Translate this page into:

Health literacy on tuberculosis amongst vulnerable segment of population: special reference to Saharia tribe in central India

Reprint requests: Dr M. Muniyandi, National Institute for Research in Tribal Health (ICMR) Nagpur Road P.O., Garha, Jabalpur 482 003, Madhya Pradesh, India e-mail: mmuniyandi@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Health literacy on tuberculosis (TB) is an understanding about TB to perform activities with regard to prevention, diagnosis and treatment. We undertook a study to assess the health literacy on TB among one of the vulnerable tribal groups (Saharia) in central India.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 2721 individuals aged >15 yr from two districts of Madhya Pradesh State of India were interviewed at their residence during December 2012-July 2013. By using a short-form questionnaire, health literacy on cause, symptoms, mode of transmission, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of TB was assessed.

Results:

Of the 2721 (Gwalior 1381; Shivpuri 1340) individuals interviewed; 76 per cent were aged <45 yr. Living condition was very poor (62% living in huts/katcha houses, 84 per cent with single room, 89 per cent no separate kitchen, 97 per cent used wood/crop as a fuel). Overall literacy rate was 19 per cent, and 22 per cent had >7 members in a house. Of the 2721 respondents participated, 52 per cent had never heard of TB; among them 8 per cent mentioned cough as a symptom, 64 per cent mentioned coughing up blood, and 91 per cent knew that TB diagnosis, and treatment facilities were available in both government and private hospitals. Health literacy score among participants who had heard of TB was <40 per cent among 36 per cent of respondents, 41-60 per cent among 54 per cent and >60 per cent among 8 per cent of respondents.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The finding that nearly half of the respondents had not heard of TB indicated an important gap in education regarding TB in this vulnerable population. There is an urgent need to implement targeted interventions to educate this group for better TB control.

Keywords

Health literacy

Saharia tribals

tuberculosis

vulnerable tribal groups

Poor health literacy is common among people who have low educational attainment, immigrants, elders and racial and ethnic minorities1. Research from developed countries demonstrated that the level of health literacy expected was the constellation of skills, the ability to perform basic reading and tasks required to function in the health care environment such as reading labels on drug bottles, interpreting the test results, dosing of drugs, educational brochures or informed consent documents. This was studied in disease specific literacy level like type 2 diabetes, hypertension2, asthma3, and AIDS4. However, in developing countries similar studies are not available.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major global health problem and India remains as one of the most TB affected countries in the world. As per census of India 2011, the scheduled tribe (vulnerable population) population in India comprises nearly one tenth of the country's population5. Any development programme initiated by the Government of India will take time to reach this segment with limited access to health care services due to isolation, low social status and weaker economic position. Studies undertaken by the National Institute for Research in Tribal Health (NIRTH), Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, estimated the magnitude of TB among particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs) and reported a high burden of TB among Saharia tribes (1518/100000) which is one of the PVTGs in India67.

We undertook this study to assess the disease specific literacy on TB among this tribal population in terms of their awareness on symptoms suggestive of TB, preventive measures, mode of transmission, availability of diagnostic, and treatment facilities.

Material & Methods

Study area: The areas of habitation of Saharia population in Madhya Pradesh are Gwalior, Datia, Morena, Sheopur, Bhind, Shivpuri, Ashoknagar and Guna. This study was carried out in two selected districts namely, Gwalior and Shivpuri, considering the operational feasibility, rapport with community and support by district authorities. Community survey done among Saharias in these districts by NIRTH showed that most of them were labourers with annual family income of < ₹10000. Majority were illiterate and they resided in Kachcha houses/huts with no separate kitchen in houses. In these districts as per the RNTCP (Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme) quarterly reports, 2014, the total case detection rate (CDR) was (144/100,000) less than the expected 216/100,000 population and new smear positives CDR was 61 as against the expected 80/100,000 population8.

