Translate this page into:

Molecular typing of Mycobacterium leprae strains from northern India using short tandem repeats

*Present address: Secretary (Department of Health Research) & Director-General, Indian Council of Medical Research, V. Ramalingaswami Bhawan, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India; e-mail: vishwamohan_katoch@yahoo.co.in & Former Director, National JALMA Institute for Leprosy & Other Mycobacterial Diseases (ICMR), Tajganj, Agra 282 001, India

Reprint requests: Dr V.M. Katoch, Secretary (Department of Health Research) & Director-General, Indian Council of Medical Research, V. Ramalingaswami Bhawan, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: vishwamohan_katoch@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Due to the inability to cultivate Mycobacterium leprae in vitro and most cases being paucibacillary, it has been difficult to apply classical genotyping methods to this organism. The objective of this study was therefore, to analyze the diversity among M. leprae strains from Uttar Pradesh, north India, by targeting ten short tandem repeats (STRs) as molecular markers.

Methods:

Ninety specimens including 20 biopsies and 70 slit scrappings were collected in TE buffer from leprosy patients, who attended the OPD of National JALMA Institute for Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, Tajganj, Agra, and from villages of Model Rural Health Research Unit (MRHRU) at Ghatampur, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. DNA was extracted from these specimens and ten STRs loci were amplified by using published and in-house designed primers. The copy numbers were determined by electrophoretic mobility as well as sequence analysis. Phylogenetic analysis was done on variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs) data sets using start software.

Results:

Diversity was observed in the cross-sectional survey of isolates obtained from 90 patients. Allelic index for different loci was found to vary from 0.7 to 0.8 except for rpoT for which allelic index was 0.186. Similarity in fingerprinting profiles observed in specimens from the cases from same house or nearby locations indicated a possible common source of infection. Such analysis was also found to be useful in discriminating the relapse from possible reinfection.

Interpretation & conclusions:

This study led to identification of STRs eliciting polymorphism in north Indian strains of M. leprae. The data suggest that these STRs can be used to study the sources and transmission chain in leprosy, which could be very important in monitoring of the disease dynamics in high endemic foci.

Keywords

Allele

M. leprae

molecular typing

phylogenetic

STRs

Leprosy, a chronic infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae, is one of the oldest recorded diseases of humankind. According to official reports received during 2008 from 118 countries and territories, the global registered prevalence of leprosy at the beginning of 2008 stood at 212,802 cases, while the number of new cases detected during 2007 was 254,525 (excluding the small number of cases in Europe). The number of new cases detected globally has fallen by 11,100 cases (4% decrease) during 2007 compared with 20061. In India, with the widespread use of multi-drug treatment (MDT) the elimination target has been achieved at the national level with a recorded prevalence of 0.83/10,000 population2. However, some pockets of endemicity still remain in certain areas3. Most of these remaining pockets of endemicity have been reported to be present in States of Bihar, parts of Uttar Pradesh, some parts of West Bengal, Jharkhand and Orissa45. This indicates the continued transmission of the disease in these areas.

The exact mode/mechanism of transmission of M. leprae is unknown. Since M. leprae cannot be cultured in vitro and it has a long as well as highly variable incubation period, it has been difficult to assess time of exposure, onset of infection and various aspects of disease progression.

During the last 20 years, several molecular assays have been developed for detection and analysis of M. leprae directly from patient specimens. These assays have been primarily based on the amplification of M. leprae specific sequences using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and identification of variation in the M. leprae DNA6. Several genotyping methods have been/are being developed and used for genotyping of M. leprae7–16. These techniques include targets, such as TTC78 rpoT9–12 and variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs)13–16. While initial studies had reported very high level of resemblance among M. leprae strains from different areas, subsequent use of new markers has provided usefulness in identifying strain differences. During the last several years following completion of M. leprae genome sequencing, the complexities of genome architecture has revealed a remarkable degree of structure variation present among different strains of M. leprae.

Molecular typing would not only be useful to study the global and geographical distribution of distinct clones of M. leprae, this would also provide some insight into historical and phylogenetic evolution of the bacillus15. This information would have potential application in studying transmission dynamics. Ultimate success of the strain typing by any of these targets can only be assessed after actual investigation(s) on strains in a given geographical area. In this study, the allelic diversity of M. leprae in 10 polymorphic loci short tandem repeats (STRs) was investigated in clinical specimens obtained from leprosy patients from geographically defined areas. Slit scrapings were also studied so as to evaluate the usefulness of this simple approach of collecting specimens that would be relevant for field applications.

