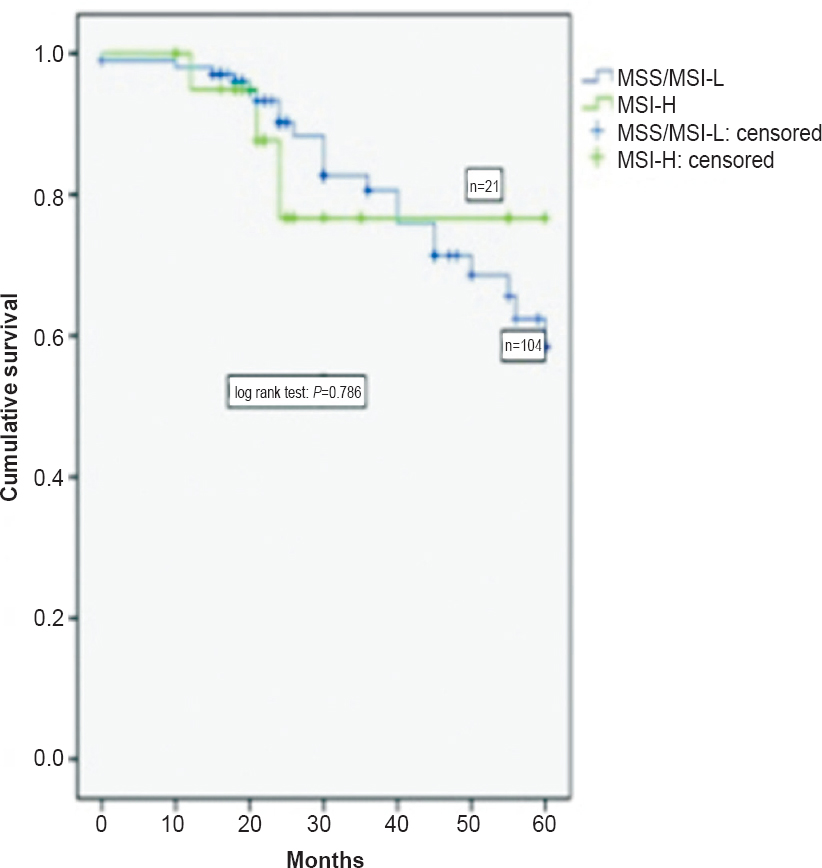

Twenty one (20%) of 125 patients with colorectal cancers had MSI-H, and 104 (80%) patients were MSS/MSI-L. In the group with MSI-H tumours, three deaths and recurrence of disease in four patients were reported. Tumours with MSS/MSI-L status (45/104) had a greater tendency to recurrence compared to MSI-H tumours (4/21; OR=3.2; CI 95% 1-10.2; P<0.05) (Table I). Tumour MSI status was not a significant prognostic factor for disease recurrence and cancer-specific survival, according to the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. There was no difference in disease-specific survival between MSI-H and MSI-L/MSS tumours (log-rank test: P=0.786, Fig. 1).

- Disease-specific survival of patients according to MSI phenotype.

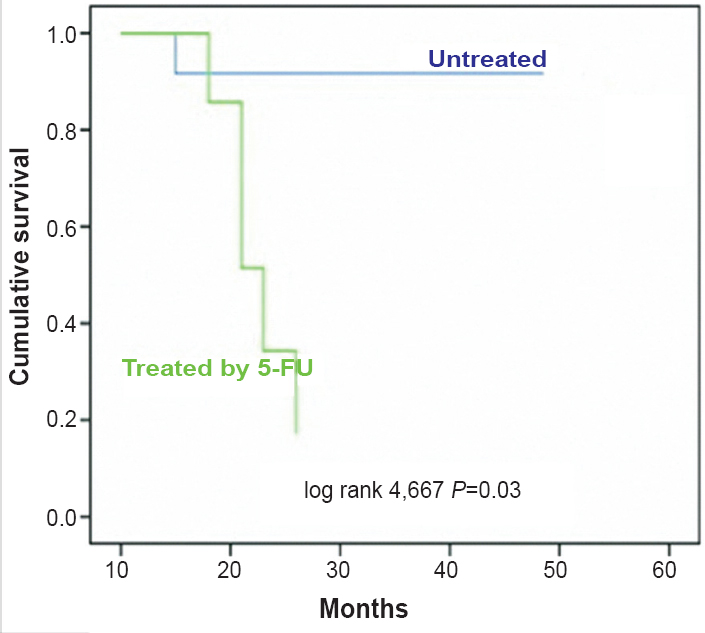

Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU was administered to 63 patients (16 patients with stage II and 47 with stage III disease). No difference was found in the overall and disease-specific survival compared to the MSI status of tumours stratified by treatment with 5-FU chemotherapy. DFS was significantly lower in patients with MSI-H CRCs who were treated by adjuvant therapy (log rank test, P=0.03, Fig. 2). Using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis the treatment with 5-FU was not an independent factor associated with disease recurrence and DSS (Tables II and III).