Study population: This study was carried out between December 2012 and July 2013, and the data from each district were collected by two independent teams during the same period. Both male and female individuals aged >15 yr were included in this study. Considering the prevalence of risk to develop TB (50%), level of confidence (95%), precision (5%) and design effect (3), the required sample size to assess the health literacy was estimated to be 1200 from each district. All the villages were arranged in descending order of the tribal population and those villages with more than 80 per cent tribal population were selected. A village was considered as a sampling unit and required number of villages was selected using probability proportional to the size of each block in the district in order to cover the estimated sample size.

Data collection: Semi-structured, pre-coded, pre-tested questionnaire was used for data collection. The interviews were conducted at home in their local language (Hindi) by trained field investigators. The interview included household identification, demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents. In addition, data on health literacy on TB such as cause of TB, signs and symptoms of TB, mode of transmission, diagnosis and treatment and preventive measures were also collected from the individual respondents at their residence available at the time of survey. The interview teams were supervised by trained supervisors during data collection. All the filled forms were sent to NIRTH, Jabalpur, to check for correctness and completeness, any incomplete forms were sent back to field for corrections within 15 days.

Overall health literacy about TB was assessed based on the following items: (i) symptoms of TB (persistent cough for 2 or more weeks, sputum with blood, chest pain, weight loss, loss of appetite, fever, and night sweat), (ii) recognize TB as a transmissible disease, (iii) enumerate correct mode of transmission of TB (cough/sputum from infected persons), (iv) TB is treatable, (v) TB diagnosis tests, (vi) effective allopathy treatment for TB, and (vii) correct preventive methods for TB (covering nose/mouth while sneezing/coughing, not spitting everywhere, BCG vaccination). Total 20 questions and score of one (1) was given to correct responses and zero (0) for incorrect/do not know responses. Only respondents who had ever heard of TB were asked these questions. Responses were added together for each respondent to generate a literacy score (converted to percentage) ranging from minimum of zero to maximum of 100. The composite score was categorized into three grades low, medium and high using cut-off value of <40, 41-60 and >60. The similar methodology was used by World Bank to compile the Knowledge Economy Index9 and by Tobin et al10 to assess the knowledge and attitude to pulmonary tuberculosis in rural Edo state, Nigeria.

Data management and analysis: Data entry was done by using the Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro) software package version 5.0 (cspro.software.informer.com/s.o, USA). Data entry format was developed with logical expressions and conditional statements used to minimize the errors in data entry. Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS/PC version 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) package. In univariate analysis, Chi square test was used to compare the level of health literacy on TB with their demographic, socio-economic characteristics and tested for statistical significance. Multiple regression analysis was performed to find out the factors independently associated with the level of health literacy.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of NIRTH, Jabalpur, and respondents were interviewed after obtaining voluntary, written informed consent.