Material & Methods

Collection of specimens : A total of 90 specimens – 70 slit scrapings and 20 biopsies positive for M. leprae specific PCR have been included in this study. These were obtained from leprosy patients who attended the Out Patient Department of Medical Unit- I of National JALMA Institute for Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, Tajganj, Agra, and Model Rural Health Research Unit at Ghatampur (MRHRU) at Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, during 2006-2007. Cases were diagnosed and classified by standard clinical criteria17. Among these 90 specimens, 26 slit scrapings were from paucibacillary (PB) cases and 44 slit scrapings and 20 biopsies were from multibacillary (MB) cases.

Isolation of DNA:DNA was isolated from frozen biopsy (weighing approximately 100 mg) as well as from slit scrapings by following a procedure described earlier18 as adapted by Sharma et al18. Bacilli were disrupted by freezing and thawing, followed by enzymatic disruption by lysozyme and proteinase K and deproteinization with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 v/v). After a brief centrifugation at 8000 g for 5 min, the upper phase was collected. DNA was then precipitated with 0.6 volume of isopropanol, washed with chilled ethanol and resuspended in 25 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer before being used for PCR amplification. PCR targeting RLEP gene region was performed to confirm the diagnosis of leprosy. Positive and negative controls were included in each set of experiment.

The blade used for routine smear purpose was put in sterile 400 μl of TE (pH 8.0) buffer. The material from the blade dissolved into a suspension in the TE buffer and this skin slit smear scraping suspension was used for molecular typing. DNA was extracted by similar method as for biopsies after their homogenization.

Construction of DNA Chip: A DNA Chip was developed for 37 loci targeting STRs predicted by Groathouse et al13. For PCR amplification, primers for some of the STRs were designed earlier91320, and for rest of the STRs primers were designed by us using online software Primer3 (www.fokker.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). STRs were amplified using these primers and the amplicons were used as spotting material to develop the DNA Chip. This DNA chip was used to screen the loci showing variability in two M. leprae strains (One reference strain and another obtained from clinical samples) by comparative genomic hybridization according to the protocol already standardized in our laboratory Cy 5 labelled DNA of standard strain Thai-53 and Cy3 labelled DNA of a lepromatous leprosy patient was used in the microarray experiments for identification of loci showing variability. The loci with a Cy5:Cy3 ratio of either >1.5 or less than <0.5 were included for further investigation for establishing the diversity.

While analyzing the diversity in 37 potential VNTRs by differences by hybridization on DNA chip, polymorphism was observed in 20 loci.

