Translate this page into:

Association between obstetric complications & previous pregnancy outcomes with current pregnancy outcomes in Uttar Pradesh, India

*Present address: Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, India

Reprint requests: Dr Deepti Singh, Doctoral Student, International Institute for Population Sciences Govandi Station Road, Deonar, Mumbai 400 088, India e-mail: dsingh.singh87@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

A substantial proportion of pregnant women in India are at the risk of serious obstetric complications and reliable information on obstetric morbidity is scanty, particularly in socio-economically disadvantaged society. We studied the association between the obstetric complications in women in their current pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in previous pregnancies in Uttar Pradesh, India.

Methods:

Data from District Level Household Survey (2007-2008) were used for empirical assessment. Bivariate, trivariate and Cox proportional hazard regression model analyses were applied to examine the effect of obstetric complications and previous pregnancy outcome on current pregnancy outcome among currently married women (age group 15-49 yr) in Uttar Pradesh, India.

Results:

The results of this study showed that the obstetric complications in the current pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in previous pregnancies were associated with the outcome of the current pregnancy. Cox proportional hazard regression model estimates revealed that the hazard ratio of having stillbirths were significantly higher among women with any obstetric complications compared to women with no obstetric complications. The adverse pregnancy outcome in a previous pregnancy was the largest risk factor for likelihood of developing similar type of adverse pregnancy outcome in the current pregnancy.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The findings provided key insights for health policy interventions in terms of prevention of obstetric complications to avoid the adverse pregnancy outcome in women.

Keywords

Association

current pregnancy outcome

obstetric complications

previous pregnancy outcome

There has been a significant decrease in the maternal mortality ratios (MMR) in developed countries during the twentieth century. However, developing countries still suffer from a large number of maternal deaths, and very often, pregnancy could be a risky event in a woman's life in these countries. Fifty per cent of the global maternal deaths occurred in the sub-Saharan Africa region alone, followed by South Asia, which contributed around 35 per cent; further, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia together account for 86 per cent of global maternal deaths12345. Globally, approximately 80 per cent of maternal deaths and 98 per cent of stillbirths have been due to direct obstetric complications, primarily haemorrhage, sepsis, complications of abortion, preeclampsia and eclampsia, and prolonged/obstructed labour6789. A substantial proportion of pregnant women in India have been at the risk of serious obstetric complications and most of them had been suffering from multiple complications101112.

Uttar Pradesh, a highly populous State in India with more than 170 million people continues to have the highest reported maternal mortality ratio in India13. According to Bhat14, the risk of death due to complications of pregnancy was highest in undivided Uttar Pradesh during the period 1982-1986 as well as during 1987-1996. Estimates based mostly on the sample registration system suggest that the maternal mortality in undivided Uttar Pradesh was the highest in the country in the year 1997 and was well above the national average14. Uttar Pradesh continued to be the State with higher maternal deaths; this indicates well above the national average of MMR of 407 per 100,000 live births15. Uttar Pradesh has also been the home for the highest number of women suffering from obstetric complications16.

Obstetric complications in the low-income settings have serious consequences both socially and medically1718. Obstetric complications have been used as a predictor of maternal deaths and other pregnancy outcomes. Threatened miscarriage, defined as vaginal bleeding before 24 wk of gestation, is a common complication affecting about 20 per cent of the pregnancies in India19. Pregnancy-related illnesses and complications during pregnancy and delivery are known to have a significant impact on the foetus, leading to poor pregnancy outcomes111920.

In India, reliable information on obstetric morbidity is scanty, particularly in socio-economically disadvantaged settings like in Uttar Pradesh, the effects of obstetric complications on the pregnancy outcomes have not been studied. Therefore, this study was an effort to find out the association between obstetric complications in the current pregnancy and the adverse pregnancy outcomes in previous pregnancies in women in Uttar Pradesh, India.

Material & Methods

The District Level Household Survey data (DLHS-3, 2007-2008)21 were used to explore the effect of obstetric complications on pregnancy outcome. A multi-stage stratified systematic sampling design was adopted for DLHS-3. In each district, 50 Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) which were census villages for rural areas and wards for urban areas, were selected in the first stage by systematic Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling. The Census of India 2001 was the sampling frame for DLHS-3.