Results

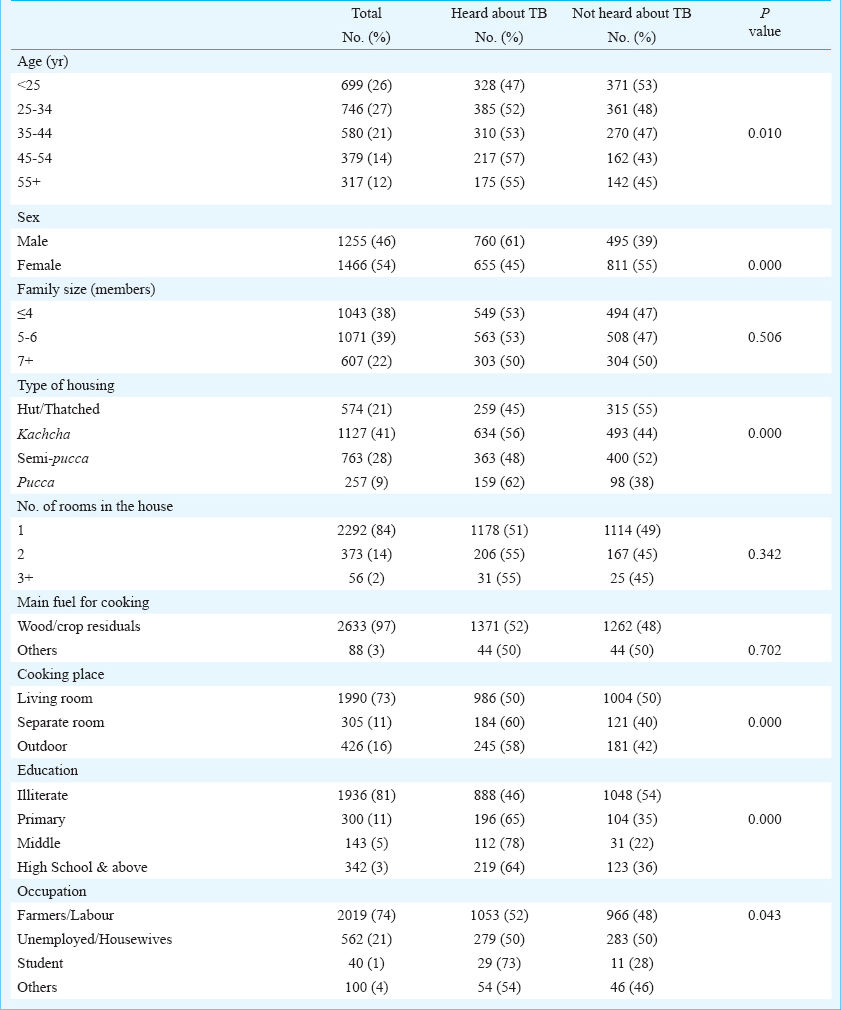

Of the 2721 persons enrolled in this study, 1381 (51%) were from Gwalior district and 1340 (49%) from Shivpuri district. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of study subjects are shown in Table I. Mean age of respondents was 39 yr and majority (74%) belonged to the age group of less than 45 yr. Regarding their housing conditions 21 per cent lived in huts, 41 per cent kachcha houses, 84 per cent in a house with single room, 89 per cent did not have separate kitchen (cooking either in living room or outside the house) and 97 per cent used wood or crop residuals as a fuel, overall literacy rate was 19 per cent; (11% completed primary and only 3 per cent completed High School and above). Family size indicated that 22 per cent of the study participants lived with more than seven members in a house.

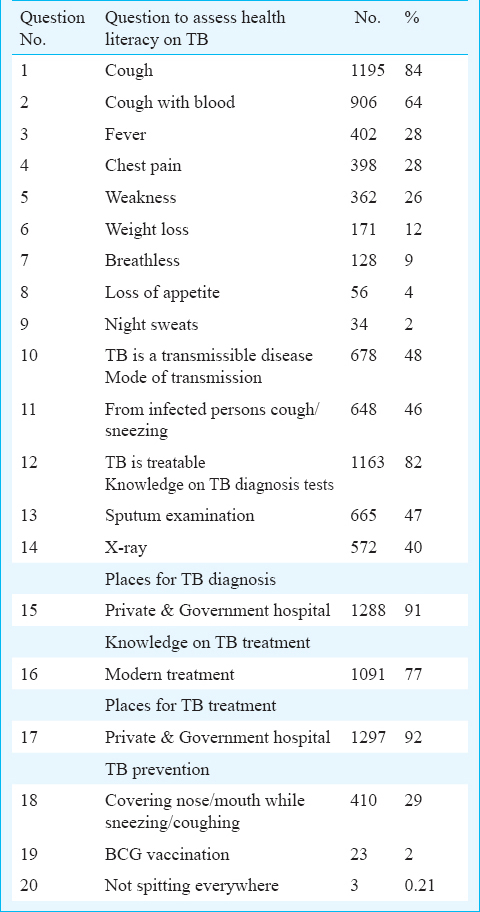

Health literacy on TB: Of the 2721 respondents participated, nearly half (n=1306, 48%) had not heard about TB. It was observed that majority were females (55%); illiterates (54%) and unemployed/housewives (50%) or farmers/labour (48%) (Table I). Respondents having heard of TB were asked to response 20 questions on TB. Table II indicates health literacy on TB in each item as reported by the respondents.