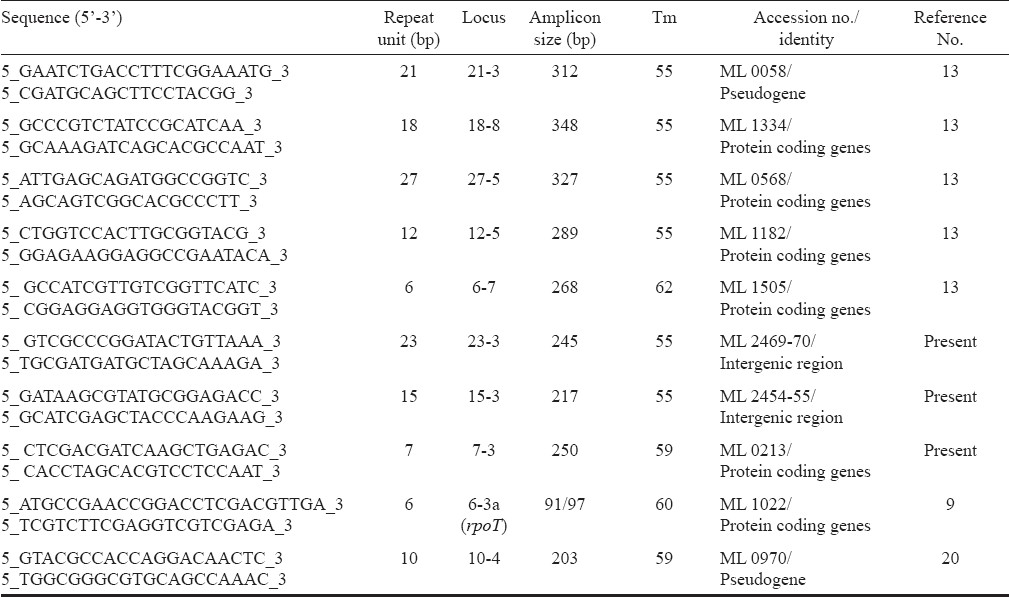

PCR amplification of STRs and sequencing: When D values were calculated with the help of Hunter Gaston Index21, nine loci showing significant variation were identified and included in the study. One locus ML2454-55 was also included to make a comparative analysis of variability of various loci in strains from different countries.

The sequences of primer pairs for these 10 loci are listed in Table I. A total 50 μl of reaction volume contained 5 μl of template DNA, 200nM of each primer (forward and reverse), 10 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs mix and 1.5U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, Banglore). Following the activation step at 95°C for 5 min, 10 cycles of touchdown PCR were performed in which the annealing temperature was reduced from 68 to 58°C at a rate of 1°C per cycle. After the touchdown phase, 25 additional cycles were run at an annealing temperature of 58°C followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. After PCR, the amplified fragment of the target region along with DNA ladder of 50 base pair, 25 μl of PCR product were electrophoresed in a 3 per cent agarose gel (Bangalore Genei, Bangalore) using tris acetate EDTA buffer (1X) at 50 volts constant current for approximately for 2 h. After electrophoresis DNA were further eluted from gel for sequencing.

PCR amplicons for sequencing were recovered from agarose gel by MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, GmbH, Germany) after electrophoresis of PCR products. Determination of sequences was performed using a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction Kit (ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer, Perkin Elmer, USA).

Analysis of genotypic data with respect to patients/ geographical distribution: Individual tandem repeats can be removed from or added to the VNTR via recombination or replication errors, leading to variants called VNTR allele with different numbers of repeats. Each variant acts as an inherited allele, allowing these to be used for personal or parental identification. In order to delineate relatedness among the north Indian strains, the VNTR data sets were subjected to phylogenetic analysis using the START (Sequence Type Analysis and Recombinational Tests, USA) software. In the START software UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) programme was used for analysis.

To assess the links between M. leprae strains and the likely source of infection to these leprosy patients, the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) to produce phylogenetic trees was used. The method uses a sequential clustering algorithm22. D (Discriminatory index) values were calculated with the help of Hunter Gaston Index21.

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Results

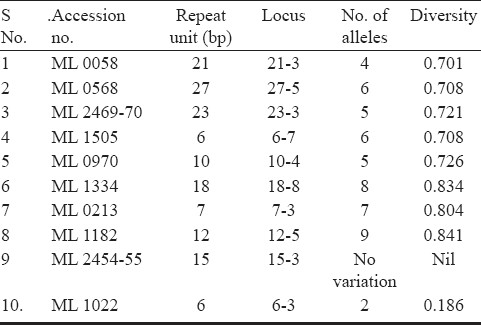

The allelic diversity of these loci among 90 north Indian patients is summarized in Table II. While gene targets from all these specimens could be amplified by PCR, smear positivity for acid fast bacilli was observed only in 27 of 64 (42.18%) of MB patients.