Out of the sample of 7,20,320 households, 6,43,944 ever married women were interviewed and of these, 21,50,48 women were currently married in age group of 15-49 yr. In Uttar Pradesh, 82,194 currently married women were included as respondents. The study was restricted to only those women who had their last delivery after January 1, 2004. Hence, the final sample size of this study was 40,874 women.

Variables for the analysis: The following variables were considered in the analysis:

Outcome variables - Although maternal mortality has been widely considered as the key indicator of pregnancy outcome, maternal health, and human development, in the absence of accurate data on maternal deaths, the information on other pregnancy outcomes were used, such as stillbirth, or late foetal deaths, spontaneous abortions and induced abortions, which have also been considered reliable indicators of maternal health status6.

Predictor variables - Obstetric complications (refer to disruptions and disorders of pregnancy, labour and delivery, and the early neonatal period) such as swelling of hands, feet and face; excessive fatigue, convulsions, not from fever; excessive bleeding; vaginal discharge; pregnancy problem of weak or non moving foetus were used as predictor variables.

Other covariates: Cox proportional hazard models were used for important socio-economic characteristics which are associated with pregnancy outcomes: age of women, place of residence, caste, religion, education level of women, occupation of women, household economic status (wealth index).

Statistical analysis: All analyses were done using Stata 10.1 (Stata crop LP, USA) and followed two part analyses strategies: in the first part, bivariate and trivariate analyses were carried out. In the second part, the hazard ratios of stillbirths and spontaneous abortions were estimated by using Cox proportional hazard model2223 for those who suffered and those who did not suffer with obstetric complications. Further, in this model, the related socio-economic and demographic determinants were controlled to estimate the net effect of obstetric complications on the selected adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Results