-

(i)

Symptoms of TB - Considering the total population, 44 per cent of the respondents mentioned that cough for more than two weeks as a symptoms of TB. Other symptoms mentioned by the respondents included cough with blood (33%), fever and chest pain (15%), weakness (13%) and only a few reported weight loss, breathlessness, loss of appetite and night sweats.

-

(ii)

TB transmission - Forty eight of the respondents stated TB as transmissible disease and 46 per cent Sated coughing/sneezing from infected person as a mode of transmission.

-

(iii)

TB diagnosis - About literacy on TB diagnosis 47 per cent answered that TB was diagnosed by sputum examination and 40 per cent by X-ray.

-

(iv)

TB treatment - Overall, 82 per cent of the respondents knew TB as a treatable disease. Further, majority (92%) reported that diagnosis and treatment facilities were available in both government and private hospitals.

-

(v)

TB prevention - Respondents were asked about the prevention of TB infection by three questions; 29 per cent were aware that TB infection could be prevented by covering nose/mouth while sneezing or coughing. Only two per cent knew about BCG vaccination and less than one per cent reported that ‘not spitting everywhere’ could also prevent TB.

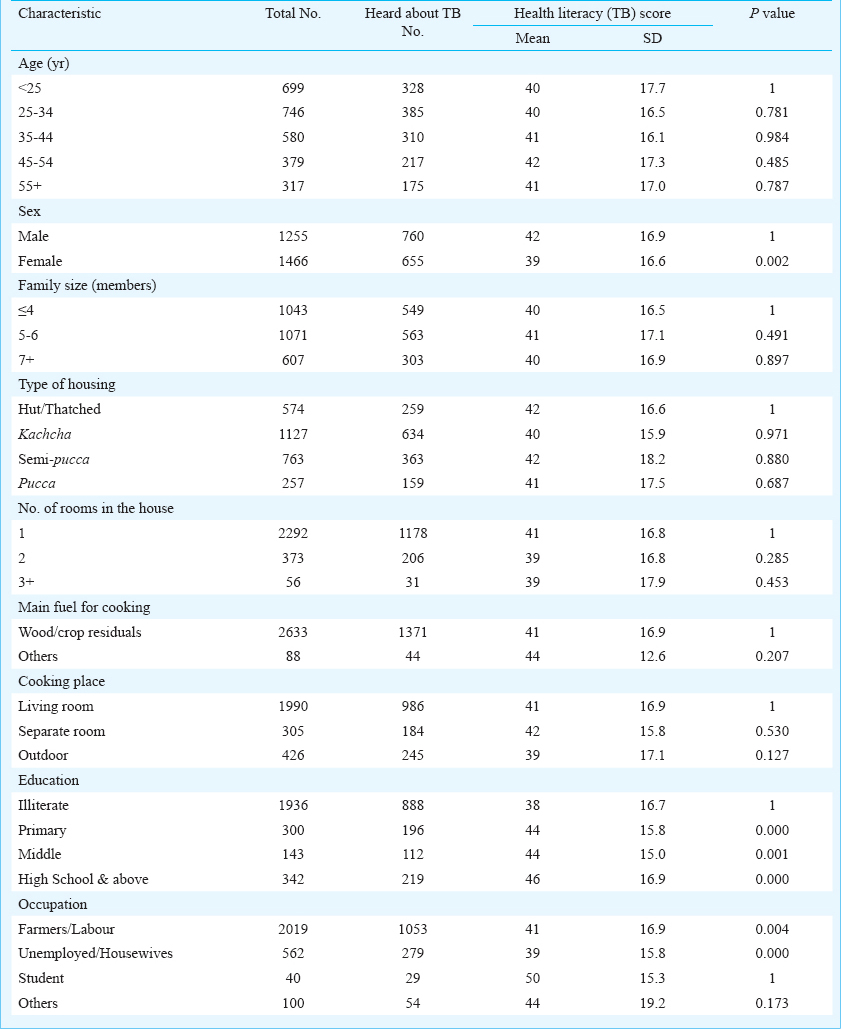

Overall score for ‘Health Literacy on TB’: Twenty questions on TB were used to assess the level of literacy on TB and 52 per cent participants who had ever heard about TB were interviewed to answer these questions. Of the 1415 respondents, 36 per cent scored less than 40 per cent, 54 per cent scored between 41-60 per cent and only 8 per cent scored more than 60 per cent. Health literacy scores according to respondent's demographic and socio-economic characteristics are given in Table III. The average score was significantly higher among males compared to females (42 vs 39; P=0.002), among literates (44 for primary & middle schooling, 46 for high school and above) as compared to illiterates (38; P<0.001). Students had significantly higher score (50) as compared to farmer/labourers (41) and unemployed/housewives (39). Multiple regression analysis was performed to find out the factors independently associated with health literacy on TB and, general education was the only factor independently associated with health literacy on TB.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to assess TB awareness with respect to disease symptoms, transmission, diagnosis, treatment and prevention among the tribal group. From the public health perspective health literacy may represent an important variable explaining the prevalence of poor health outcomes. In our sample, 52 per cent of respondents had heard about TB. This is low as compared to the national average of 88 per cent11. But among those who had heard of TB, the most significant finding that emerged from this study was 84 per cent knew cough as a TB symptom.