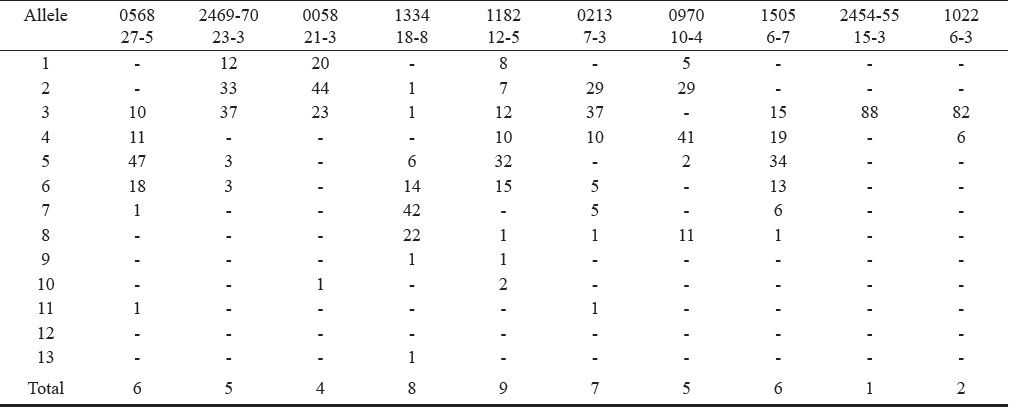

Strain diversity and population structure of M. leprae in northern India: The allelic index for each locus was found to range from 0.7 to 0.8 except for rpoT (ML 1022) for which the allelic index was 0.186 (Table II). Nine alleles were detected at the ML 1182 locus, ranging from those with copy numbers of 1 to those with copy numbers of 13 (Table III). In this study, it was possible to determine repeat copy numbers for all of the loci, even from biopsies which had been scored as polar tuberculoid and with no bacilli seen by microscopy. While one allele 15-3 did not show any variation, rpoT (ML 1022) had two alleles and the remaining eight had 4-9 alleles.