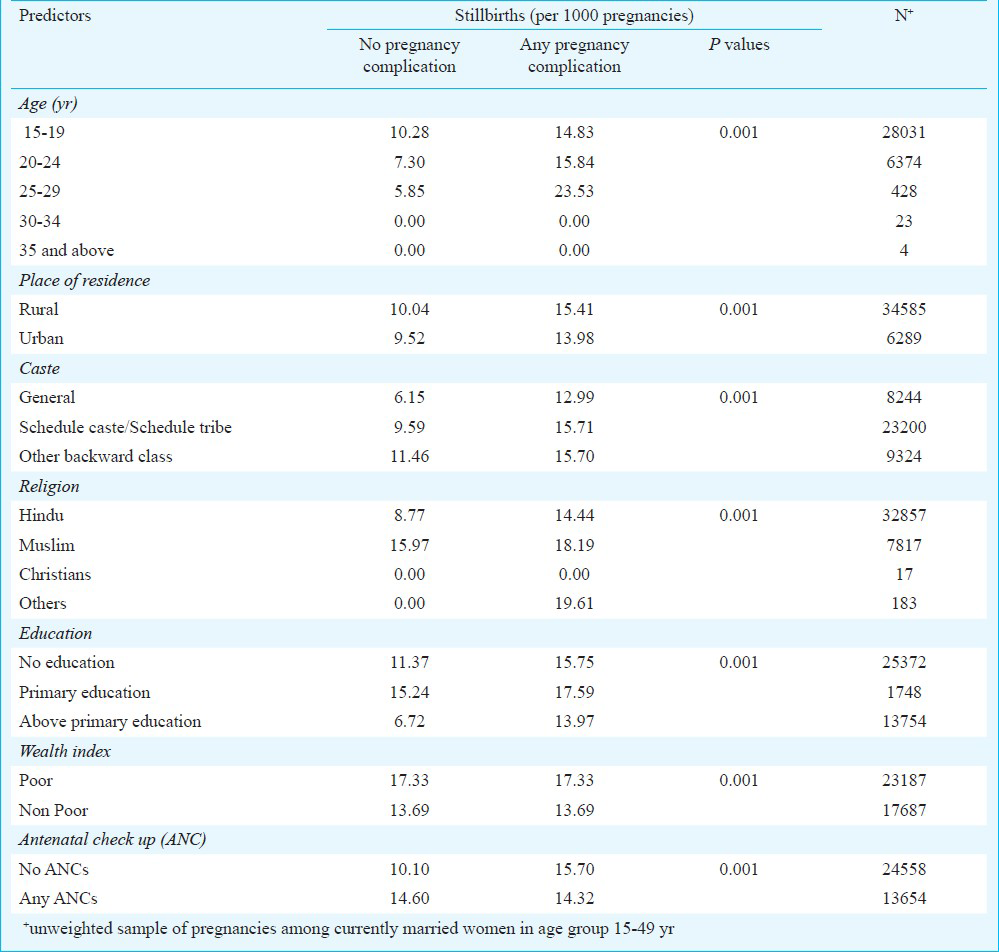

Prevalence of stillbirth by obstetric complication status: This study revealed that within the same socio-economic category, women who were suffering with any obstetric complications have faced greater adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to those who have not suffered with any obstetric complications. Table I presents the prevalence of stillbirths by the status of obstetric complications. For instance, among women in the age group 25-29 yr, stillbirths (per 1000 pregnancies) were five times more in women with any pregnancy complication compared to women with no pregnancy complications. Similarly, within the urban women, stillbirths for women with any obstetric complications (14 per 1000 pregnancies) were reasonably high compared with those women who had no obstetric complications (only 9.52 per 1000 pregnancies). Women belonging to Schedule Caste/Schedule Tribes (SC/ST) with any obstetric complications showed more stillbirths than other groups (Table I). The prevalence of stillbirth for women with any antenatal check-ups (ANCs) did not vary by pregnancy complication status.