In this study, 48 per cent subjects had not heard of TB. This deficiency in health literacy on TB may hamper their treatment seeking behaviour and contribute to delay in diagnosis and treatment adherence leading to the high TB burden reported constantly in this segment of population67. Another significant finding was that among those who had heard about TB only a few respondents knew all the symptoms of TB and only one third mentioned any one preventive measure. In an earlier study the main reasons for not taking action were lack of awareness on TB (40%) and poor socio-economic condition (36%)12. Many of the lower socio-economic groups are not aware the risks associated with long standing cough. Saharia is not exceptional; they live in remote areas, not well connected through road/bridge network and lack of exposure to modern life has left Saharias economically weak tribe13.

Our findings corroborated with a study on TB done among sandstone quarry workers (83% were Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes) which reported low literacy on TB14. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act15 has enlightened health literacy as the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. Research indicates that nearly nine out of 10 adults have difficulty using the everyday health information that is routinely available in our healthcare facilities, retail outlets, media and communities16. Without proper information and an understanding of importance of information, people are more likely to skip necessary medical tests, end up developing the disease17. Care seeking behaviour1819 and delay in diagnosis of TB have been studied extensively in India and in other countries among general population2021 and in TB patients18. It was found that lack of education on TB symptom was one of the reasons for delay in diagnosis of TB222324. A study conducted in 2003 by Indian Institute of Health Management on accessibility and utilization of RNTCP services by Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe population in Madhya Pradesh reported that 18.9 per cent were unaware of the place to seek treatment25. In order to reach out to the particularly vulnerable group, an evidence-based and focused communication strategy has to be adopted to improve standards of care among these groups and to form scientific evidence based communication and social mobilization strategy2627.

The Government of India with Danish assistance to the National Tuberculosis Programme (DANTB) has done an informtion, education, communication (IEC) project in Odisha to develop innovative approaches and strategies as well as making use of successful experiences with health communication from other health programmes28. The innovations include patient provider interaction meetings; interactive stalls at weekly markets; a wide range of folk media; involvement of panchayat raj institutions, self-help groups and community-based organisations; as well as locally-designed IEC materials. Odisha became an IEC laboratory with involvement of villagers, DOT providers, former patients, health staff at all levels and non-government (NGOs) and voluntary organisations as laboratory technicians. This Odisha model of communication involved seven strategic elements: Universal right to know, Cultural sensitivity, Gender sensitivity, Community participation, Multi-level partnership, Appropriate media mix, Research, Monitoring and evaluation. These approaches can be utilized to increase health literacy in tribal areas.