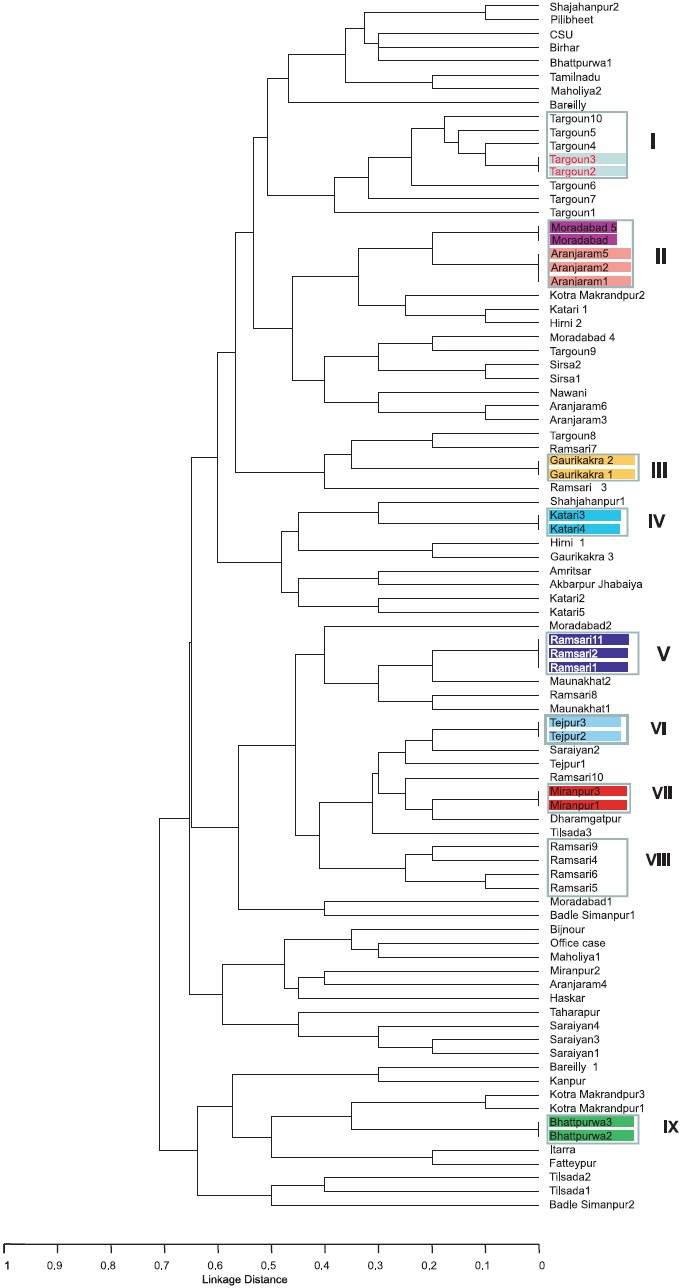

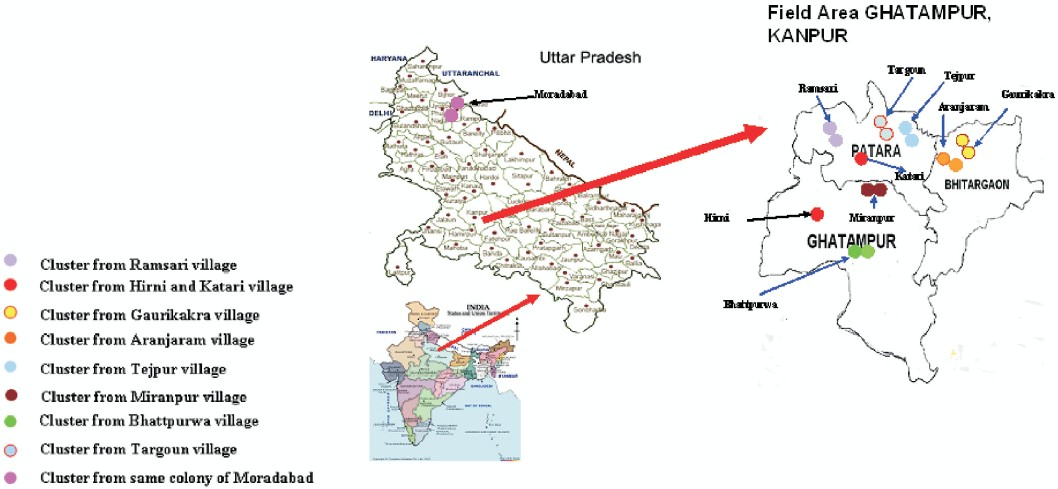

Phylogenetic analysis showed evidence of clustering associated with the geographical origin of the strain detected (Fig. 1). For example, village (i) Targaoun (ii) Aranjaram (iii) Gaurikakra (iv) Katari (v) Rathgoun (vi) Tejpur (vii) Miranpur (viii) Ramsari (ix) Bhattpurwa from the same village completely similar by STRs studied.

- Phylogenetic trees generated by the neighbour-joining method. Trees were obtained using all VNTRs.

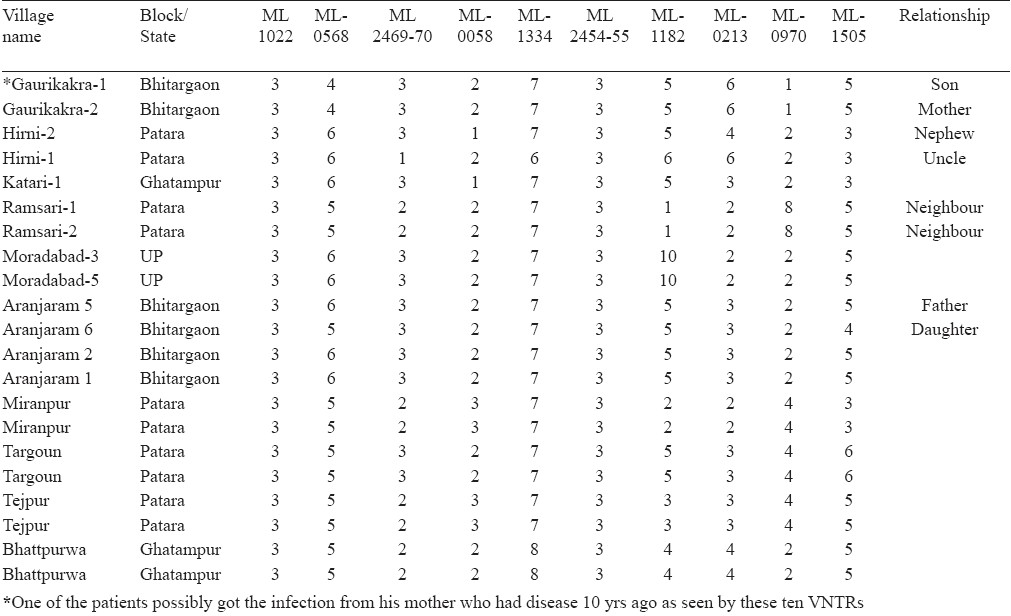

Genotype analysis in multicase families: From analysis of strains from villages of MRHRU at Ghatampur, intrafamilial transmission appeared to occur in some cases (Table IV). Matching alleles were detected at all ten loci, indicating a common source of infection and recent transmission within the household. By the use of combination of ten STRs clustering of strains from several defined geographical areas and villages was observed. It was observed that patients belonging to the same families (Table IV, Fig. 2) had similar strains as well as subtypes whereas others had different profiles. On the other hand, allelic differences across several loci seen within patient pairs (Hirni-1 and Hirni-2; Aranjaram-5 and 6) of families suggest that the family members harboured different strains indicating circulation of many strains in the community. It is interesting to note that Gaurikakra 1 and 2 were son and mother and infected with the same strain. Similarly, patients Hirni 1 and 2 who were also related (uncle and nephew) from the same village had same set of STRs.