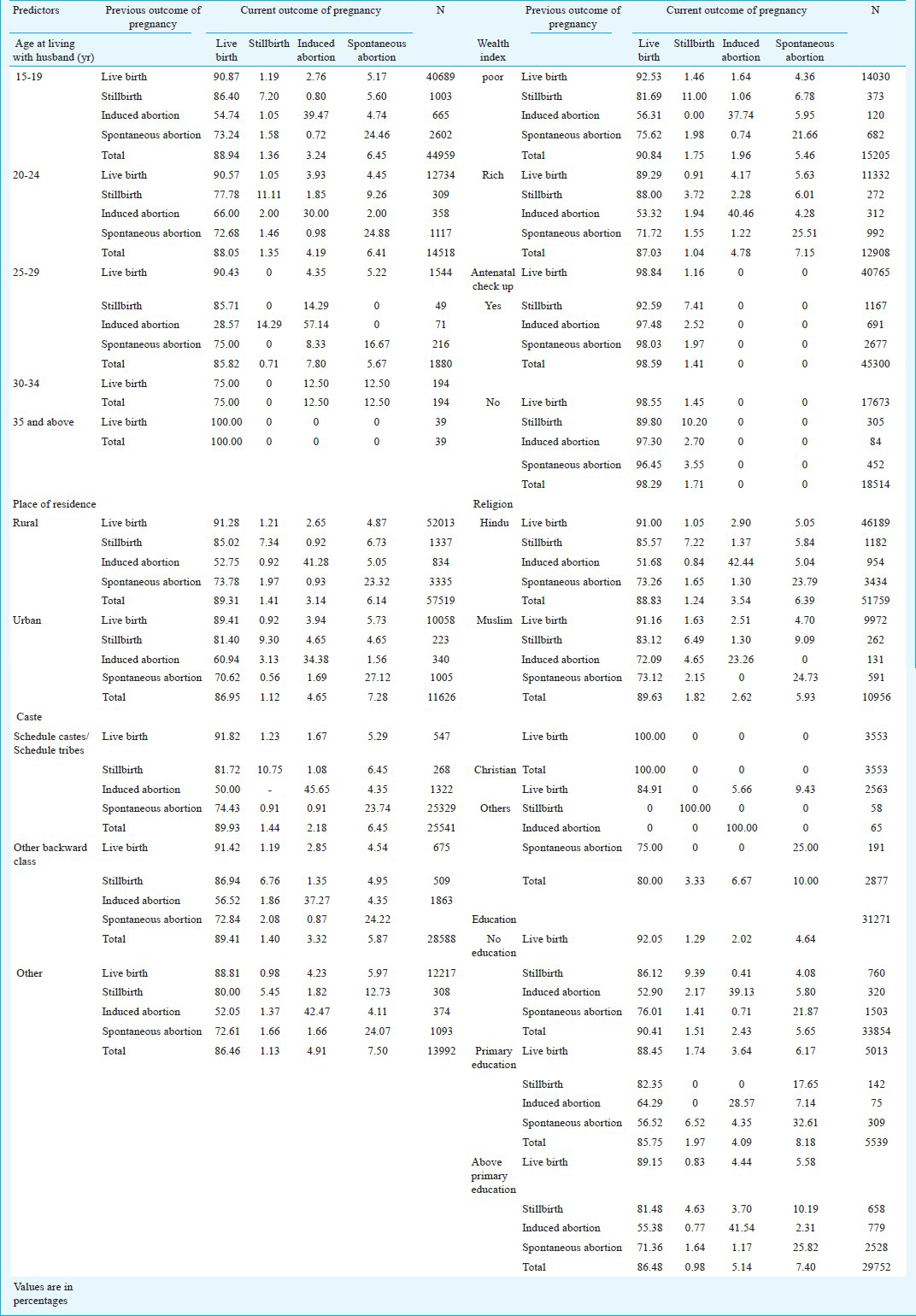

The results presented in Table II showed that among women of the same socio-economic status, a greater number of those who had an adverse pregnancy outcome previously had an adverse pregnancy outcome of their current pregnancy. Further, women who had experienced stillbirths previously also had stillbirth in their current pregnancy. Similarly, women who had experienced induced abortion and spontaneous abortions experienced similar pregnancy outcomes for their current pregnancy. For instance, among urban women, a greater proportion (9%) of those who experienced stillbirth previously had also experienced stillbirths in their current pregnancy. Among women belonged to rich household economic status, who had experienced induced abortion previously, 40 per cent of them had also experienced induced abortion in their current pregnancy.