- Disease-free survival of patients with high microstatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal cancer according to 5-flurouracil (5-FU) treatment.

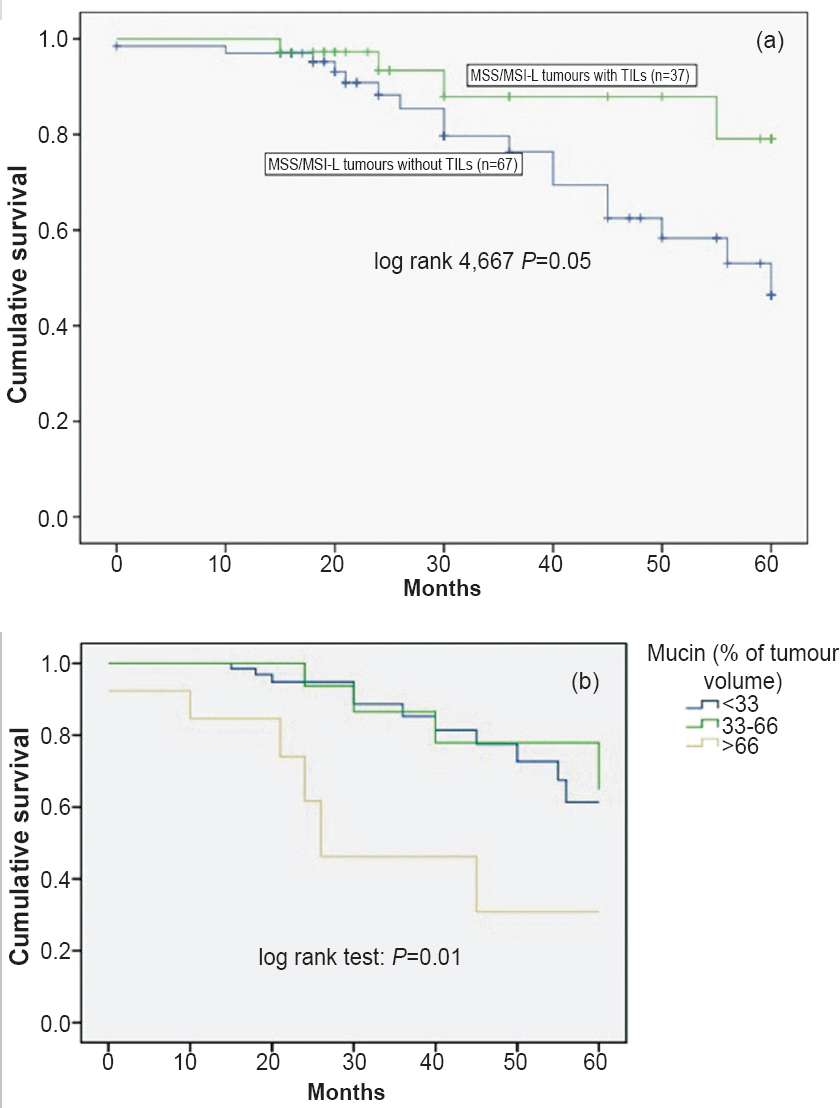

Patients with MSS/L tumours without TILs had a lower DSS (log rank test; P=0.05) compared to those with TIL. The same group of patients (MSS/L) with presence of mucin (more than 66% of tumour volume) had a lower cancer-specific survival (log rank test; P<0.05, Fig. 3a and 3b), compared to those with mucin ≤ 66 per cent of tumour volume.

- Pathological features and disease-specific survival of patients with stable microsatellite/low MSI (MSS/MSI-L) according to: (a) tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs); (b) mucin content.