- Distribution of clusters of M. lepraestrains from nothern India based on number of tandem repeats.

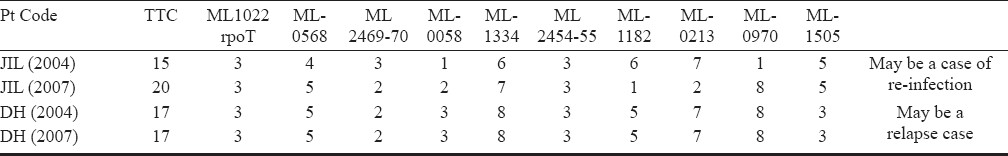

In this study relapse could be successfully differentiated from possible re-infection by using these STRs. The strain of the patient (name code: JIL) was different when he was first diagnosed in 2004, treated and released from therapy. On repeat examination in 2007, the bacilli isolated from his biopsies showed different number of TTC repeats (TTC is one of STR used initially for some of the strains in the study) and other STRs indicating re-infection with new strain. It may, therefore, be interpreted that this patient may have been re-infected with a different strain circulating in the community.

Another patient (name code: DH) was treated and subsequently released from treatment after completion of schedule. Later on after reappearance of clinical symptoms, the bacilli isolated from his biopsy showed bacilli with the same number of repeats thereby indicating a case of possible relapse with the persisting organism (Table V).

Discussion

Molecular typing of M. leprae presents several unique challenges and opportunities. The organism cannot be cultivated in vitro conditions and needs to be maintained by passaging in animals. Even among highly susceptible animal hosts, multiplication of M. leprae is quite slow, limited and requires several months to years to grow to a detectable bacterial mass. With such cumbersome maintenance requirements, there are relatively a few recognized M. leprae strains, and as a result very little is known about the adaptive traits or potential genetic alterations of M. leprae during long-term culture. Further, samples from leprosy patients can have many limitations. These are often of poor quality, the bacilli typically show a low per cent viability, these are frequently contaminated with other cultivable agents, and the cases may have uncertain treatment history. As M. leprae obtained through propagation in animals or derived from patient biopsies cannot be treated as a single colony, this may not represent a single clone of bacteria. In this study by focusing on STRs polymorphisms in M. leprae genome, meaningful diversity data have been generated. Only limited genetic polymorphism had been observed initially among M. leprae strains23–25. Cole et al6 presented an in silico analysis of M. leprae genome and showed that about 2 per cent of its chromosome consists of repetitive sequences. Such elements can be subjected to changes in size and sequence through random as well as evolutionary events and have been exploited as strain typing tools for other genetically homogeneous pathogens such as M. tuberculosis and M. bovis26–27.

Tandem repeats are usually classified among satellites, minisatellites and microsatellites. Both micro- and minisatellite loci have been investigated in this study to identify polymorphic loci as potential markers used as the tools for molecular typing of M. leprae. However, there are limited number of studies on the application of molecular tools to trace the sources and the possible chain of transmission1620252829. Our data showed that loci showing polymorphism could be different in different areas. While the loci 12-5, 21-3, 18-8, and 27-5 showed polymorphism, these were not found to be polymorphic in China25. Our data provided unique information about follow up of the cases, and relapse vs-re-infection by doing the repeat analysis on recrudence of the disease. Though the information may have greater local epidemiological application, this shows the potential of this technology to trace the sources, to address question of reinfection vs relapse and to create a larger database about the genotypes of M. leprae prevalent in India as well as all over the world, and also to the appropriate methods/loci needed to map these differences. For definitive conclusions, it would be appropriate to analyse several loci at the same time.

Clustering in strains from a family (mother and son seen in the present study) or nearby locations shows common source of infection or recent chain of transmission. While some of the strains from the same geographical area clustered, other from these geographical areas (villages) did not show such clustering suggesting circulation of different genotypes in a given area, a phenomenon commonly seen in high endemic settings when the people are exposed to different strains circulating in the community.