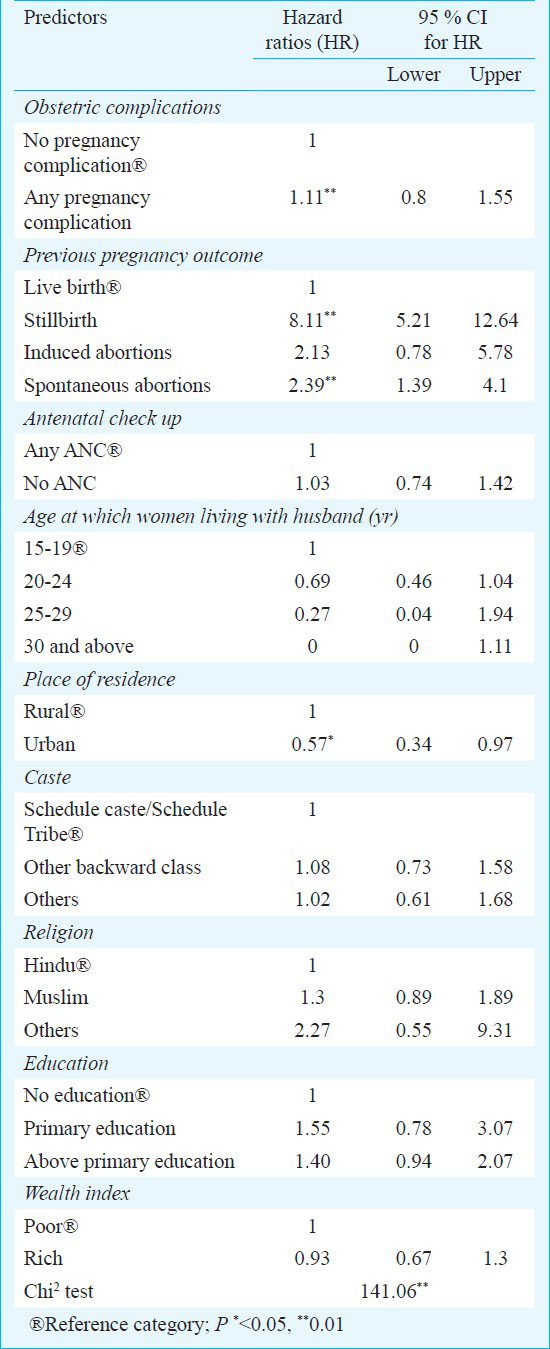

Hazard ratio (HR) estimates of adverse pregnancy outcome by obstetric complications and previous pregnancy outcome: The Cox proportional hazard model estimations in Table III were confound with the results of trivariate analysis. Among the same socio-economic and demographic characteristics, the hazard ratio of having stillbirth was greater among women who suffered with any pregnancy complication (HR = 1.11, P <0.01) compared to those who were not suffered (HR = 1). Similarly, prevalence of stillbirths was eight times more (HR = 8.11, P <0.01) for women who had stillbirths in the last pregnancy than women who had live births (HR = 1.00). The hazard ratio of having a stillbirth was also greater if a woman had a spontaneous abortion as a previous pregnancy outcome. The results indicated strong, positive association of stillbirths with obstetric complications and previous adverse pregnancy outcomes.