Discussion

More than 150,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with stage II and III CRC each year2425. The decision to treat patients with chemotherapy following surgery is based on the likelihood of disease recurrence. Determination of the MSI status is controversial in terms of survival and adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II CRC26. Patients with stage I CRC have better prognosis, and do not require adjuvant chemotherapy, unlike patients with stage IV CRC. Many studies suggested a better overall and disease-free survival of patients with MSI-H tumours567827, and several studies failed to confirm these finding910142829. Our study demonstrated that patients with MSI-H tumours had a significantly lower rate of disease recurrence, however, the survival for patients with MSI-H CRC was not improved overall. The discrepancy in results between this and other studies may be due to the heterogeneity, particularly in patient selection criteria.

Ogino et al30 suggested that lymphocytic reaction to CRC was associated with longer survival independent of other clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics. In our patients, TILs, preoperative CEA value and tumour localization were independent prognostic factors for cancer-free survival. For example, high preoperative CEA levels were associated with an increased risk for recurrence and poor survival31, a finding similar to our study. The presence of mucin in CRC, has uncertain effects on disease survival222332. In our study microsatellite stable tumours with mucinous differentiation had worse cancer-specific survival. Further, this pathological feature was an independent factor for worse DSS along with the tumour localization. In contrast, presence of mucin did not predict the disease outcome in patients with MSI-H CRC.

Another aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between the MSI status and the response to chemotherapy. It has been found that the patients with MSS/MSI-L CRC may benefit from 5-FU based chemotherapy92933. Other studies have shown that patients with MSI-H CRC have the same response to 5-FU therapy, as patients with MSS/MSI-L CRC91432. Here we demonstrated that patients with MSI-H CRC treated with 5-FU chemotherapy had frequent relapses. This suggests that 5-FU therapy probably has no effect in patients with MSIH CRC.

In conclusion, our study contributed to the current understanding of the MSI status of tumour as a prognostic survival factor. First, our results supported the view that MSI-H CRC might be resistant to 5-FU based chemotherapy. Second, patients with MSI-H CRC had lower recurrence rate, but no significant disease specific and overall survival was observed. Third, patients with MSI-H CRCs treated with adjuvant 5-FU therapy had lower disease-free survival. Fourth, in terms of pathological features and MSI phenotype, patients with MSS CRC with excessive mucin production with or without TILs had worse disease-specific survival. Finally, low preoperative CEA levels associated with positive TILs in tumour tissue favoured longer disease-free survival of stage II/III patients with CRC.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by a grant of The Ministry of Science, Republic of Serbia: Grant No ON145079; Belgrade, Serbia.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1481-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite instability affecting the T17 repeats in intron 8 of HSP110, as well as five mononucleotide repeats in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Biomark Med. 2013;7:613-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival in stage II/III colorectal cancer is independently predicted by chromosomal and microsatellite instability, but not by specific driver mutations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1785-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:609-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite instability and adjuvant fluorouracil chemotherapy: a mismatch? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3207-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite and chromosomal stable colorectal cancers demonstrate poor immunogenicity and early disease recurrence. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:601-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced likelihood of metastases in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer. 2007;13:3831-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of 5-fluorouracil and survival in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:394-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of TP53 mutation is more relevant than microsatellite instability status for the prediction of disease-free survival in adjuvant-treated stage III colon cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5635-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does microsatellite instability predict the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1890-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite instability as a marker in predicting metachronous multiple colorectal carcinomas after surgery: a cohort-like study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:329-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsatellite instability did not predict individual survival of unselected patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:145-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of stage and clinical/prognostic factors for colon and rectal cancer from SEER registries: AJCC and collaborative stage data collection system. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 23):3793-806.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival analysis in clinical trials: Basics and must know areas. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:145-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Classificaiton of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- New criteria for histologic grading of colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:193-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of tumor microsatellite instability using five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats and pentaplex PCR. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1804-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats for high-level microsatellite instability analysis. Dis Markers. 2004;20:251-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and survival of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colorectum: a population-based study from an Asian country. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:78-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- A 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1161-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- MACC1, a newly identified key regulator of HGF-MET signaling, predicts colon cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2009;15:59-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel expression patterns of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway components in colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:767-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and survival of carriers of mutations in DNA mismatch-repair genes in colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2751-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability and Ki-ras mutation type in stage II colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2003;64:259-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mismatch repair status in the prediction of benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006;55:848-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, independent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6412-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum carcinoembryonic antigen monitoring after curative resection for colorectal cancer: clinical significance of the preoperative level. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3087-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse prognostic effect of methylation in colorectal cancer is reversed by microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3729-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:247-57.

- [Google Scholar]