There were some limitations of this study. A detailed questionnaire was used to collect information from tribal population. There might be a problem in the comprehension of the questions since most of the respondents were illiterate. Also health literacy from non-tribal population in the area was not compared. The questionnaire did not include data on ‘prior exposure to this disease either in self or in the family’. This valuble information was not collected.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate the need to develop working strategies to provide ‘Universal Access’ to TB care, especially among the tribal and socially vulnerable populations. Based on recommendations, working strategies could be framed for improving health literacy on TB among PVTG such as Saharia and incorporated in the ACSM (Advocacy, Communication and Social Mobilization) tribal plan for TB control in the country.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Neeru Singh, Director, NIRTH, Jabalpur, for her encouragement and support throughout the study. The authors acknowledge the District Tuberculosis Officer, the WHO/RNTCP consultant, District Tribal Welfare authorities, Block Medical Officers, and peripheral field staff in the district for the cooperation and assistance. Authors thank Ms Preeti Tiwari, Ms Swati Chouhan, Mrs Priyashri Tiwari Pandey and Ms Sneha Patel for data entry and cleaning; and Drs Rajeswari Ramachandran, T. Santha Devi, Former Deputy Directors Senior Grade, National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis (ICMR), Chennai, for their expert comments and assistance. The study was financially supported by the Adim Jati Kalyan Vibhag, through the District Administration, Gwalior.

References

- Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs. Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA. 1999;281:552-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114:1008-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health literacy and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:325-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affair, Government of India. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of pulmonary tuberculosis in a primitive tribe of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Tuberc. 1996;43:85-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary tuberculosis: a public health problem amongst Saharia, a primitive tribe of Madhya Pradesh, central India. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e713-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central TB Division. In: RNTCP Annual Report 2014. New Delhi: Central TB Division, Directorate of General Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Measuring knowledge in the world's economies: Knowledge assessment methodology and knowledge economy index. The World Bank Institute, Knowledge for Development (K4D) Program, Washington. 2012. Available from: www.worldbank.org/wbi/knowledgefordevelopment

- [Google Scholar]

- Community knowledge and attitude to pulmonary tuberculosis in rural Edo state, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2013;12:148-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and practice about tuberculosis in India: A midline survey. New Delhi: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, South-East Asia Region; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with patient and health system delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in south India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:789-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditional knowledge on zootherapeutic uses by the Saharia tribe of Rajasthan, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:25. e1-6

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude towards tuberculosis among sandstone quarry workers in desert parts of Rajasthan. Indian J Tuberc. 2006;53:187-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn

- [Google Scholar]

- The health literacy of America's adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health literacy: An update of public health and medical literature. In: Comings JP, Garner B, Smith C, eds. Review of adult learning and literacy. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. p. :175-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-seeking behavior of new smear-positive TB patients under a DOTS programme in Tamil Nadu, India, 2003. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:161-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Care seeking behavior of chest symptomatics: A community based study done in south India after the implementation of the RNTCP. PLoS One. 2010;5:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude towards tuberculosis in a slum community of Delhi. J Commun Dis. 2002;34:203-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis knowledge, attitudes and health-seeking behaviour in rural Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:938-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and knowledge of newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients regarding the disease, and factors affecting treatment compliance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:300-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions and experiences of health care seeking and access to TB care - a qualititative study in rural Jiangsu Province, China. Health Policy. 2004;69:139-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longer delays in turberculosis diagnosis among women in Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:388-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Institute of Health Management Research (IIHMR). Accessibility and utilisation of RNTCP services by SC/ST population. Jaipur: IIHMR; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central TB Division. Baseline KAP study under RNTCP project. New Delhi: Central TB Division, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative assessment of KAP regarding tuberculosis and RNTCP among government and private practitioners in District Gwalior, India: an operational research. Indian J Tuberc. 2011;58:168-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central TB Division. A health communication strategy for RNTCP. New Delhi: Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005.

- [Google Scholar]