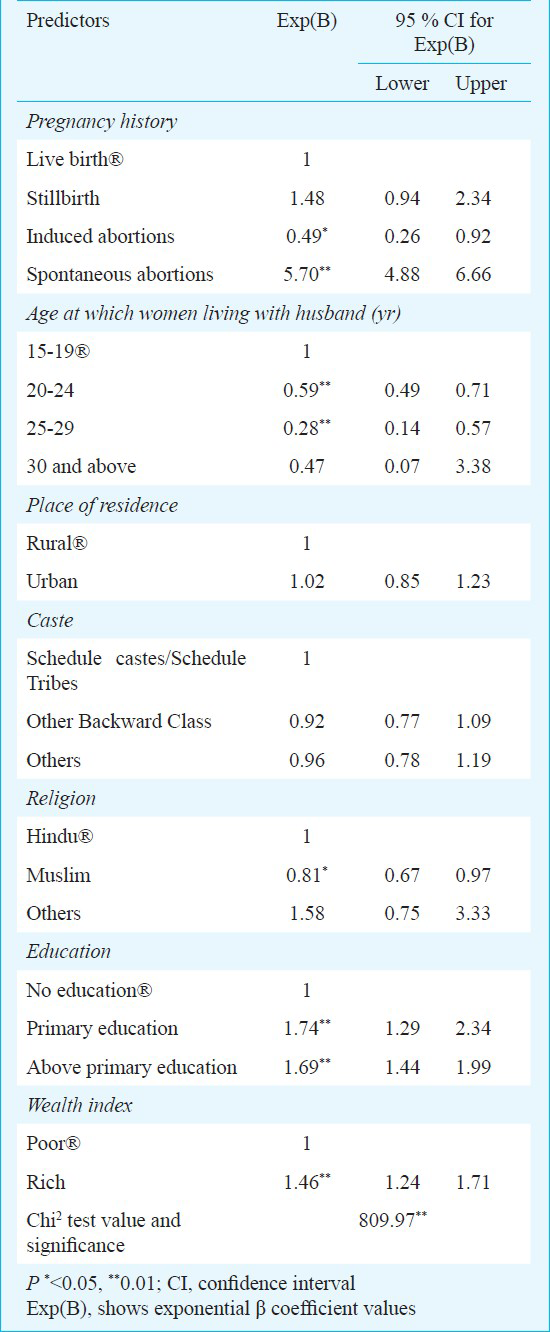

Table IV revealed that previous pregnancy outcomes had serious implications on spontaneous abortions in women in Uttar Pradesh. The previous pregnancy outcome such as spontaneous abortions and stillbirths showed strong and positive association with the current pregnancy outcome as spontaneous abortions. The hazard ratio of having a spontaneous abortion was six times (HR = 5.7, P <0.01) more among the women who had a spontaneous abortion in a previous pregnancy outcome than those who had a live birth as a previous pregnancy outcome (HR = 1.00). Similarly, prevalence of spontaneous abortions among women who had previous pregnancy outcome as stillbirths was also about twice (HR = 1.48, P <0.01) than their counter groups. Overall, Cox regression estimates suggest that the adverse pregnancy outcomes in previous pregnancies greatly determine the adverse pregnancy outcome of the current pregnancies compared to other background characteristics and spontaneous abortions as a current pregnancy.

Discussion

Studies conducted in India on the risk factors of maternal mortality and stillbirths101119 have not considered previous pregnancy outcomes as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes in the current pregnancy. The assessment of previous pregnancy history is very critical to avoid adverse pregnancy outcome in the current pregnancy. The key findings of this study were as follows: First, in Uttar Pradesh, a majority of women had experienced obstetric complications during pregnancy. The women in the younger age group and lower socio-economic status had experienced more number of stillbirths, induced abortions and spontaneous abortions compared to those with other age and high socio-economic status. Second, the results also demonstrated that among women with similar socio-economic status, obstetric complications emerged as the greater risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Third, after controlling for related socio-economic and demographic characteristics, the adverse pregnancy outcome in a previous pregnancy was the largest risk factor for the likelihood of getting similar type of adverse pregnancy outcomes in the current pregnancy. Though, some of the previous studies101119 documented obstetric complications as a risk factor of pregnancy outcome, but this study evidently supported it from the findings based on a large scale data. Moreover, this study documents the previous pregnancy outcome as a critical predictor of adverse pregnancy outcome in the current pregnancy.

The findings of this study provided certain important insights for health policy interventions in terms of prevention of obstetric complications to avoid adverse pregnancy outcomes. The knowledge of obstetric complications, adverse pregnancy outcomes, causes, and prevention feasibility are the key inputs to be given to women in India. Since, the same women face adverse pregnancy outcomes repeatedly, the targeted health policy intervention for women who had the pregnancy complication in their first pregnancy should be provided proper counselling and comprehensive health knowledge about obstetric complications so that they can seek proper medical care to avoid adverse pregnancy outcomes in future. The ideal mechanism is to provide health knowledge through lower level health workers. Strengthening of government health centers in terms of specialized services for gynaecological and obstetric complications at the local level is important to avoid unnecessary delay of the services and expenditures in impoverished families.

References

- Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375:1609-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank. Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tracking maternal mortality declines in Mongolia between 1992 and 2007: the importance of collaboration. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:192-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of women seeking medical care for obstetric fistula in Eritrea: implications for prevention, treatment, and social reintegration. Glob Public Health. 2007;2:64-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population Action International (PAI). How access to sexual and reproductive health service is key to the MDGs 2005; Fact Sheet 31 in series. Washington: Population Action International; 1985.

- [Google Scholar]

- House-to-house survey vs. snowball technique for capturing maternal deaths in India: a search for a cost-effective method. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:550-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for maternal mortality in Delhi slums: a community-based case-control study. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:517-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India. Provisional Results of Census-2011. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, Government of India; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of Registrar General. Sample Registration System (SRS), Statistical Report 2007. New Delhi: Office of Registrar General, 200; Government of India; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are self reported morbidities deceptive in measuring socio-economic inequalities. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:750-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro-Internationals. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3); 2005-06. Mumbai, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a prenatal yoga programme on the discomforts of pregnancy and maternal childbirth self-efficacy in Taiwan. Midwifery. 2010;26:e31-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demographic, socio-economic and medical factors affecting maternal mortality - An Indian experience. J Fam Welfare. 1993;39:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Registrar General, India. Maternal mortality in India: 1997-2003: trends, causes and risk factors. New Delhi: Registrar General, India; 2006. p. :1-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. District Level Household and Facilities Survey (DLHS-3) (2007-08): India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]