Analysis of these VNTR loci suggested a number of logical associations among M. leprae. The ability to link infections through bacterial genotypes raises the possibility, of using VNTRs in community-based studies on transmission of disease. However, some VNTRs appear to be hypervariable and may not be useful in either laboratory or field studies by using the Hunter Gaston Index. Others can be flanked or composed of sequences that may be problematic for reliable amplification. Certainly, little is yet known about regulation in the M. leprae genome or the influence of pseudogenes on VNTR mutation rates. Additionally, well-controlled studies with selected sets of patients or strains serially passaged in animals will be needed to describe the nature, frequency of these polymorphisms and their stability as molecular marker. The high degree of allelic diversity among M. leprae VNTRs imparts good discriminatory power for differentiating M. leprae strains. The data generated in this study suggest that genotyping has potential to become an effective tool to help monitoring drift and evolutionary changes within M. leprae strains. More in depth and prospective clinical as well as epidemiological studies need to be carried out using these loci in north India, the typing system may be useful in other settings also. Its ultimate application will require a better understanding of the biological diversity of M. leprae in different environments and cohort studies to determine linkages with actual occurrence of disease.

Authors thank ICMR (ICMR-Task Force Project No. 5/8/3(2)/2001-ECD-1), ICMR Leprosy Genomics Project (No.63/132/2001-BMS) for the financial support. Authors acknowledge the Field Staff (Shriyut Manoj, Anil Sagar, Santosh Bajpai, Kamal, Sanjay, Suresh, Mohan Pun, Vijay Pal, IA Siddiqui, Saurab, Akhilesh, Sunil, Raju and Rajendra) and other para medical staff of MRHRU, Ghatampur, for assisting in the sample collection, and thank Drs Gaurav Pratap Singh Jadaun and Pushpendra Singh for critical discussions and Shri Hari Shanker for technical help.

References

- World Health Organization. Leprosy Today. 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/lep/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- National Leprosy Eradication Programme. NLEP Data-Leprosy situation in India as on 1st April 2008. Available from: http://nlep.nic.in/data.html

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, country office for India. Leprosy situation in India epidemiological indicators. 2007. NLEP Indicators as on 31.06.2007 Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/EN/Section3/Section122_1461.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Pockets of high endemicity: Unfolding of the Ghatampur story. Indian J Lepr. 2005;77:343-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variable numbers of TTC repeats in Mycobacterium leprae DNA from leprosy patients and use in strain differentiation. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4535-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic polymorphism among Mycobacterium leprae strains from northern India, by using TTC repeats. Indian J Lepr. 2005;77:60-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycobacterium leprae typing by genomic diversity and global distribution of genotypes. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2000;68:121-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphism in the rpoT gene in Mycobacterium leprae isolates obtained from Latin American countries and its possible correlation with the spread of leprosy. FEMS Microbiol Letts. 2005;243:311-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotypic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae isolates from Japan and other Asian countries reveals a global transmission pattern of leprosy. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;261:150-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predominance of three copies of tandem repeats in rpoT gene of Mycobacterium leprae from Northern India. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:627-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple polymorphic loci for molecular typing of strains of Mycobacterium leprae. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1666-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotypic variation and stability of four variable- number tandem repeats and their suitability for discriminating strains of Mycobacterium leprae. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2558-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of short tandem repeat sequences to study Mycobacterium leprae in leprosy patients in Malawi and India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1987-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of sensitivity of probes targetting ribosomal RNA vs. DNA in leprosy cases. Indian J Med Microbiol. 1996;14:99-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diversity of potential short tandem repeats in Mycobacterium leprae and application for molecular typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5221-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sequence type analysis and recombinational test (START) Bioinformatics. 2001;17(Suppl 1):1230-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of the relatedness of Mycobacterium leprae isolates using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Acta Leprol. 1989;7:226-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Mycobacterium leprae genome: systematic sequence analysis identifies key catabolic enzymes, ATP-dependent transport systems and a novel polA locus associated with genomic variability. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:909-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification and distribution of Mycobacterium leprae genotypes in a region of high leprosy prevalence in China: a 3-year molecular epidemiological study. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1728-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology of disease due to Mycobacterium bovis in humans in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:431-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology. 1998;144:1189-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- A continuation: study and characterisation of Mycobacterium leprae short tandem repeat genotypes and transmission of leprosy in Cebu, Philippines. Lepr Rev. 2009;80:272-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population-based molecular epidemiology of leprosy in Cebu, Philippines. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2844-54.

- [Google Scholar]